Are American composers unfairly silenced?

mainTerry Teachout thinks they are.

The drama critic bangs the drum in the Wall Street Journal on their behalf, citing as evidence that ‘Some quick research shows that Harris, Mennin, Piston, Schuman and Elliott Carter (who together wrote more than 100 concert symphonic works) had, in the past five years, a total of just 20 performances by U.S. orchestras.’

That, you might say, is a first world problem. If US orchs don’t think their own composers will fill a hall, why should anyone else imagine that they are worth performing?

But there’s more to the problem than hardcore capitalist economics.

There is a measure of resistance in some quarters to US symphonic music and it has been embedded for quite a while. In a culture swamped by American movies, pop music, fashion and art, some European and American aesthetes try to preserve the concert hall – perhaps unfairly – as a US-free zone.

Tough on US composers, but there you are.

Next year, however, when Steve Reich and Philip Glass turn 80 we will be inundated with their works.

The widespread lack of support by American orchestras for homegrown music, past and present, is why I started the American Music Project in 2014. AMP has commissioned and premiered works by Amy Wurtz and Geoffrey Gordon in Chicago and New York, programs that also included music of David Diamond, Irving Fine, John Cage, Earle Brown and John Luther Adams. This past season AMP grants have facilitated performances of American music in Illinois, Oregon, Texas and elsewhere.

AMP is currently accepting applications for grants in the 2016-17 season, so apply today at http://americanmusicproject.net

Keep up the great work, Lawrence! You are doing an incredible service for American music and I applaud you! Fortunately, there are many organizations and private individuals making sure new and old American music is performed (as well as recorded). I’ve tried to do my small part bringing new works for piano and orchestra (adding chorus for two) to audiences (and in some cases recordings) by Ellen Taaffe Zwilich, William Bolcom, Charles Strouse, Richard Danielpour, Lowell Liebermann, Kenneth Fuchs, Lucas Richman, Jake Runestad, Marjorie Rusche, PDQ Bach, popular artists Peter Tork, Jimmy Webb, Neil Sedaka, Dick Tunney, a new 2019 project with Christopher Theofanidis, and keeping older works by Keith Emerson and Leroy Anderson in the forefront. Their legacy is indeed a wealth of music, and I suppose it takes individual artists and conductors to cultivate the music that means much to them to keep the music alive. For one, my hat is off to Leonard Slatkin who consistently supports music which deserves to be heard. There are many conductors in the US who cultivate a wide repertoire, and I have heard many fantastic performances throughout the country with works I had never heard of. From the business side, it is extremely challenging to put forth works in front of audiences which they do not know. That can open a huge topic of discussion, and I leave that to the conductors who have to deal with the business and marketing side of their orchestras. I respect them highly for doing what they do to keep their orchestras out there.

“Next year, however, when Steve Reich and Philip Glass turn 80 we will be inundated with their works.”

Where will all this Philip Glass inundation occur? The LA Opera is going to do “Akhnaten” this fall, but it will likely sell out every seat. I am going to his 80th birthday concert at Carnegie Hall at the end of next January, but that is with the Bruckner Orchestra Linz (not a US orchestra). After that, the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill is putting on a “Glass Week” celebration for him. I don’t know of any regular US orchestras doing much of anything. Most concerts with Glass music are through his own touring.

No love for Ives? I’d like to hear his symphonies in concert but it is the short stuff like Unanswered Question that gets programmed in Los Angeles. Howard Hanson wrote some good stuff also. I’ll try not to rant about what does get played here.

The first orchestral concert that I went to was one with the LA Phil, in the early 1970s. For the first half of the concert, Zubin Mehta programmed Bach keyboard works (I still remember the soloist – George Malcolm). For the second half, he programmed Ives’ Fourth Symphony. I can still remember the excitement I felt (and I was young then) as the unexpected sounds washed over me. That got me hooked on classical music.

Thierry Fischer will be conducting the Utah Symphony in all four of the Ives symphonies this upcoming season. I’m planning to drive the 350 miles to hear the Fourth.

I heard a roof-raising Ives’s Second in the early ’80s with the Oakland Symphony and got a big kick out of it. I think it was paired with Beethoven’s Sixth because conductor Calvin Simmons’s podium talk spoke to the different pictures each one painted. Simmons drowned in a boating accident a year or two later – a genuine loss to the classical music world.

Just because someone, or a group or people, has/ve a large output (“over 100 symphonic works”!) doesn’t mean that they are necessarily appealing, or desirable, to listen to.

They might be. But quantity is not quality, and neither is necessarily commercial appeal.

