Why Hartmann is the composer of the moment

mainThe veteran director David Pountney is the force behind Independent Opera’s staging next week of the UK première of Karl Amadeus Hartmann’s Simplicius Simplicissimus, at the Lilian Baylis Studio, Sadler’s Wells.

David, the opera’s translator, is director of Welsh National Opera. But he is passionate about restoring forgotten composers, such as Mieczyslaw Weinberg, Andre Tchaikovsky and Hartmann. As I have explained elsewhere, Hartmann was the only established composer in Germany who actively resisted the Nazi regime.

In this article, written for Slipped Disc, David Pountney explains why Hartmann needs to be heard – and now.

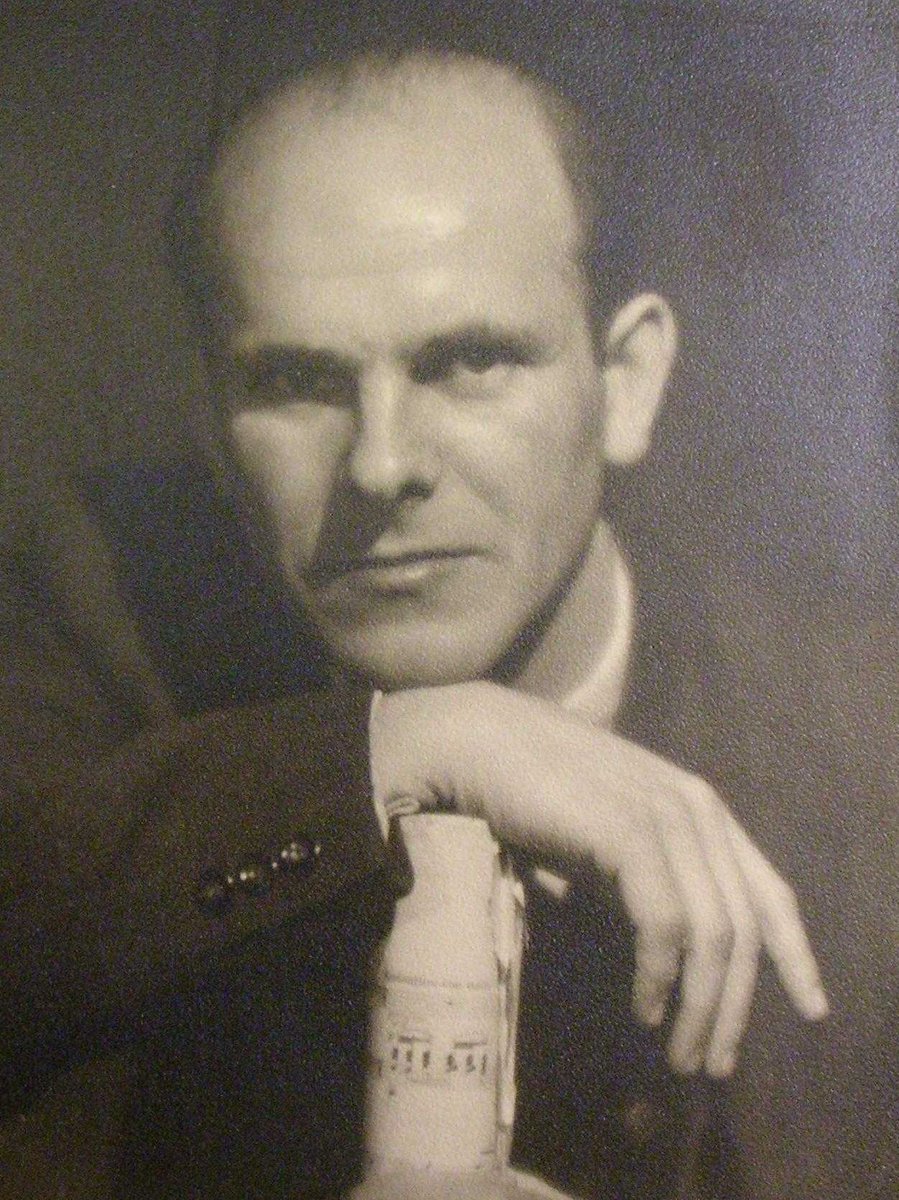

Karl Amadeus Hartmann was born in Munich in 1905 into a bohemian family of painters. Unlike his brothers and sister who became painters in turn, he turned towards music, eventually becoming a trombonist in the Munich Opera orchestra. In 1918 he witnessed the Bavarian workers revolt which broke out at the end of World War One and seemed for a time as if it might establish Bavaria as a separate, radical workers republic – a very curious thought now! The politics of this uprising were a lasting influence on Hartmann who continued to hold partly disguised Marxist views for the rest of his life.

