Does the ultimate Fidelio still hold sway?

mainWelcome to the 43rd work in the Slipped Disc/Idagio Beethoven Edition

Fidelio, opus 72 (continued from yesterday)

At the start of 1961, Otto Klemperer arrived in London to make his debut at Covent Garden at the age of 75. After a turbulent life, marred by periods of manic-depression and prolonged exile, poverty and ill-health, Klemperer was coming to be reocgnised as one of the last great masters. He had formed a productive relationship with the Philharmonia Orchestra in London and Water Legge had signed him to an extensive EMI contract that encompassed many of his performances. Covent Garden, too, came calling. Its general manager David Webster asked if Klemperer would care to revisit one of his life’s largest milestones.

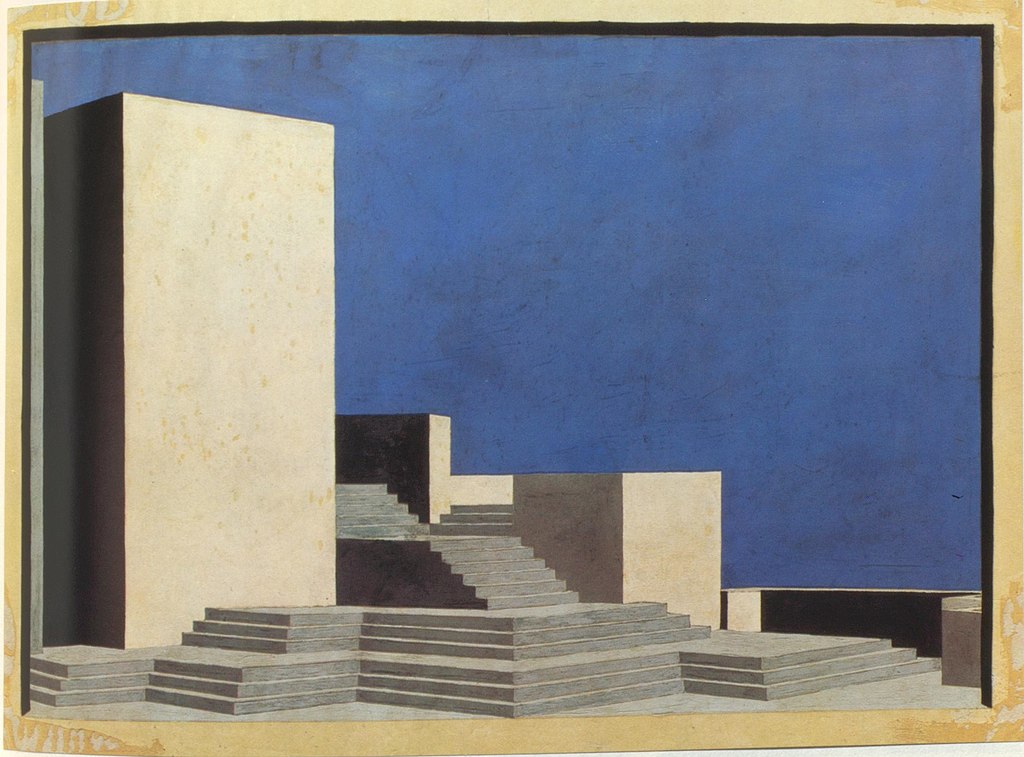

Back in 1927, Klemperer had taken charge of Berlin’s new Kroll Opera with the intention of turning the company into an incubator of modern music, art and design. His opening production, Fidelio, had sets by Ewald Dülberg arranged in cubist blocks which served as a model for contemporary opera production. Conservatives were horrified and Klemperer himself wondered if they had not gone too far. His arch-rival Bruno Walter responded four months later with an opportunistic Fidelio in traditional mode at the Charlottenburg opera house. It was all part of the ferment of Weimar-era Berlin, arguably the liveliest arts scene of all time.

