Just this once, Beethoven shows us his workings

mainWelcome to the 41st work in the Slipped Disc/Idagio Beethoven Edition

Leonore overtures 1,2 and 3, opus 138, 72a and 72b

A composer of Beethoven’s unshakeable self-assurance does not let anyone see what goes on behind the making of a new work. He may leave messy sketches for abandoned pieces and a few doodles for works in progress, but Beethoven does not on the whole reveal to outside eyes the struggles that he endures in the act of creation, let alone his occasional ambivalence about the material he is moulding.

The great exception is his opera Fidelio, a work that he revised twice after its 1805 premiere and which he furnished with four different overtures, each of which reveals hesitations, second thoughts, uncertainties and insecurities that are quite untypical to this most confident of composers. Two of these overtures are in general use, the other two esoteric. Sorting out which is what is not the easiest of tasks. At the risk of over-simplification, I shall try to keep the process as clear as I can. Bear in mind, though, that this was the overture that awoke Richard Wagner, aged 13, to the possibilities of opera. ‘The direct result of this (1826) performance,’ he wrote, ‘was my intense longing to compose something that would give me a similar feeling of satisfaction.’

Beethoven was persuaded to write an opera in 1803 by Emanuel Schikaneder, librettist of Mozart’s Magic Flute and co-owner of the Theater an der Wien. Schikaneder, looking for a second hit with his name on it, tempted Beethoven with promises of a respectable fee and a free apartment in the theatre complex. Beethoven, often nervous at the approach of rent day, accepted with delight and started work.

Schikaneder’s libretto turned out to be unsuitable. Titled Vesta’s Fire, its central character was a Roman woman with several lovers who became a vestal virgin (don’t ask). Beethoven, after sketching three or four scenes, gave up. ‘I have finally broken with Schikaneder,’ he told a colleague. ‘He held me back for six months, and I let myself be deceived because… I hoped he would produce something cleverer than the usual. How wrong I was… Imagine a Roman subject (of which I had been told nothing) with language and verses such as could come out of the mouths of women apple-sellers in the Vienna markets…’

Staying on rent-free at the theatre, Beethoven began an opera under the title Leonore, oder Der Triumph der ehelichen Liebe (the triumph of married love), adapted from a French play by Joseph Sonnleithner. Never one to waste good music, he used a page from Vesta in the climactic “O namenlose Freude” duet. The 3-act opera was staged in November 1805 under the name ‘Fidelio’ to avoid confusion with several other plays and operas called ‘Leonore’. The score that Beethoven published, however, was titled ‘Leonore’.

Vienna was under French occupation and the premiere, before a mostly military audience, went down badly. Its overture is now numbered Leonore 2.

Before the opera was restaged in April 1806, Beethoven shortened it to two acts and stuck on a fresh overture, Leonore 3. At the next revision in 1814 the opera was callled Fidelio and furnished with a fourth overture, known today as the Fidelio overture. The original Leonore no 1 overtured was tacked on posthumously to Beethoven’s catalogue as its final entry, opus 138. Still with me?

The four overtures have audible differences – an extra drum roll, a contemplative flush of strings – some experimental, others insubstantial. The main thing to remember is that Leonore 1 is much shorter than the others. It comes in at 9-10 minutes, while Leonore 2 and 3 run to 14 minutes or more. In George Szell’s exhilarating 1968 interpretation it sounds like an invitation to all sorts of possibilities, many of them nothing to do with the prison drama that Beethoven is about to enact. Szell delivers Leonore 2 on the same recording for ease of reference, although only people writing a doctoral thesis will want to attempt repeated comparison. There are plenty more recordings of Leonore 1 and 2, the instantly recommendable ones including the no-nonsense John Eliot Gardiner, the authoritative Fritz Busch (1950), the unassumingly satisfying Wolfgang Sawallisch , the enegretic Günter Wand (1991), the imposing Bernard Haitink with the London Symphony Orchestra (2005), and the unaccountably underrated Stanisław Skrowaczewski with the Minnesota Orchestra in 1994.

But the best known and most performed Leonore overture is number 3 and that acquired an independent existence around the turn of the 20th century when Gustav Mahler, director of the Vienna Opera, inserted it into Fidelio as an orchestral interlude in the middle of the second act, after the prison scene and ahead of the finale, in order to heighten the drama. He went on to liberate the overture altogether from the opera, performing it as a concert item no fewer than 18 times. Mahler made extensive changes, known as ‘retouches’ to Beethoven’s instrumentation, principally by cutting back the strings and giving greater prominence to the brass. Leonore 3 thus became the best known of the four overtures.