Not only is American music not being performed, American female composers are definitely not being supported at home. In 1983 I was a female music composition student at a major university in this country. There was NO mention to me that Ellen Taafe Zwilich had won the 1983 Pulitzer Prize for music that year. She was the first female to win the prize. Her music was never played in class. Yet Terry Riley, Steven Reich, and others were played. She was never mentioned, and I graduated in 1985, the only female in the music composition department.

Winners of the Pulitzer Prize in music composition are announced the same way for all winners, male and female. You’re suggesting that the Pulitzer Prize Committee kept the news on Ellen Taaffe Zwilich under wraps. Also, you seem to be saying that you expected to be personally informed about the decision. Why? Yes, being the first female winner of the Pulitzer is a great thing, but half of Pulitzer composers have gone nowhere in particular, and I can sight perhaps better female composers who didn’t get Pulitzer’s: Ruth Crawford Seeger for one.

“Harris, Mennin, Piston, Schuman” should not be uttered in the same sentence as “Elliott Carter”.

The former are incredible symphonists, expressive and accessible in their modernism.

The latter is a pretentious avant-garde academic who didn’t care a whit for the audience.

If you are trying to sell the music of the former, then don’t mention the latter in the same breath as though they all have something in common.

I wouldn’t try to sell Debussy and Ravel by including Boulez’ name in the mix.

“You’re going to LOVE fruit, fruit are delicious.. try some pears, apples, grapes, raw kidney”. See? You have to put things together that at least bear a certain similarity.

I’m in total agreement with you, Mikey.

Apparently you have never heard any of Carter’s earlier works like the Holiday Overture, his first symphony and the ballets Pocahontas and The Minotaur, which are very much in league with the music of Copland, Harris, Piston, Schuman, etc. If you had, you would not label him as a “pretentious avant-garde academic” as his music evolved from neo-classicism to his own brand of modernism.

This also applies to Boulez who, in spite of all his serial machinations, incorporates the same impressionistic orchestral palette as Debussy and Ravel.

We’re just going to have to agree to disagree on this.

My idea of hell would be to be forced to listen to the “music” of Philip Glass.

What awful, puerile, mind-numbing s**t it is.

+1

I’d like to see you write Etude 11, Etude 20, or Songs and Poems for Solo Cello! Three Academy Award nominations for Best Score. Copied more than any other composer.

I would never write crap like that, even if I were a composer.

And you’re saying that three Academy Award nominations (the AAs have been a joke for years) and the fact that Glass is copied (I’d need to see some documentation regarding your “more than any composer” claim) automatically gives his “music” some sort of artistic credibility?

Puh-leeze.

It’s just a matter of how you use Philip Glass’ works. They are perfect for the Guantanamo Philharmonic.

You could write a book about this problem, but the answer is not that hard: music is an emotional experience, and when I need a degree in musicology or mathematics to understand something, count me out. The symphonies of people like Piston, Mennin, Sessions and so on are all technically perfect. But they lack the element of human emotion that makes symphonies by Beethoven, Tchaikovsky, Mahler, and Brahms so memorable and exciting. Too much American music is sterile. When you consider the average concert goer, they want something that they can hum the tune to, tap their foot along with, or have some other-worldly experience. Even in “modern” times the most popular symphonies of Prokofieff and Shostakovich are the ones easiest for people to recall tunes from: 1 & 5 for the former, and clearly 5 for the latter.

But there is some really good stuff, so why is it ignored?

Conductors don’t know it, and since it’s not in the hallowed standard repertoire, they have no interest. It’s also a matter of cost sometimes. Rental fees for scores and parts are in many cases insanely high.

A related problem is American music directors – it’s shocking how many orchestras hire from Europe, Asia, even South America. Then the chances of American composers getting play time decreases even more.

To any conductors in the USA reading: look at Amy Beach, George Chadwick, composers like Converse, Carpenter, Gillis, Willson. You’ll find a lot of wonderful, exciting music that could really rejuvenate your tired, worn out programming.

Some fair points, but Piston lacks human emotion? It’s been a while since I’ve listened to any of his symphonies, but I recall his music as quite tuneful, even if the tunes weren’t one you’d be whistling on the way out of the hall. But you can say the same about the early Dvorak symphonies (also rather neglected).

I think the more general problem is that audiences don’t know what they like; they like what they know. Most people don’t know Piston or Hanson so think they don’t want to hear it. But listening to them blind, they’d probably have no objection. Gerard Schwarz did admirable work in the late-80s in Seattle promoting Hanson, Diamond and Piston (and recording a lot of their works). But there seems to be little momentum from that.

The most regrettable of all, IMHO, is that Harold Shapero’s great Symphony for Classical Orchestra continues to wallow in obscurity.

