The 10 Beethoven indispensables

mainWelcome to the 125th final episode in the Slipped Disc/Idagio Beethoven Edition

In the course of the past half-year, I was often asked which are the most important works of Ludwig van Beethoven. It depends what you mean by important, and in which country you live. In Japan, they would certainly say the 9th symphony, which is a cherished December ritual. In the US, it’s more likely to be the Emperor concerto. In Germany, quite possibly the Pastoral symphony. In France and Britain, for different reasons, the fifth symphony. Such tastes are subject to cultural tradition and transmission, the question of what was played when an adult took you to your first Beethoven concert. As such, the answers given tend to be at least one generation behind the times.

If we judge by the measure of popularity, the last recordin industry figures tht I have seen show that the two top-selling Beethoven recordings of all time are Karajan’s 1962 ninth symphony and Carlos Kleiber’s fifth in 1975, both on DG and both surviving the test of time. But sales are not necessarily an arbiter of a recording’s historical importance. The top-selling Beethoven violin concerto features David Garrett with the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Ion Marin, not a performance that would make many critical shortlists, no matter how interesting the solist tries to make it.

A different arbiter of popularity is the Classic FM 2020 Hall of Fame, where Beethoven held five places in the top 20 with the 9th symphony, Emperor concerto, 7th symphony, Pastoral symphony and 5th symphony. This, however, would be largely a reflection of the station’s rather limited playlist. The Bachtrack annual survey of the works most performed in concert around the world puts, the fifth and seventh symphonies ahead of the Emperor concerto, the Eroica and the violin concerto. As you see, the same works crop up over and over.

Whenever I am approached for where to start in Beethoven, I ask myself first of all which works give me (a) most pleasure, (b) most cause for thought and (c) the greatest sense of discovery on repeated listening. It’s hard to narrow it down to just ten, but here’s what I have come up with. And if you want a guide to interpretations just click on each link.

1 Violin concerto, opus 61

An irresistible essay of ambition and passion, anger and rebellion. Once you start listening you cannot stop.

The odd-numbered symphonies get played more than the even numbers, but the seventh is not discussed as much as the rest. As daring as anything Beethoven ever wrote, it is a blaze of clashing emotions with barely a quiet moment to know what’s really going on.

The summit of the string quartet, nothing greater ever written.

There are 32 piano sonatas and you’d expect he’d be running out of things to say by the 30th. Not a bit of it: Beethoven grabs you by the lapel and starts a new conversation from which there is no escape.

Written for a visiting violinist of African extraction, the sonata signals Beethoven’s openness to people of all origins.

6 Piano concerto in G major, opus 58

While the Emperor concerto may win the popular vote, the preceding 4th concerto has the softest piano opening of any work in the rep and the most intellectual nourishment in its balance between individual and mass society. I’d rather hear this concerto than almost any other.

7 Judas Maccabaeus variations, WoO45

In his 20s, before he was famous, Beethoven doodled around with variations on great tunes by other composers. This set for cello and piano on a theme from Handel’s oratorio is fabulous and faultless. It’s a stepping stone to Beethoven’s brilliant solo-piano variations on his own Eroica theme and on another submitted by the publisher Diabelli.

The piano part has a particular poignancy: it was the last thing Beethoven ever played in public.

An incidental piece for a failed theatrical play, this is a display of Beethoven’s orchestral mastery condensed into 8 exhilarating minutes. It’s a work that separates good conductors from the very few great ones.

A work of seminal importance in European history and profound personal contemplation. Its funeral march features at some point in all of our lives.

There, it’s done. Or is it?

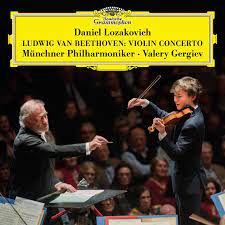

The new season’s relases are flooding in and, among them, two cracking Beethoven albums. Angela Hewitt’s set of piano variations on the Hyperion label (not yet on Idagio) is a compelling tour of the composer’s restless mind and agreeable conversation. And DG’s new release of the violin concerto with the teenaged Daniel Lozakovich (Munich Philharmonic/Valery Gergiev) has a commanding authority allied to a sweetness of tone that calls to mind the epic Fritz Kreisler of the 1920s and David Oistrakh of the 1950s. It’s the start of something new.

Comments