The Beethoven 9th that stopped the world

mainWelcome to the 112th work in the Slipped Disc/Idagio Beethoven Edition

Symphony No. 9 in D minor op. 125 (part 5)

((1 How Beethoven wrote it here. 2 How the world changed it here. 3 How do you choose a Ninth here. 4 Furtwangler or Karajan? here)

A month after the fall of the Berlin Wall in November 1989, Leonard Bernstein brought together musicians from Germany and the four former occupying powers to perform Beethoven’s ninth symphony on Christmas Day in East Berlin. In the text he substituted ‘freiheit’ (freedom) for ‘freude’ (joy) as a token of the excitement the West was experiencing at the defeat of totalitarian Communism. Bernstein said: ‘I feel this is a heaven-sent moment to sing “Freiheit” wherever the score indicates the word “Freude”. If ever there was a historic time to take an academic risk in the name of human joy, this is it, and I am sure we have Beethoven’s blessing. “Es lebe die Freiheit!”’

It was a difficult feat to pull off and the concert was more momentous on the day than memorable in the long term. It engaged with a moment in history and, like history, was messy in its component parts and resolutions. Only in the Adagio does Bernstein appear completely comfortable with his patchwork ensemble. The choral finale is unconvincing and you do not have look too closely at Bernstein’s face to see his dissatisfaction with both massed and solo voices. It was a great occasion, more showbiz than Beethoven.

While in Berlin Bernstein chipped away a chunk of wall and shipped it home. This concert was to be his last grand public statement. Aged 71, his organs were giving way to a lifetime of smoking, alcohol and other abuses. He died ten months later, aged 72. The concert lives on more in legend than in substance.

Beethoven’s ninth, to be fair, was not Bernstein’s signature work. Flamboyant and exhibitionist, Bernstein made big gestures when small ones might have sufficed and grew bored at the more intricate expanses of recapitulation. In the great expanses of Beethoven’s ninth, he placed philosophical meaning above detailed precision and fluffed some of the subtler suggestions. If you want to hear Bernstein conduct Beethoven’s ninth, the Vienna recording of 1979 is the one to have – not least for the spectacular opera chorus and soloists – Dame Gwyneth Jones, Hanna Schwarz, René Kollo and the unsurpassed bass introduction of Kurt Moll. Bernstein had a tremendous aptitude for choral sound and a great chorus conductor can make the difference between success and failure in the Ninth.

Who were the best at transforming amateurs into a formidable force?

Lorin Maazel, who died in 2014, was long ranked among the great conductors, although his performances were sometimes dismissed as ‘cold’ or ‘calculating’. The first American to conduct at Bayreuth, Maazel went on to head the Vienna Opera, the Bavarian Radio orchestra and the New York Philharmonic. Technically, in terms of clarity of beat and accuracy of note, he was the top baton of his generation. His memory was phenomenal and his psychlogical insight into players’ needs unusually penetrating. Some said he was too clever for his own good, which was more than half-true. He was quickly bored and some of his performances betray a loss of concentration.

But when he wanted to deliver there are few who could match his skill at raising musicians above their known abilities. His Ninth at Cleveland, where he succeeded George Szell as music director in 1972, is a major statement. The orchestral playing in the first three movements is outstanding and exquisitely phrased. The unexpected bonus is the Cleveland Chorus which burst forth on this recording as the equal of any in the world, lifting the finale into an altogether unexpected transcendence. The soloists – Lucia Popp, Elena Obraztsova, Jon Vickers and Martti Talvela are possibly the finest pack ever assembled. The vocal sound makes this a Ninth to reckon with forever.

By way of complete contrast, Claudio Abbado was chaotic and meddlesome in rehearsal, dwelling on small points at the expense of the whole. He tended to save revelation for the concert itself, surprising the players with the totality of his concept. As head of La Scala and the Vienna Opera, he knew voice and chorus as intricately as any of his colleagues and made some tremendous opera recordings.

His 1987 recording of the Ninth uses the Vienna Philharmonic and the Opera chorus, which sounds a tad undercooked. It is dreamily slow at 72 minutes and not altogether convincing. A decade later, as Karajan’s successor at the Berlin Philharmonic Abbado decided on a different choral timbre. The voices on his 1996 Berlin recording of Beethoven’s 9th belong to the Eric Ericson Chamber Choir of Stockholm, a group schooled in a capella singing and in atonal modern scores. For passion, power and clarity, the Swedish voices – the women’s especially – are unbeatable; the soloists, too – Karita Mattila, Thomas Moser, Thomas Quasthoff and Violeta Urmana – are a winning hand. Abbado cuts ten minutes off his previous best/worst. What was he thinking in Vienna?

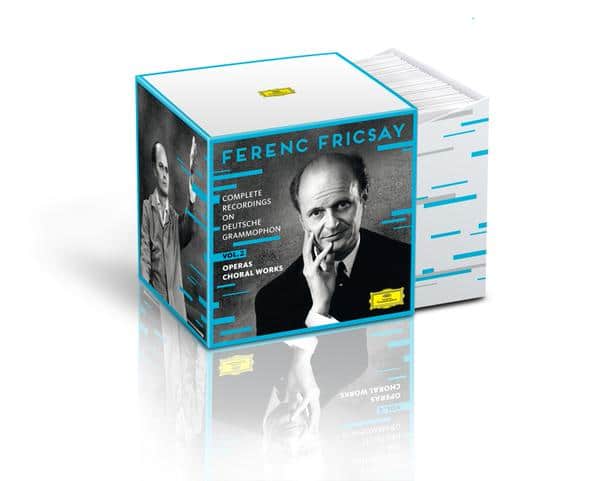

Well executed as these performances are, they are trumped by (in my view) a supreme master of choral direction. Ferenc Fricsay was brought to Berlin by Elsa Schiller in 1947 to head the radio orchestra in the US zone. Hungarian and half-Jewish, he was alienated by the former Reich capital and relied on Schiller’s moral support to keep his sanity. When Schiller moved from the radio in 1948 to be artistic head of Deutsch Grammophon, Fricsay was her trophy signing.

He fulfilled her faith in him with impeccable, best-selling recordings of major operas and symphonies. Stricken with stomach cancer (he died aged 48 in 1963), he worked tirelessly, achieving astonishing recordings of the Verdi, Mozart and Dvorak requiems, arguably the best on record.

Set loose on Beethoven’s ninth symphony in 1957 he took a big risk with an amateur cathedral chorus when he could have summoned a professional opera ensemble. Fricsay knew what he was doing, sensing that amateurs would give him best silence and the precise dynamic that he sought. His soloists – Irmgard Seefried, Maureen Forrester, Ernst Haefliger, Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau – are as good as it gets and the Berlin Philharmonic play far more flexibly than they are used to with Karajan. This is one of the immortal Ninths, a cert for our final shortlist, which will appear tomorrow.

Comments