The American Symphony Orchestra is performing Shapero’s Symphony for Classical Orchestra plus works by other American midcentury modernists in November, a partial amelioration: http://americansymphony.org/bostonians/

elliot carter fucking sucks so why would anyone play his shit music? i dont know the other composers, but they’re proabably not good.

William Schuman,for my money the greatest American symphonist of the 20tg century. David Diamond is also vastly underrated, same goes for Ned Rorem.

Cubs Fan should stick to baseball, where he/she may know what he/she’s talking about — although even baseball didn’t mean much in the 19th century, which this person has not emerged from.

Gee Paul, I don’t know exactly what your problem is. In fact I know quite a bit about what I’m talking about. I’ve played in orchestras for 40+ years. I’ve played the standard rep over and over. And ocassionally something new and different. And I’ve played a lot of 20th century music. Some great, some not. I’ve played all of the Hanson symphonies, except #5. Lot’s of Copland, Piston, and yes, some Schuman. And I know how audiences react. You want an audience to go away fulfilled, do the Tchaikovsky 5th – gets ’em everytime. The Schuman 5th, not so much. The Copland 1st – they walk out. I also go to a lot of concerts at home, out of state, and abroad. At home, the music I listen to is probably 80% from after 1900. For what it’s worth, Converse, Carpenter, Gillis and Willson are all 20th c composers – they just didn’t go down the ugly-music route. Please try to remember, I am talking about the average concert goer. Now, back to the Jurovski 5th…

The audience doesn’t know the Schuman 5th (which is the string symphony, which gets VERY few performances).

Obviously, they will not be quite as snthused by a work that requires getting to know. However, I’ll debate you until the end of days regarding the qualities of Schuman’s earlier symphonies. From the 3rd through to the 7th they are powerful, melodic, lyrical, and borderline tonal, works that deserve proper respect. If you think Schuman’s 5th is a hard one on audiences then I suspect you may not have heard it.

now, you’ve played in orchestras for 40 years.. are you talking community orchestras? or professional symphonies? the audiences for each are different, particularly when one takes location into consideration.

my clarinet quintet, a work certainly no less accessible than a Schuman symphony, was premiered a few months ago to a HUGE standing ovation, in a hall seating 600 that was sold-out. and this wasn’t even a “big city audience”. But they loved getting the chance to hear something they’d never heard before.

There was a 45 minute “talk to the composer” before the concert, which I imagine helped a great deal. it took me over a half hour to get from the hall to the exit after the concert. I was mobbed by audience members.

So you don’ need Tchaikowsky to keep your audience. You just need a deft touch when programming and a good means of presenting the material.

No one is silencing any of the American composers mentioned above. Most of them got their works performed once, and a few got their works played 2 or 3 times. Now, had they written something that the public actually wanted to listen to, their music would be played all the time. But, they didn’t – it’s that simple. Over all, their talents were academically oriented, and their music fulfilled their academic exercises, but not their public’s musical needs. When composers fail to communicate, their music disappears. By and large, the American composers mentioned here were skilled craftsmen, but their music lacked that extra ingredient that grips the public’s imagination, thus relegating much of the 20th Century American symphonic cannon to the graveyard. What exactly is that elusive ingredient, and why did it elude so many American composers?

It seems obvious that gifted composers don’t write to answer the need of audiences, but write what they themselves want to hear, and what they would like to share with listeners. The ‘American problem’ is not a local one, since it also reigns in Europe. Considering 20C music history, it is clear that the cause is the type of language, the general culture which moved away from humanism in the arts, and the cultivation of technological and materialistic utopianism. Pre-modern composers had the advantage that they were rooted in a tradition which offered so much in terms of expression.

If you really believe that then you don’t belong in a concert audience.

The symphonic works of Copland, Mennin, Schuman, Piston, Barber, Rorem, Harris, and so many others, are NOT “academic”. They are lyrical, beautiful works, full of melody, and engrossing harmony, inventive rhythms, fascinating colours, and appealing warmth and depth.

These composers have most definitely not “failed to communicate”.

I’ve been in love with the music of the composers I listed since the age of 16. You know what took me forever to appreciate? Tchaikowski. Verdi. All the go-to classics that are so often held up as shining examples of “what to do” when composing.

Funny thing is, when many of those now-popular “classic” works were premiered they were far from universally appreciated.

Odd that you are so quick to rebut someone’s negative opinion of composers you like, but in this thread you yourself already spoke disparagingly about Elliott Carter. I could make the same statements about Carter that you made defending Copland, Mennin, Schuman, Piston, Barber, Rorem, Harris, etc. I discovered Carter’s music at a similar age, so much of it spoke to me powerfully from the very first hearing, and I could spent hours effusing about its rhythms, colours, and “depth”.

