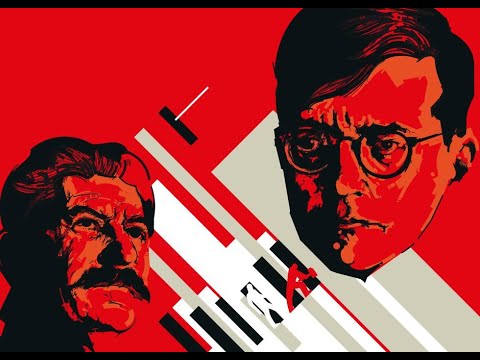

Everything you ever wanted to ask about Shostakovich and Stalin

mainThe Fortnightly Book Club resumes today. Here’s moderator Anthea Kreston:

Shostakovich – the man, the music, the world he inhabited. These are the themes investigated in this series of Fortnightly Music Book Club. Our selected materials – three books and one cd – are merely jumping-off points for our imaginations. Let’s travel back in time, and find a path through the complex, devastating and wondrous world of Shostakovich.

Answering questions this week are Elisabeth Wilson (author), and Elisabeth von Leliwa (musicologist and vice-president of the German Shostakovich Society). We at Slipped Disc are honored that they have agreed to join us on this journey.

Materials read/listened to:

Julian Barnes: The Noise of Time

Elisabeth Wilson: Shostakovich, A Life Remembered

Solomon Volkov: Testimony

Artemis Quartet: Shostakovich (Erato)

Questions can be left below in comments, or sent to Fortnightlymusicbookclub@com.

Reader Question:

How was Shostakovich able to escape the fate that many of his friends and colleagues suffered? Solomon Volkov has a theory that Shostakovich was seen as a “yurodivy” – a Russian religious figure who has the ability to see the truth, expose injustice, and to convey it through crude methods. In this way, he was protected because of his gift. What is your opinion?

Elisabeth Von Leliwa:

Personally, I don’t care for Volkov’s “Yurodivy” theory. Yurodivy translates roughly into “God’s fool“ and describes a person who acts foolishly, very often bordering on the “insane“. The most famous examples in Russian literature are the Fool in Pushkin’s and Mussorgsky’s “Boris Godunov“ and Prince Myshkin in Dostoyevsky’s “Idiot“. Shostakovich, with all his intellectual powers, could hardly count as a “fool“ and certainly wasn’t seen as one. It is also rather obvious that Stalin or his minions have not been able to detect the “truths“ hidden in Shostakovich’s music.

In my opinion, the reason for Shostkovich’s survival lies in Stalin’s personality – and the way dictatorships work all around the world: based on terror and complete insecurity. Persecution needs no logic, on the contrary. Stalin delighted in the power of letting a person live – or not. There is no explanation for Shostakovich’s – or for example Boris Pasternak’s or Maria Yudina’s – survival, but the whims of the dictator. This dependence on irrational, individual decisions even reinforced the terror of Stalin’s regime and power.

Reader Question:

How did writing your book, Shostakovich, a Life Remembered, change your opinion of Shostakovich as a human?

Elisabeth Wilson:

Writing my book naturally took me nearer to Shostakovich’s music and to a deeper understanding of how to approach it. I already knew of Stalin’s terror and the arrests and gulags, etc. and the difficult life ordinary people led. And the special problems of being an artist in Soviet society. What impressed me most was how people had to go on living their “ordinary” lives even in these times of terror. Shostakovich had an impressive inner dignity and wisdom which I came to respect more and more. In Soviet times to say somebody was “decent” was the greatest compliment. He might be frightened, he might not have great courage, but he would never cause harm to others by “reporting” or by saying the wrong thing in the wrong company, and would help people discreetly without advertising his actions. Shostakovich was just such a “decent” person, even if later in his life he accepted compromises by, for instance, not stopping his name being put as a signatory on some official article published in Pravda.

Shostakovitch joined the Communist party in the 1960´s. That´s how he survived.

Yes – what a difficult choice that was for him. But he had already been dodging the bullet for quite some time before that – many of his friends didn’t live to see the 60‘s. It’s an incredible journey that he took.