Three years later, the Kroll was shut down. In 1933, Klemperer was hounded into exile and Düllberg died, tragically young, at 45. Their experiment, shortlived as it was, survived as legend. Now, more than 40 years later, Klemperer was being asked to conduct Fidelio, never a box-office draw, in the ambitious though delapidated setting of the Royal Opera House. His daughter Lotte wrote: ‘I almost had to crawl on all fours to get into the orchestral pit.’

Klemperer presided at piano rehearsals with a cast led by Sena Jurinac as Leonore and the Canadian tenor Jon Vickers as Florestan. The old man had not conducted an opera for 11 years and needed time to adjust. Legge reported to his EMI bosses that the entire run had sold out within 24 hours. On the opening night, February 24, 1961, the manipulative Legge visited Klemperer in the interval to tell him that the ‘public is stone-cold’. The reviews next morning were ecstatic. Almost 60 years later, a writer in the Times could remember ‘every detail’.

For the recording, a year later, Legge proposed replacing the entire cast except for Vickers and Gottlob Frick (who sang Rocco). Klemperer stuck by his singers. In the end, for various reasons, Jurinac made way for Christa Ludwig and the Bavarian Ingeborg Hallstein was brought in as a last minute Marzelline. Their voices in the first-act trio with Frick are marvellously fresh, every note nailed and the balance perfectly poised. You need hardly listen to more to know that the conductor is guiding every nuance. In the second act, the former truck-driver Vickers sings like a heavenly cherub.

The recording was made at Kingsway Hall with the Philharmonia Orchestra and chorus in place of unavailable Covent Garden forces. The set has been regarded ever since as the last word in Fidelio, one of the greatest recorded operas. Is that justified? On most counts, absolutely. Klemperer’s tempi are taut and organic, suited to the singing voice while maintaining a high wire of dramatic tension. The concluding sextet of voices is a miracle of human engineering. Nothing jars. The verdict of critics over more than half a century is upheld by consensus.

And yet.

In 2004, a small UK label called Testament secured the rights to release the actual Covent Garden performance of February 24, 1961, with Vickers, Jurinac and the Australian Elsie Morison, who soon gave up singing after marrying the conductor Rafael Kubelik. Both women have greater immediacy than their EMI replacements. Vickers is phenomenal and Hans Hotter (whom Legge replaced with Ludwig’s husband Walter Berry) is deeply affecting as the fearsome jail chief Pizarro.

There are two caveats. The stage show has screeds of spoken German that were omitted from the EMI set and the pit sound and pit-stage balance are unsatisfactory, with the voices darkly recessed. It’s an inspired performance but the ultimate Fidelio recording remains the studio version of 1962. The Testament tape is not yet available on Idagio. It can, however, be accessed on Youtube and you can compare it, minute by minute on your computer, with the Idagio stream of the EMI recording. Both are indisputably historic. Let us know your conclusions.

Klemperer lived the to great age of 88, dying in Zurich in July 1973. The recordings of his final decade generated equal measures of admiration and controversy as his habitual capriciousness alternated with gathering frailty. The results can be inconsistent. Against a heart-stopping account of Mahler’s Das Lied von der Erde with Christa Ludwig and Fritz Wunderlich (in which the soloists never met), there is a performance of Mahler’s seventh symphony which is almost wilfully perverse – challenging and infuriating by equal measure.

As a Beethoven conductor, his accounts of the 5th and 7th symphonies (in a complete cycle with the Philharmonia) are magisterial, as is his set of the piano concertos with the young Daniel Barenboim, who revered him ever after. It’s hard to categorise, given his variability, precisely which personal qualities Otto Klemperer brought to Beethoven. But, having known his daughter Lotte quite well, I gained a sense of certain affinities between her father and the composer. Both were gruff, mercurial, often misanthropic (was Beethoven bipolar?). Both had huge heads and were plagued with physical illness. Both believed in something larger than themselves.

There was an empathy between Klemperer and Beethoven. You can appreciate it in these recordings.

David Webester from Covent Garden?

Nice. Lots of loving detail. Good job.

I know that Walter Legge was a total SOB, controlling, demanding, unethical…but damn, do we owe him. His love and dedication to great music left us with recordings like this Fidelio that we should all be grateful for.