It’s a pity that being yourself a fan of very niche composers hasn’t made you more appreciative of the immense diversity of tastes out there. And for what it’s worth, Carter cared very much about his audience and was known to express his gratitude to any fan telling him about their enjoyment of his music.

I don’t know how much of this music you have actually listened to, but these are fairly conservative figures whose music was widely listened to in major cultural centers. Leonard Bernstein recorded a fair amount of this music, and I know that as a musician, I played a fair bit of it and found it quite wonderful and quite audience-friendly.

Personally, I think the lack of hearings comes from the fact that they’re not Mahler, Brahms, Beethoven or any number of dozens of other mainstream ‘top 50’ composers that audiences in many markets insist on hearing. Really, I think it’s that simple.

In recent years, I’ve returned to Schuman and some of the others, purchasing complete sets of the Schuman symphonies (Howard Hanson also) and have enjoyed revisiting and reacquainting myself with this wonderful music.

When my local classical station plays Finlandia for the fiftieth time this year, or Grieg’s Peer Gynt for the fortieth, or some other work that’s been flattened into meaninglessness by repetition and over-exposure, I am thrilled to know there are hundreds of other interesting composers who have written music that is eminently listenable and well worth the time. With most of the people here, they are worthy of much more than occasional listening.

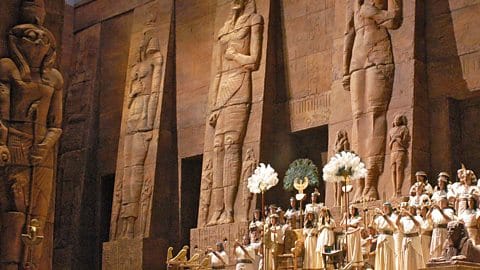

OK, off to listen to Barber’s Antony and Cleopatra now.

An unstated reason for the lack of performances and a less than enthusiastic reception by the audience is the quality of the performance, driven by the understanding of the conductor and his ability to convey that understanding to orchestra and auditors alike. I have heard many performances of American repertoire by celebrated and well meaning executants that were plainly and simply not good. This music must be studied and absorbed with the same seriousness that we devote to composers now considered canonical. Piston, Mennin, Barber, Creston, Flagello and many others were masters who created exceedingly communicative music. When I was preparing Hadley’s The Ocean in Kiev, the orchestra got very excited about the music; they came to the control room to hear takes, and asked me “is Hadley famous in America?” We performanced Hadley and McKay there, all first performances in that country, and at the end the audience was wild with applause and appreciation.

So, I know this music speaks. It needs repeated exposure, both for its executants and its audience. Think of it this way: if Mahler had been performed as infrequently as the above named composers, he would never have joined the canon. Conductors believed in the music and supported it with consistency. And that is what is needed.

For some of the best writing about a number of the composers mentioned, I highly recommend Walter Simmons’ two books on the subject: Voices of Stone and Steel; The Music of William Schuman, Vincent Persichetti, and Peter Mennin; and Voices in the Wilderness: Six American Neo-Romantic Composers (Ernest Bloch, Howard Hanson, Vittorio Giannini, Paul Creston, Samuel Barber, and Nicolas Flagello.

I agree with many of your points. What we forget is that it often took many decades or a century+ for some composers and their music to become recognized and championed by just one or a few conductors. This has happened throughout music history. I do remember when Gerard Schwarz decided to do all-Howard Hanson recordings with the Seattle Symphony for Delos label (including his terrific and neglected Piano Concerto). It will be interesting to see if these composers’ music gets ‘picked up’ by tomorrow’s music directors.

Music Directors are like anybody else; they do the work they will be paid and promoted for doing. Gerry Schwarz took over a decidedly third-tier orchestra in Seattle and patiently built it over 27 years into a solidly second-tier one, while building a beautiful hall and releasing dozens of critically acclaimed recordings, most focusing on the sort of music discussed in this thread. Where is he now?

Your last question is a non sequitur. Gerry continues to enjoy a rich career, and that has nothing to do with his championing core American repertoire.

Further, you will find that a lot of conductors are just lazy in certain ways; it takes a lot more work to prepare and interpret works for which there are no recordings or performing traditions. Many are unwilling to put forth such effort when one can lean upon that which has been done repeatedly, and be propped up by the expected reception of the familiar. Not only is the American tradition not taught in schools, mere curiosity is also a casualty.

Your answer makes my point precisely! Those “lazy” conductors have been elevated in recent years to Big Five music director posts, while Gerry Schwarz’ “rich” career is headlined by a pick-up TV studio orchestra, an obscure music festival, and a titular laureate post in Seattle where he is rarely invited back.