[[ Shostakovich, with all his intellectual powers, could hardly count as a “fool“ ]]

You haven’t understood the concept of юродивый. It has nothing to do with intellect. It’s about taking a moral position – a deliberate step which leaves one at a disadvantage, usually of an economic or status-related kind. This kind of misreading arises from looking up individual words in dictionaries. I usually find westerners are so locked inside their money-making mentality that they cannot fathom selfless actions. You very wrongly use the term ‘Insanity’ for them.

Shostakovich remains an outstanding example of such bravery in the 20th century. You are utterly wrong to dismiss Volkov’s explanation. Sitting in your European university while pouring scorn on the people who knew and talked to Shostakovich ‘because you know better’, you’ve simply made yourself into the fool.

Violone –

Thank you for your passionate response! It is exactly the energy that I dearly love about the Slipped Disk readership. In the classical world, we are so often polite to a fault, and I appreciate you ability to just say what you believe. I must mention, however, that the person responding to the Reader Question is a German, and the Vice President of the German Shostakovich Society. To call someone a “fool“ is quite a strong statement. I am not sure it is the best way to make your point heard.

Agree. The comments of these experts seem to me way off the mark, down to such details as Stalin’s more vegetarian actions, which were in fact careful and clever.

He once warned his swaggering eldest son that, in effect: — You are not Stalin, even I’m not Stalin, Stalin doesn’t exist, I have to recreate him every day.

It was Shostakovich’s special burden to preserve himself alive, so that we today can have 24 Preludes and Fugues for Piano Op 87 for example and whatever else of his that you love. His pre-Terror closeness to Mikhail Tukhachevsky made this survival an especially doubtful thing.

The composer was anxious by nature and terrified by the maze he found himself in. In my opinion he made a fine show of it. This nibbling-about-the-edges commentary, this presumption of holding the scales of judgement … yes, presumption is how it strikes me.

Thank you. That needed to be said.

Here are my Shostakovich questions:

1) Has Volkov offered an explanation for the material in Testimony that is recycled from earlier writings by Shostakovich? Did he have access to people in the Shostakovich circle who could have provided a basis for the more “controversial” material? (Reading Elizabeth Wilson’s book there do appear to be parallels between her interviewees’ recollections and the material in Testimony)

2) The 14th Symphony would seem to be antithetical to Socialist Realism. Were the cultural authorities less exacting by 1969? Did Shostakovich have enough prestige so that he had the freedom to write such a pessimistic and “modernist” (can’t think of a better word) work?

3) Is there a post-Soviet biography of Shostakovich in the Russian language? What efforts are being made in the area of Shostakovich research in present-day Russia?

Hi RegerFan! I like your pseudonym. I will send these questions along. Thanks for submitting.

Really, that needs to be answered? In what way would “cultural authorities” in the USSR not be “less exacting” in the late ’60s, than in the latter 1930s when one slight ‘wrong move’ could get you sent away forever (or worse). And as for your very last sentence, do you really believe an objective, ‘no holds barred’ biography of Shostakovich could be written and promoted in Putin’s Russia, i.e. today’s Russia? Look at how softened and Haydn-ized Gergiev’s own recordings of Shostakovich are.

Asking about the current status of research in Russia is in no way an evaluation of the reliability of those sources.

Asking about the official reception of a 1969 work does not imply a comparison with the situation in the 1930’s.

In Shakespeare’s dramas the fool is always the wisest of the lot.

My view (not very deeply informed, I readily admit) has always been that, for the Soviet regime (which always liked to present itself to the outer world as robust, healthy and wonderful) it would have been foolish to get rid of Shostakovich after the huge international success of the seventh symphony

Great discussion everyone! It’s a real book club – I love how everyone is getting into it. And – how not only do people disagree but they go further and show their opinions – their solutions. I remember many heated discussions in university literature classes, and this feels more like that. Let’s learn from each other!

In spite of Shostakovich’s historical biography (which will never really be settled), he remains the most uneven popular composer of the 20th century, in my opinion. I’m one who still looks at the work, not the man or woman.

That makes sense in most situations. But in the case of Shostakovich, you have to at least understand that era and its circumstances.