Bruno Walter, Mahler’s closest disciple, gives the clearest indication as to how Mahler’s version might have sounded with a 1936 Vienna Philharmonic recording which has Mahler’s brother-in-law Arnold Rosé in his customary front seat, directing the strings. The approach alternates leisurely charm with unprovoked aggression, a peculiarly Viennese combination that I find profoundly unsettling, especially in the closing pages, from 11 minutes onwards.

A couple of years later, in Dresden, Karl Böhm presents an expensive velvet glove with a mailed fist that bursts through at 12.30. Böhm was a brilliant theatrical musician and a sworn Nazi; he must have known what he was delivering to the microphones. Wilhelm Furtwängler in Vienna, June 1944, is almost his antipode, introspective where Böhm exaggerates and suggestive where he is over-explicit. This is another of those inexplicable Furtwängler performances that imprints a date/time stamp on the music as it is heard.

Ferenc Fricsay, a Hungarian who conducted Berlin’s radio orchestra in the 1950s, gives an uplifting 1958 account of the overture with the Berlin Philharmonic and another, two minutes slower and three years later with his own ensemble. The second is an exercise in taking all of the beauties out of the score, holding them up to the light, examining them from all angles and replacing them in perfect order. Taken together, these two performances amount to a masterclass in the maestro art, an analysis of all the possibilities in an important score. Against all my expectations, Sir Georg Solti and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra reflect something of Fricsay’s inquisitive approach in their late account of this score in 1989, albeit faster and much louder.

You want slow? There’s Sergiu Celibidache at 16.22, to no obvious purpose. You want exciting? Bernstein and the NY Phil. You want small-scale? Daniel Harding and Deutsche Kammerphilharmonie Bremen do tender and beautiful. Dramatic and compact? Nikolaus Harnoncourt and the Chamber Orchestra of Europe take some beating. The range of dynamics and the internal tempi are just right.

That’s enough of overtures. Tomorrow, we’ll assess the whole opera.

UPDATE: Did someone say Klemperer? Watch this space.

Of the four overtures I prefer Leonora 1 and 2.

My performances of choice: Klemperer.

There is no doubt that the 3rd Leonore Overture is the best of all the rest, but too long for a relatively short opera (Wagner could get away with his prelude to Mastersingers, because the rest of the work itself is so lengthy). As ever Beethoven came up with the most appropriate score at the end. In relationship to Gustav Mahler’s re-orchestrations of Beethoven, it was controversial even in his own life time, but as he was a genius it would be worth hearing. Oslo Philharmonic will hopefully be performing Beethoven’s 9th Symphony in Mahler’s orchestration in May , provided Corona virus hysteria does not put an end to it.

DG is releasing William Steinberg’s Beethoven symphonies in May, and he did the Mahler version of the 9th.

Wow, Norman, no mention for the #3 of Klemperer? Toscanini? Karajan? Knappertsbusch?

Yet you cite a conducting non-entity such as Harding.

Perhaps you’ll come to your senses when you discuss the entire opera.

(And you Harding fans – save your invective. You all know he can’t hold a candle to the four giants I mention.)

Sorry, but you missed lots of good ones. Muti and Philadelphia; Daniel Barenboim and La Scala; Antonio Pappano and the Royal Opera;and, perhaps my favorite, Otto Klemperer and the Philarmonia (justly considered a classic). There are many more good ones.

Klemperer recorded all the overtures, too. Just saying.

The music of ‘O namenlose Freude!’ was originally conceived for the Roman woman of Schikaneder’s libretto, when she discovered that she had turned into a virgin.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HVyiGkMeyyM

https://testament.co.uk/quickview/index/view/id/188

The problem with the overtures demonstrates that Beethoven was not an opera composer, though Fidelio is a great work of music, and, perhaps, Leonore (as John Eliot Gardiner has pointed out) is a still greater one, and certainly a more radical one. As a concert overture Leonore 3 (and 2) work, but Leonore 3 gives away the whole plot and pre-empts the dramatic high-point of the opera. Beethoven, of course, got the opera overture right with ‘Fidelio’, and by then, I think he had realized Mozart was the model!