“Disguise” is a salient word however, as his participation in the Jazz influenced world of Weimar music came abruptly to an enforced halt with the election of the National Socialists in 1933. From this point on Hartmann became a prime exponent of what was later termed “inner immigration”. How did this work?

He was careful neither to seek nor accept any commissions from the Reichsmusikkammer even though this body (under its President Richard Strauss!) continually demanded that he present proofs of his Aryan identity, and he studiously avoided performances of his works in the Third Reich, being able to rely on financial support from his wife’s family. Instead he focused on achieving performances abroad with some success, which calls for a little care in considering his “arms length” status in regard to the Reichsmusikkammer. He would not have been allowed to travel abroad without that body’s tacit approval, so he was by default a member though refusing any act of participation. None of us who have not experienced totalitarian rule should ever judge the means by which people managed their lives under these impossible circumstances, but nonetheless a degree of nuance suggests that we should not exaggerate heroism or be too quick to denounce small compromises.

In artistic terms “inner immigration” manifested itself in very subtle, sometimes almost unreadable artistic signs embodied in his works, a technique described as “verdeckte schreibweise” (concealed ways of writing). Music, in this case, becomes a language to be de-coded, and as soon as we embark on this theme you will instantly recall the case of Shostakovich for whom this was also an essential but highly complex necessity. Simplicius contains many examples of this technique.

Firstly the theme itself of an Ur-Deutsch story going back to the peasants revolt (adulated by the Nazis) and the 30 Years War shows Hartmann “repatriating” a fundamental item of German cultural heritage and using it for anti war, anti-heroic, and hence for silently anti-fascist purposes. Then he incorporates into the music of Simplicius themes that represent forbidden musical cultures, thereby repatriating these too. In the overture there is a Jewish melody on the violas, “Eliahu ha-navi”, which he also uses even more explicitly in his second quartet of 1933.

Alongside this Jewish reference, at the end of the opera when the peasants are becoming radicalised, he uses a march theme from a Prokofiev piano work as if to invoke Soviet musical style, and furthermore includes a version of the traditional peasant protest song “Wir sind Geyer’s Schwarzer Haufen” which had in the meantime been mis-appropriated by the Nazis, and deliberately uses passages of “speech choir” which was a technique much used by “approved” Nazi composers.

Secrecy in music was of course an aspect of musical fashion not solely dependent on totalitarian supervision. Alban Berg’s fascination with numerological codes led him to incorporate hidden messages in his music, as did Shostakovich. The 5th symphony, for instance, can be read as a searing parody of Soviet bombast, but just as you have satisfied yourself with this interpretation, it emerges that it also conceals quotations from Carmen which refer to a secret girl-friend. This reminds us that music is a hermetic language, and it may be reasonably questioned whether Hartmann’s secret protests incorporated into his Simplicius score could possibly be understood by anyone other than him. That is possibly the true meaning of inner immigration or “aesthetic resistance” as it is sometimes called: this is a secret dialogue with himself.

After the war, Hartmann was one of the very few surviving musicians still in Germany untainted by direct association with the Nazis, and was appointed dramaturg of the Bavarian State Opera. In addition, he was generously patronised by the Americans, keen to re-establish German culture and hence, political stability. Hartmann carefully airbrushed out his Marxist past, and in return the Americans generously helped him to found his extremely influential Musica Viva series which was generous in repatriating many of the composers stamped out by the Nazis, as well as giving ample opportunities to younger talents like Hans Werner Henze. Hartmann’s subtle and intelligent ability to move with the wind enabled him to achieve significant cultural advances, and his open spirit re-invigorated post war musical life in Germany.