Good point about Legge. Among the many priceless recordings we owe him are those of Dinu Lipatti.

Absolutely….and he married Schwartzkopfh and championed her through a great career…and recorded a young Karajan when he was at his very best.

There is also a Klemperer live recording from Budapest in 1948: Mátyás, Báthy, Rösler, Maleczky, Székely.

The Tennstedt, made in 1984 in New York, can be heard online: Peters, Marton, Vickers, Mazura, Plishka.

And of course the most exciting Fidelio, Böhm in 1978 in Munich, is on CD: Popp, Behrens, King, McIntyre, Moll.

The 1978 Munich is just spectacular because of the incandescent breathtaking Leonore of Hildegard Behrens, who incidentally also sang one performance with Vickers and Tennstedt at the Met in 1984, and of course I was there live and will not soon forget it! all three of them just magnificent. And a tape of that performance does exist, though in not as good sound as the Marton, which was the radio broadcast. Behrens at the time was singing Isolde during that week at the Met, and was asked at the last minute to replace an ailing Marton. What a reunion it was with the great Vickers, with whom she had sung many a performance and had great chemistry!

The Testament issue, to which by coincidence I have been listening for the past day or two, seems to have been an ‘in-house’ recording made by the BBC as a trial balloon for the actual broadcast on 7 March, which has also been on CD (Melodram MEL 27076). I far prefer either of them to the studio recording, which I have always found a trifle dull. Vickers is actually in better form on the Karajan EMI set. Enthusiasts can also find performances by the Furtive Wangler (Salzburg 1950), Erich Kleiber (Cologne Radio 1956) and Gui (RAI 1952, with one or two bits sadly missing from the tape). And then there is Bernstein…

I have the Testament recording in my music library but don’t listen to it often. The ending is such a good rush. I have seen the opera a couple of times and find it a frustrating experience. Much as I love Beethoven’s music, opera was not a natural home for him. My library also contains the Harnoncourt and Abbado recordings. Flashes of good and bad and an unsatisfactory whole. It’s likely a minority opinion but I prefer to listen to Leonore over Fidelio.

I’ve always found the 1950 Furtwängler painfully slow and heavy as if written by Ludwig Van Wagner but still a must have because of the near dream cast. I’d still go with Bruno Walter’s 1941 Met broadcast performance with Flagstad if I could only keep one. There’s also a live Jan 1971 Met broadcast performance under Böhm with Rysanek on fire triumphing over her vocal inequalities and Vickers at his peak. Both conductors, by the way, fully justify the Mahler Leonore 3 interpolation as it is truly cathartic with each. (Likewise under Tennstedt.)

Dülberg, not Düllberg. And he died at 44, not 45, the poor, great man. https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ewald_D%C3%BClberg

this review is one of your best, Norman, thank you, although the set I reach for will always be Furtwaengler’s EMI Vienna recording, with the live Salzburg in reserve. I also learn from anything Tully Potter writes, albeit furtively. And another vote for Hans Hotter’s Don Pizarro.

About time that the Klemperer omission was rectified. But the article has lots of annoying typos. Employ some copy editors, please.

Oh, please. It was a terrific and informative article. Publishing online is almost like performing live where perhaps every note is not perfect, but as a whole there is excellence. We now have the ability to go back and airbrush offending typographical and other errors or omissions in such online offerings. Let’s not be obsessed with such petty fault-finding.

I’m privileged to have been the assistant Sound Engineer on the EMI recording at Kingsway Hall. My very first session had been the audition recording of The Beatles 🙂 and this was not long after that, so not a bad start for a young lad!

The recording tape machines, which I was in charge of, were in the lower depths of Kingsway Hall and so I couldn’t watch the great man at work (at the same time though, it also meant that I didn’t have to sit near Walter Legge!), But I had plenty of opportunities later, when we were back in Abbey Road. Klemperer never spoke to such an underling as me, but I watched him with fascination – I had assumed that all conductors raved and shouted at their orchestras, but Klemperer sat perched on a high stool and, suffering from a stroke, hardly moved. But the orchestra played like demons!

