How Beethoven arrived at the ninth symphony

mainWelcome to the 108th work in the Slipped Disc/Idagio Beethoven Edition

Symphony No. 9 in D minor op. 125

It is not the end. It is not even the beginning of the end for Ludwig van Beethoven, who has another dozen scores in him before death comes calling at the age of 56. He is not thinking about death. Nowhere does he mention the ninth symphony as a final testament. He has more to say, more to achieve, but in the years that he devotes to the ninth symphony he is forced to recognise that there is no point in him writing anything more for the symphony orchestra. It is the loudest instrument on earth and he is too deaf to hear it.

So this is a turning point, and an important one. If he can no longer hear an orchestra, he need not worry about what anyone, starting with musicians, think about his music. After the Ninth, he listens only to an inner voice and writes strictly for himself. His ultimate medium is the string quartet, four players in a tight circle who cannot let each other down. The 9th symphony will be Beethoven’s farewell to the public arena of the concert hall, his final retreat to the inner chamber of his hyperactive mind.

Twelve years have elasped since his last symphony, the defiantly frivolous 8th of 1812. There have been stops and starts. Sketches of the opening of the 9th appear in his notebook in 1817. A year later he appears to be writing two symphonies at once. In 1819 he is distracted by family affairs and writing the last 3 piano sonatas and the Missa Solemnis. In December 1822 he accepts a commission for the ninth symphony from the Philharmonic Society in London, a city he has never seen. He does not warn the English that the symphony has a choral finale, sung in German, because he does not yet have any idea how the work will end.

A thought has been nagging for years at the corner of his mind. In 1793, a friend reports that Beethoven wants to set Schiller’s ‘Freude’ to music (Friedrich Schiller’s ode to brotherhood first appeared in print in 1786). In 1811, he transcribes Schiller’s opening line into a notebook and reminds himself to ‘work out the overture’ for it. Later in the notebooks there is mention of ‘the Schiller overture’. In so far as we can follow Beethoven’s processes, he lets flotsam and fragments float around his mind until all fall into place.

The symphony takes up most of 1823. He struggles to get the first movement going. By the end of August he has about 15 minutes of music, but no clear path ahead. The serene Adagio takes him two more months. Finally, after taking another of his rest cures in Baden, he returns to Vienna with a sketchbook in hand, shouting, ‘I have it! I have it.’ The symphony is complete and he has written a finale which requires the additional forces of a mixed chorus and four vocal soloists: bass, tenor, soprano and alto.

The finale is not a total surprise. Beethoven had involved a chorus in the quasi-concerto that is the Choral Fantasia and was still very much in the sound world of the Missa Solemnis. The shock of the finale lies not so much in its originality as in its unexpectedness. In three preceding movements Beethoven takes us on a tour of all the developments has made to symphonic form. It is a leisurely journey, taing all of three quarters of an hour, longer than any symphony ever written before, and when he comes to the finale Beethoven is still in no hurry.

For six minutes, the orchestra continues in much the same reflective mood as before. Then, uprompted, with a spurt of pace and a shout from the bass singer ‘Oh, friends, not these tones’, everything changes. It is the single most transformational moment in musical history. Once this cry has been heard, there is no turning back to the servility of Haydn and Mozart. Music has claimed the right to change the world. It has the power of social confrontation and the potential to improve human life. It has taken leave of the tones that went before. Those words ‘not these tones’ are writen by Beethoven, not Schiller. He has broken with the past.

At the start of January 1824, he has an attack of human kindness and sends new year’s greetings to his brother’s widow Johanna whom he has been fighting for years through the courts. Perhaps the Ninth is making him a nicer man? Rich Viennese friends book the Theater an der Wien orchestra, the best in Vienna, for the premiere. Beethoven, despite his deafness, insists on conducting the performance. Maybe just the overture? friends suggest. No, says Beethoven: the whole concert. Rehearsals are fraught. The concert announcement says that ‘Herr Ludwig van Beethoven will himself participate in the direction’. He is unsure, up to the last minute, whether the censor will permit the performance.

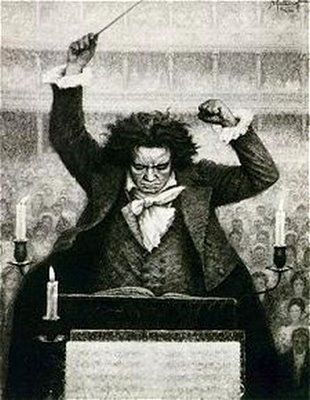

At seven in the evening of May 7, 1824, Beethoven mounts the rostrum of the Theater am Kärntnertor. He is wearing a green coat because he does not own a black one. The royal family are out of town, along with much of the nobility. But musicians and the middle classes surge to the hall, aware of the momentousness of a new Beethoven symphony. Some are borne from their deathbeds on stretchers. It is truly a once-in-a-lifetime occasion. The violinist Joseph Böhm writes: ‘Beethoven himself conducted – that is, he stood in front of a conductor’s stand and threw himself back and forth like a madman. One moment he stretched to his full height, at the next he crouched down to the floor, he flailed about with his hands and feet as though he wanted to play all the instruments and sing all the chorus parts.’

The second movement is interrupted by wild applause. Beethoven is oblivious. At the end, the soprano plucks his sleeve and points to the clapping, cheering, foot-stamping audience. ‘My triumph is now attained,’ replies Beethoven, but the concdert loes money and a repeat performance 16 days later loses even more. He accuses friends of cheating him and writes to several publishers, trying to sell them rights in future works. Any happiness he derives from the triumph has dissolved.

It is important to appreciate the circumstances of the 9th’s creation, to grasp the misery of its creator. He is in contant pain, short of money, fearing betrayal by those closest to him, cut off from them by his now-total deafness. To conduct the Ninth without staring into these depths amounts to a travesty of its conception. There are many performances on record which barely touch the surface. Before I examine the entire recorded archive in the next couple of posts, here are two which plumb the depths.

The conductor Felix Weingartner, who knew Brahms and Wagner, recorded Beethoven’s 9th in 1935 as an informed synthesis of both streams of tradition. It is a cornerstone of recording history. Listen here.

Jascha Horenstein, who fled Nazi Germany and lived in relative poverty in the US and Britain, made a recording of the ninth in Vienna in 1956, using players from the Vienna Philharmonic under a fake name and soloists of the highest calibre. This, too, earns its place on any extended shortlist. Horenstein was a modernist, always looking ahead to the next musical evolution. Listen here.

To be continued tomorrow.

Comments