Simplicius is in some ways at odds with this cultivated and sophisticated approach. The original story, a masterpiece from the 17th century, reflects a brutal history of violence unequalled in Europe until the catastrophic but brief Fascist era. (In between, Europe had exported its violent tendencies to its colonies!) This relentless horror is ironically seen though the eyes of a helpless innocent, through whom it is visible in all its naked fury. The humane and compassionate Hartmann here finds a voice through whom he can speak about the evils of war with unrestrained loathing and abhorrence.

(c) David Pountney

Great initiative and good news that H’s opera is revived. But let us have a look into the background and the underlying humus.

It seems obvious that the reason that Hartmann as the only German composer resisted nazi affiliations, was because he could afford it: there is not much heroism in withdrawel to your villa in the countryside, stop your career and write for the drawer untill the clouds have lifted.

“The worst is that German music as an art was a willing instrument of the Holocaust and would bear the consequences of its complicity for all eternity were it not for the noble exception of one fine man, just one – Karl Amadeus Hartmann.” (NL in his article on La Scena Musicale). I think that goes much too far: music was not ‘an instrument of the Holocaust’, and what about German music of pre-nazi times? And what about Schoenberg, Berg, Hindemith, and – yes – Strauss, who paid dearly for his silly opportunism and naivety? (Webern, who supported nazism enthusiastically all the way through the war and inspired postwar sonic art, better be left out.) One should not forget that not only Strauss, but also Hindemith and Adorno were very enthusiastic nazi supporters in the early thirties, only to find-out later-on when they bumped into personal barriers that they had gambled on the wrong horse. Later-on they became symbols of anti-nazistas but obviously, it had taken some time. And Darmstadt just after WW II was led by ex-nazis, who had quickly and easily turned their coat when anti-nazi modernism became ‘de rigeur’ at that ideologically-perverted place… they had to be weeded-out when such roots in the past became an embarrassment. But the transition from nazi-approved music to postwar modernism was apparently very easy, and of course it was.

But that does not mean that this German luxury composer was not talented: much of Hartmann’s music is not only brilliant, but should be part of the repertoire, like Shostakovich’s, and not because he wrote ‘against the nazis’, but because of the qualities. Hartmann wrote the music that Schoenberg could have written had he not invented that silly 12-tone system:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=N3pC5LMXqyE

A quasi-Schoenbergian work full of invention, expression and fantasy – but also ful of dissonance, which gets rather tiring on the ear, but which the listener gets used to and will embrace wholeheartedly if listened after Xenakis, Stockhausen or Boulez. Interestingly, the dissonances are harmonically meaningful and, in fact, entirely tonal.

Of course the traditional basis of H’s work, with even some ‘academic’ streaks here & there, made him ‘irrelevant’ for postwar ‘new developments’. But it is much to his credit that his work could not lead to sonic art, but remained real music, as an expressive art, albeit with dark hues most of the time.

H’s Concert Funèbre is another brilliant and moving work in a beautiful harmonic language.

A shame that his music had fallen aside the ‘road’. That Karajan and Böhm did not like his music, was probably because the sheer sound of most of it is not ‘beautiful’ and not ‘audience friendly’, and because of H advocating Schoenberg et al in his Munich series which formed the humus upon which German modernism: the enemy of the central performance culture where these conductors were operating. Karajan and Böhm must have been profoundly embarrassed by their brown associations, and tried to completely ignore the past, so the last thing they would have liked to promote was Hartmann’s work which would rub it in quite drastically.

It is to be hoped that Hartmann will take his deserved place in 20C music history, like so many other composers who were sidelined by the postwar neo-fascistic ideology.

Hartmann was a truly fine composer who wrote some of the best symphonic works of the 20th century. His works should be much more known, especially the symphonies. However, much what you wrote is complete nonsense. Neither Hindemith nor Adorno were ‘enthusiastic Nazi supporters’. Maybe you ignore that both went into exile early on? Regarding Darmstadt: Steinecke, one of the founders of the institution may have been a Nazi but you can’t certainly say this of those people who gave the first courses there: Scherchen, Leibowitz, Krenek, Varese, Kolisch, Adorno etc. By no means I can see how they did ‘ideologically pervert’ the place.

According to your logic, anything in postwar art that is not approved or understood by you must have its roots in Nazi barbarism. Not to mention that all these open-minded composers you don’t like generally had no talent at all.