The second Fidelio recording I was involved in was with Charles Mackerras, some 35 years later, by which time I was the tape editor. I love the recording (though admittedly, it’s not a great one), as I was able to contribute to the production with some bits of sound design (for example, running the dialogue over the Marching Band in the Governor’s entrance…)

Thanks for the fascinating recollections. Am I correct in my assumption that Sena Jurinac would have been contractually unavailable to EMI? Especially as she had just recorded Fidelio for Westminster with Knappertsbusch. Anyway, Ludwig was an inspired choice.

Thank you for this evocative reminiscence.

A key point is that the EMI set does not have Leonora No.3… and this is where the crackle of electricity from the live performances is most obvious, and serves to point up what is missing from the studio recording.

Allegedly, when Legge went to see Klemperer in the interval, as you relate, not only did it inspire him the more in Act 2, but he was moved to stand up for the closing chorus (scene?), which, by then, he rarely did.

I also recall some orchestra player of the time saying that they used to follow him by the movement of his trouser seams, which was clearer than his actual beat.

Not only did Lotte have to crawl in to the pit, but Klemperer used to enter not from one side of the pit but from a room at the back, which was closer and easier for him, and where he was allowed to smoke during the intervals. It had been the off stage band room re-purposed…. can any fill in any details?

Many adjectives come to mind when I think of Jon Vickers, but “cherubic” is not one of them.

Jurinac was a real dramatic soprano, much stronger and immediate than Christa Ludwig.

Walter Berry did not pack enough meat for Pizarro. He went through a phase in his career when he tried to sing parts which were very much too hefty for his little voice-let. His Alberich is embarrassing, and he had to drop out in the middle of his performance as Wotan in DIE WALKURE.

His live Pizarro at the Met in 1971 under Bohm is splendid.

The Klemperer FIDELIO was my first recording of this opera and has remained a favorite for decades. In 1962, Christa Ludwig could sing anything and she’s thrilling on this set, as is Vickers. There is such a sense of urgency to Klemperer’s conducting (the same with the Mahler Das Lied von der Erde he recorded for EMI). Another set I like very much is a Michael Halasz-led FIDELIO with Inga Nielsen, Gosta Winberg, Kurt Moll, and Alan Titus on the Naxos label. I’ve never heard the Fricsay set, but I can’t imagine Rysanek ever having a settled-enough middle voice to make me care about her Leonore. In the theater, she was magical. Ditto Gwyneth Jones the year after her Met debut.

I bought both the Klemperer Fidelio sets mentioned here but ultimately find them both well sung but disappointingly lacking in drama compared with the sets conducted by Karajan (EMI) and Bernstein (DG). I know to prefer Karajan to Klemperer in Fidelio is the ultimate heresy in the eyes of many people but the opera comes over in a vastly more dramatic fashion even though Klemperer has marginally the better cast. It is funny that many people I have talked to have the same (guilty) feelings as I do!

I am sorry, but I an amateur. I don’t read music. Does Florestan’s “Gott! Welch Dunkel hier!” on the beginning of second act calls for a crescendo? If it does, Vickers is totally flat. There is one thing I never understood, this admiration for Vickers. As wells for that other Canadian that rhymes with gold. To each his own taste. I will not discuss.

The most formidable Fidelio I’ve ever seen or heard was a concert semi-staged performance back in 2015 in San Francisco with Nina Stemme and Brandon Jovanovich. MTT conducted. Jovanovich sang “Gott” with a spectacular crescendo. It was mesmerizing.

Can anyone explain why Solti did not conduct Decca’s 1964 Fidelio recording with Nilsson, McCracken, and Krause with the VPO instead of Maazel? Not that it would have been better or worse as a result but it seems to have been a project designed for their star conductor.

I have to admit that I personally can only consider DVD performances of operas, and exclude CDs from my collection. A personal view only, but I think the staging also has to be seen as well as heard.

Do people have a favourite recording of a staging that they would like to discuss?