I am not picking on Schwarz here; far from it. I was in the Seattle Opera House when he conducted his very first concert with the Seattle Symphony. I walked out of that concert saying “That’s our new conductor!” And so he was. I’ve heard him conduct live countless times, lived through all his ups and downs with his Seattle musicians, watched him put his stamp on the musical life of my city, and then …. what?

A Dutchman who conducts passably decent Bruckner and Brahms in Dallas gets New York. A French-Canadian who conducts (admittedly inspired) Bruckner in Montreal gets Philly. A Venezuelan who prances around like a fairy conducting something in his head while his orchestra plays something else entirely gets Los Angeles.

Meanwhile Leonard Slatkin – Schwarz’ only true rival when it comes to championing American composers – makes a series of lateral moves: St. Louis to Washington to Detroit. Imagine the golden age that would have ensued had Slatkin been given Chicago when Solti stepped down?

Go on all you want about neglected American composers, but it will always be so until we reward those artists who champion them.

My work is rarely performed, but I don’t think of myself as being “neglected.” Had I positioned myself in a better way and seriously got shafted by the powers that be, I suppose I could feel I was neglected. Instead, I chose to be out of the mainstream many years ago, so if I feel neglected or somehow victimized, it’s my own fault.

Thad: “A Venezuelan who prances around like a fairy conducting something in his head while his orchestra plays something else entirely gets Los Angeles.”

Now now. I’ve gone to a lot of his concerts and Dudamel doesn’t jump around on the podium nearly as much as people say he does. Photo-ops are a different story. He’s all over those.

It’s not just a US issue: 20th century late romantics and neo-classical composers get a raw deal across the board. Roussel, Honegger, Bax, Alwyn, Miaskovsky, Pfitzner, Braunfels, Stenhammar, Dag Wiren, Casella, Malipiero…and many more. All second-rank but very worthwhile talents, all sidelined because fashion is not on their side.

On the other hand, Copland, Bernstein, Gershwin and Barber do not lack performances. Raw genius will out…

We will always disagree about what is “second rank”, and what may be first. As with most things, such speculations will vary with the auditor.

There is not much difference in artistic level between all the mentioned composers.

Many years ago, when I was a teenager, I used to visit the American Library in Grosvenor Square, where they had an extensive collection of LP’s of works by American composers. One could borrow these recordings and I got to know many works by Walter Piston, Roy Harris, William Schuman, Samuel Barber, David Diamond and many others. Many of these works I found very exciting and refreshing, and have managed over the years to acquire CD’s of these works, many on the Naxos label. There is so much very approachable music written in the twentieth century, not only by Americans, but by French, English and German composers which I am sure would find many enthusiastic listeners, if only they were given a chance to hear them. If only there was the sort of music education in schools which I enjoyed as a teenager, there would be a large and receptive audience for a much wider repetoire of music than is programmed in our concert halls today.Instead we are promised an “inundation” of Reich and Glass next year. Please wake me when that tedious 80 th. birthday event is over,

Orchestras’ preference for minimalistic / repetetive new music over traditionalist 20C music is due to the illusion that the former is more ‘contemporary’, while the latter is feared to contribute to the ‘conservatism’ of the orchestral performance culture.

Who was it that wrote something to the effect that some believe that the music which holds the highest truths are the musics that are manifest within the most advanced state of the material? It’s a nonsensical belief that nevertheless has held sway.

Yes, that was mr P. Boulez, but it was a view held by most of the postwar ‘advanced’ composers, under the delusion that there existed something like ‘progress’ in the arts. They understood ‘change’ in style as ‘progress’, but of course this is a nonsensical notion. It is a projection back into history, imagining a ‘line of development’ from Beethoven, through Chopin and Liszt to Wagner’s Tristan, and then via Strauss’ first operas and Mahler’s late symphonies to Schoenberg, Webern etc. etc. and forgetting that Beethoven partially turned back to Bach and Haydn in his late quartets, that Wagner wrote Meistersinger and Parsifal after Tristan, that Strauss turned his back to morbidity with Rosenkavalier and that Mahler always remained thoroughly tonal, also in his most dissonant episodes. Material availabilities extend, which is ‘progress’ in the sense that there are more material possibilities to choose from, but that is not ‘progress’in an artistic sense but cumulative availability. Mozart would have been the most reactionary and conservative composer of all and for that reason ‘irrelevant’, like Brahms, and yet they form an important fundament of the performance culture.