From ‘The Classical Revolution’, Scarecrow Press / Rowman & Littlefield Publishers 2013:

As can be read in Karen Painter’s thorough study: Symphonic Aspirations, German Music and Politics 1900 – 1945, to see art music as imbued with political messages was, for both musicians and composers, normal in that period of politization of all strata of society. Webern sympathized with the Nazi ideology at a time when it was already quite obvious in which direction the new regime in Germany was heading, assuming that his music would undoubtedly be the perfect music for the Third Reich and getting really surprised when his music fell upon the government’s deaf ears – since the nazi leaders had decided that Beethoven and Wagner were much better composers to demonstrate German cultural superiority. But Webern’s expectations are fully understandable: it is not difficult to see a link, in terms of mentality, between the totalitarian nature of the dodecaphonic system and fascist ideas of equality, militarism and top-down discipline. Also some musical intellectuals, including some of Jewish background, initially felt great sympathy for the ‘new Germany’. In a review in 1934, a year after Hitler’s spectacular coup, Theodor Adorno – whose influential Philosophy of New Music provided the musico-political ammunition after 1950 to support the claims of atonal modernism – invoked Joseph Goebbels in his (Adorno’s) recommendation of some choral publications, obviously in sympathy with a regime that had already shown its teeth. Here, there is not much difference with the naive and misconceived optimism of Richard Strauss and Paul Hindemith who both believed that the new Germany would make necessary reforms in music life possible. Heinrich Strobel, after 1945 music director of a German radio station and the Donaueschingen Festival, another important advocate of modernism who has done a lot for the postwar Darmstadt avant-garde, recommended Goebbels’ ‘steel-like romanticism’ when reporting on the German Composers Festival in 1933, shortly after assuming the editorship of the new-music journal Melos. This happened after the former editor was ousted for ‘political unreliability’. (Strobel even remained editor after the journal was nazified and renamed Neues Musikblatt.) Ironically, both Adorno and Strobel sympathized with a political climate which forced them both into emigration (Adorno, and Strobel’s wife, were Jewish).

In Toby Thacker’s Music after Hitler, 1945-1955, we read that the composers Wolfgang Fortner and Hermann Heiss, who were involved in the setting-up of the Darmstadt Summer School after the war, were both blacklisted by the American occupation army. Heiss had happily collaborated with the Nazi regime with writing marches, as Fortner had specialized in ‘festive music’ for the Hitler Jugend and had conducted the Hitler Jugend Orchestra in Heidelberg. The transition from totalitarian state service to modernist musical paradigms obviously was not a very difficult one. As Thacker describes:

“Heiss was the first in post-war Germany to write extensively about twelve-tone music. At Darmstadt in 1946, he declared: ‘We have today a unique opportunity, with our experience and knowledge, to preserve young people from wrong turnings and detours’. […] Fortner also turned rapidly to twelve-tone music. Alongside Heiss and Fortner, many of the composers whose music was played at Darmstadt in 1946 were compromised, such as Degen, Pepping, Distler, and Höffer. The piano class was taken in 1946 and 1947 by former NSDAP member Udo Dammert, who was certainly persona non grata with the Americans, having falsified his ‘Fragebogen’ (questionnaire).”

The Darmstadt Summer Course, which became the ideological centre of modernism in the postwar years, was set-up as a symbol of cultural freedom and as such it was treated as propaganda, as is shown by the involvement of the American Military Government and Radio Frankfurt. Also the postwar continuation of the festival of Donaueschingen, which under the Nazis had been turned into a celebration of Germanic festive and folk music, was supposed to be a sign of a return to normality in a free world, although its first postwar director, the composer Hugo Herrmann, had in earlier years conducted the National Socialist Symphony Orchestra there, in a brown dinner jacket. ‘The German composers whose works were played, von Knorr, Gerster, Degen, Hermann himself, were all compromised’ (Thacker). In 1950 a new format of the festival corrected this all-too-easy change from one context to another, and became more ‘acceptable’, quickly developing into an international showcase for atonal modernism, which had been condemned by the Nazis as entartet (corrupted) and imbued with ‘Jewish influence’.

————————————

Second, paperback edition by Dover Publications in preparation.