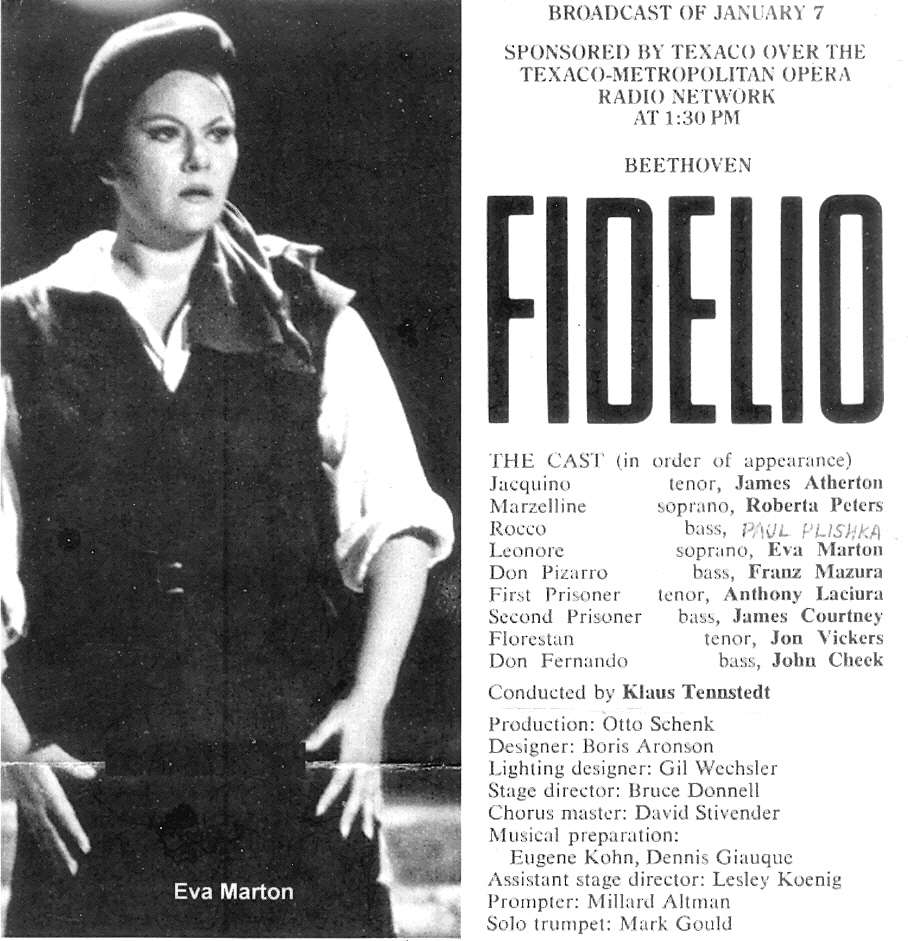

Leonora no.3 indeed gives the game away. On the other hand, it *can* work as a recapitulation of the drama when played, Mahler-style, between the two scenes of Act II. Certainly, one would not want to be without the incandescent performance that Klaus Tennstedt conducted as part of a Met radio broadcast of the whole opera (a recording to which our good host has linked in the past).

Welcome back, Hugh!

If you are referring to the late Baron Dacre of Glanton, he was my correspondent in Oxford…

I was… so that makes you…John Tooley or some such?!

For stereo sound for sure I go with Szell/Cleveland.

I was lucky enough to come upon good quality, nearly mint, Victor shellacs of Toscanini’s 1939 recording for HMV of the Leonore No. 1 with the BBC Symphony. In addition to being a thrilling and dramatic performance, it is a chance to hear prime Toscanini without the “stuffed up nose” sonics that Victor came to prefer seemingly as the RCA technology side of the corporation held more sway on such matters. With just that bit more of “air” around the music, one hears far more subtlety in the phrasing and rubato than one does in many of the Toscanini NBC Symphony recordings – more like one hears in Toscanini’s NY Philharmonic recordings, which also benefit from being more “Victor” than “RCA Victor.”

Off topic perhaps but what I mean by RCA technology is that there came a time in the 1930s when the technology wizards at RCA felt that they could use recording technology to cut costs. Without the benefit of tape recording they attempted overdubbing so that what was recorded as a three sided set of shellac could be released as 2 sided, cheaper than the competition, but at the cost of compromised sound. Some recordings were transmitted to the studio via telephone lines resulting in about the deadest sound one can imagine. I think Flagstad’s Wagner with the San Francisco Symphony is an example. The Martinelli/

Jepson/Tibbet “Otello” excerpts and the Kipnis “Boris Godunov” excerpts are similarly dead, with the odd consequence that Victor recordings of a full decade earlier had better sound.

It’s a “rescue” opera, familiar from and perhaps influenced by Etienne Mehul, Daniel Frncois Esprit Auber, Cherubini, and Rossini, or Weber past and future. ‘Fidelio”‘ is as brassy as any of them. I’d love to see the faces of the first horns to take on “Abscheulicher”. Arthur Berv and Dennis Brain had no problem with it. Leonore 3 is no longer than the tone-poem Rossini wrote as overture to “William Tell”.

In his EMI set of Vienna origin, Furtwaengler plays the third Leonora overture between the two scenes of Act II to introduce the final scene’s opening chorus followed by the appearance of the good minister Don Fernando as deus ex machina, like the Hermit in “Freischuetz” or Sarastro in “Zauberfloete” to reassure us and make everything right.

One small point: the text refers to Leonore 1 as “the original” but that’s incorrect. It’s generally assumed these days that it postdates nos. 2 and 3. There’s no evidence that it was ever performed during the composer’s lifetime.