But artists like to ‘say’ things which have not been said before, and when that appears not to be possible, at least they try to say the same things in a different, personal way. The longing to find new expression is, by the way, older than Schoenberg: “Would I had phrases that are not known, in new language that has not been used, with not an utterance which has grown stale, which men of old have spoken”. (Egyptian scribe Khakheperresenb, ca. 2000 BC)

Shifting focus from the performances of the composers listed to the writing styles of today’s composers for a moment of thought. With all due respect to these respected composers of the past, what I am sensing is yet another overlap. Just as the heavily ornamented Baroque style became reinvented in the expansive Romantic period, and the trimmed Classical style which evolved from the Baroque and Rococo periods returned in the Neo-Classical period, and Romantic morphed into the Neo-Romantic style, the Neo-Classical may have been reincarnated into the Minimalist movement, but what of the Impressionist/Expressionist period? Might we now be entering a Neo-Impressionist period of music? Is there a shift away from the ideals the American composers were taught in the 1960s-1990s toward broader use of melodic and harmonic structures yet again turning away from minimalist and twelve-tone techniques? I had this very conversation with one of America’s finest composers, Kenneth Fuchs, whose music is evolving into what I call ‘Neo-Impressionism’. He was taught by composers who adhered strictly to late 20th century ideals of counterpoint, serialism, 12-tone technique etc. He said he and his colleagues were not permitted to leave that style of writing which was the norm. Later in his career as a composer, he decided to break loose and create music which comes straight from his heart, in his own sense of writing style and he gives us exactly that. Are the younger generation composers following suit? I do not know enough of their music to say, with the exception of Jake Runestad who is one of the finest choral composers of his generation and also feels this ‘Neo-Impressionist’ way with sound, counterpoint and tonal palette. Aside from the complaint that the composers in this topic post wrote music not performed enough, my question is, are today’s composers strongly influenced by these composers? For the sake of music history and the future, my question is: which composers of the past 75 years have influenced today’s composers? Leonard Bernstein? (Lucas Richman was his pupil and his own compositional style is certainly inspired by Mr. Bernstein). Stravinsky? Bartok? Barber? Debussy? Ravel? Or the names mentioned throughout this thread starting with the original topic? It often takes decades or a century for some composers’ music to return, thanks to one or two music directors who decide their music deserves to be heard or finds it timely for a revival. Audiences change, so perhaps this will be the case for not only the mentioned composers but many others. For me, rather than look back, I prefer to look ahead and work with our living composers so they can compose music for today’s AND tomorrow’s audiences.

Good questions…. The main problem with today’s music seems to me to be the completely diversified field, in a way as has never been before in history. So much music is now available in terms of recordings and information, which means sources of inspiration of the widest possible range. Maybe that makes it very hard to make choices for composers, especially for young composers. The disappearance of norms creates total freedom but also, randomness. The American musicologist Leonard Meyer suggested in the sixties that the end of ‘musical developments’ from WW II onwards would, eventually, end in stasis, where everything would be possible. This makes it quite hard for players and audiences to know which listening attitude would be appropriate. In former times, there was a tradition, creating a value framework. We have to do without such framework.

Good points, John. For me, it should be based on feeling–all of it. Even which composers and music gets cultivated and sustains interest among today’s conductors and audiences. That could easily change in a few decades, and what happens in the world also dictates much of what’s to come.

I agree that the only workable compass is ‘feeling’, i.e. musical feeling, not the impression that loud brass = expression and drooping strings = sadness. But then you have the strange phenomenon that people, and I don’t mean only listeners, but performers, and programmers, don’t trust their own musical feelings because they have been taught at conservatory or university a certain historical narrative – the ‘progressive’ one. I could fill a book with absurdist reactions on this point. One of the weirdest was the reaction of a German radio programmer whom I had sent a recording of an orchestral piece of mine, which had had some success in France. When I called her, in the background some music could be heard. ‘No’, she said, ‘we cannot programme this because it is not contemporary music. But we LOVE it and play it all the time in the office!’ That was the sound I heard in the background. Similarly, an opera dramaturg told me she truly felt she wanted to do my work, but she felt ‘completely innerly divided’ because her intellect told her that it was not contemporary. These reactions demonstrate that these people have a certain aesthetic idea in their mind of what contemporary music should be, and that is what they learned at school. It is a type of reaction typical of the west however; performers from eastern Europe mostly don’t have this bias since they had much more traditionalist education.

There are a majority of people running the classical music world who think and don’t feel.

Just for accuracy’s sake (and I have a vested interest here as I work for Aspen) Teachout is actually quoting the Aspen Music Festival and School’s President Alan Fletcher, who wrote a fascinating piece in The Guardian comparing the way that Americans treat their Twentieth Century composers with the way that the Brits treat theirs (as in, the Brits do theirs more justice). Aspen this year has a focus on the Twentieth Century American modernists for this reason – including works by Piston, Mennin, Sessions (Gil Shaham has learnt his violin concerto especially for the festival), Harris, Schuman and so on. Fletcher, a composer himself, was a student of Sessions as well as Babbitt and knew Mennin btw. Here is that original Guardian piece that Teachout cites – https://www.theguardian.com/music/musicblog/2016/jun/28/american-composers-neglected-aspen-music-festival-classical

I’m an American composer, have been at it for 40+ years, and compose in a style (neoclassical: ala Hindemith, Stravinsky, etc.) thought to be antiquated, so I rarely get any knocks on my door. Yes, I’m at least 50 to 75 years behind, according to some standards. For the most part, audiences who flock to Reich or Glass concerts tend to be pop music lovers, are not into classical music especially and are endowed with a groupie mentality. I call them “groupies” because many of them place Reich and Glass in the ascended master category (meaning that you better not question anything these composers are doing.) Composers like Reich and Glass have benefited from a very different demographic that normally doesn’t attend classical concerts and seems to be disconnected (or disinterested) in the western music paradigm. In discussing contemporary music, some are apt to say, as the blogger before me stated, “rather than look back, I prefer to look ahead and work with our living composers so they can compose music for today’s AND tomorrow’s audiences.” Perhaps I’m being just negative, but I’ve learned that statements like those don’t pertain to composers like me. First of all, “looking ahead” means what precisely? Are the purveyors (producers, promoters) of modern music trying to set rules for what a future musical/cultural aesthetic will be? Therefor, do purveyors have a hand in selecting what “tomorrow’s audiences” will be listening to? If a group or industry can mold or condition society to “like” certain things, it can stand to make a lot of money.

I blame the lack of a musical culture in America to blame for this. Elliott Carter and Milton Babbitt for my money are the two quintessential American composers that everyone should know. Carter’s Asko Concerto and Babbitt’s Concerti for Orchestra should be staples on the American concert scene. But this would never happen because Americans wouldn’t know good music if it slapped them in the face. I live in a debased civilization here in America. We have no national sense of taste and aesthetic any more. Only in a backwards society can ‘composers’ of the like of Philip Glass and Mason Bates make a living.

Comments like this are among the reasons I will never again purchase a ticket to a live performance nor contribute a dime to support any classical music institution.

Few businesses can afford to insult their customers. Classical music isn’t among them.

Boy, you have one seriously fragile ego.

Boy, you have one seriously inflated but misplaced sense of superiority.

No, just a willingness to keep on learning new things and never take anything for granted. Something you obviously never acquired. Now be a good little philistine and go back to Karl Jenkins.

Considering that in the last couple of months I’ve purchased works by, among others, Arthur Berger, Quincy Porter, Peter Maxwell Davies, John Harbison, David Del Tredici and Bernard Rands, your insult is not only presumptuous but also inapt.

Now be a good little artiste and crow like a rooster on your pile of manure.

1) The comment was about contemporary music, not classical music.

2) Classical music is not a business but an art form, although it is often treated as a business.

Not a business but in essence a charity. The art form is eternal but its performing institutions exist on the sufferance of the public. Continue to insult the public with statements like “Americans wouldn’t know good music if it slapped them in the face” (a not uncommon statement hereabouts) and you will find yourself with neither an audience nor financial support. Try to remember that no one owes any of us a living.

Differentiating classical from contemporary is too black and white. Composers of serious concert music are in essence, continuing with classical traditions inasmuch as they are usually composing for standard instrumentations and addressing ears accustomed to music of that idiom.

Audiences of classical music don’t justify their buying a ticket, arranging a babysitter, dressing-up, investing efforts in the parking of their car, stand in queue, suppress biological auditorial urges, by wanting to experience the same splintered confusion that characterizes modern life:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q_yn0kue0KE

I am going to take a different view of this discussion. First of all, the writing of symphonies as a formal structure started to erode by the 70’s. Young composers, and even established ones world wide moved away and began creating other forms of music. As the remainder of the 20th century passed, there were many successful pieces from Adams, Corigliano, Tower, Rouse, Stucky and many others. Even though these composers wrote the occasional symphony, we do not think of them as symphonists.

But the important thing is that conductors today began play more new music, rather than looking back 60 or 70 years. Many journalists are more interested in the contemporary scene rather than what appears to some as drudgery. The new generation of composers have supplanted the older ones. Much the same can be said in Britain, where it is difficult to find young conductors who regularly program Vaughn-Williams or Tippett Symphonies. Perhaps it is time for a look to the past set of traditions on a regular basis and not just in specialized festivals.

And do remember that most of the great American symphonies were given their premieres by non-American conductors. Ormandy, Stokowski, Kousevitsky and Reiner, to name but a few.

So true, Leonard. The same, I suppose, can be said for concerti for soloists and orchestra, although I may be right or wrong in saying, the tried and true standard works still receive more requests and performances than newer works unless they are cultivated by specific soloists and/or conductors.

Leonard Slatkin writes: “The new generation of composers have supplanted the older ones.”

Unfortunate but accurate.

Especially unfortunate for the older AND unknown composers like myself that have been completely passed over.

Many good points you make, Maestro. Personally, I think that it’s vital we stay in contact with the near past while forging ahead with the so-called “new.” No era should be completely overlooked. What gets me (as a 62 year old overlooked composer) is that “the new generation of composers have supplanted the older ones,” as you say. Not only have I been ignored, I am supplanted. – Franklin Stöver

So many comments – and some real vitriolic ones. Obviously this is an important, and touchy subject. 100 years ago or so I suppose people were then worried about the forgotten masters like Raff. Time is a harsh critic, but usually honest and only the best passes the test. Like so many forgotten mid-19th c composers, many of our good composers from the mid-20th will be forgotten. Some of the music will survive, but not all, and that’s ok. It’s always going to be that way. I regret that the music of Tubin and Schmidt hasn’t made more (any?) headway into the repertoire. Well, thank god for recordings. As James DePriest said to me once, “So much music, so little orchestra time”.

I’m not as confident as you are in the idea that “only the best passes the test.” “Best” is a populist and therefore inept concept. But I agree, as you say, that “it’s always going to be that way” because populist views always win out even when they’re wrong.

I completely agree that what’s popular doesn’t mean it’s the best – but can you name a single essentially forgotten work that is truly great, worthy of standing next to the best, worthy of inclusion in the so-called standard repertoire? I can’t. Not to say that’s there’s not a lot (and I mean a lot!) of very fine music worthy of inclusion in concerts. When I was discussing this issue with DePriest years ago, he summed it up concisely, abruptly and harshly: “There are no undiscovered masterpieces.” I guess this means that posterity is usually correct. The great canon of western classics is filled with music that deserves to be there. On occasion, things get the boot, too. But rarely are things added. No matter I much I love the music of Pancho Vladigerov, it’s never going to be mainstream. How many works written since 1960 have been added to the standard rep? Not many. I truly feel sorry for some of today’s talented composers. They have a tough enough time getting performances of their music, little chance of making money from it, and the sad fact that most of their output will collect dust. Their only bid to posterity will be a posting on Youtube. And yes, populist views are sometimes wrong, especially in the short term. Yet after 200 years, the populist view must have something going for it.

Why yes, I could list many works that are worthy of being classified as undiscovered masterpieces, and indeed, the vital, immediate and passionate voice of Vladigerov could indeed become mainstream if given the exposure it deserves. On a personal note, I’ve played Vladigerov’s two of his violin works (Pesen, and the Choro Op.18) many times now, and their reception is never less than ecstatic.

Your statements will always be a matter of disagreement.

As one example, in 1980 I played Strauss’ Alpine Symphony in the Seattle Youth Symphony. I don’t have statistics, but from what I could tell at the time, the piece had a few recordings but very few performances. Karajan probably helped bring it back into fashion with his 1983 recording. Now it’s played almost as much as Heldenleben.

While I was a great admirer of the late James DePriest, if he said “there are no undiscovered masterpiece,” he was missing the point. The key isn’t “undiscovered” works, but neglected ones. And not everything needs to be a masterpiece to be worth playing. Fortunately he recorded one of my favorite neglected semi-masterpieces: Korngold’s Symphony in F.

Excellent points you make.

If the Italian string ensemble ‘I Musici’ had not dug-up Vivaldi, in the fifties a completely unknown composer from the 18th century, the Four Seasons would never have entered the repertoire and become over-popular. ALl music before Bach was terra incognito, and the efforts of the HIP movement have led to the inclusion of Monteverdi in the repertoire, whose Orfeo and Poppea and Vespers are now a regular treat in music life. 20C music is an altogether different territory, which cannot compare, for many reasons, to either the pre-Bach period of the common repertoire period of 1750-1920. The discovery of Weinberg in the last years has offered some 20C masterpieces indeed. The Berlin chamber orchestra Kammersymphonie Berlin, regularly searching for unknown music from the interbellum, has discovered at least one master piece from the twenties: Ernst Toch’s cello concerto, which they put on CD. Nobody can say there are no 20C master pieces that have been overlooked, if there is no research into the territory.

If Ithe good passes the test of time, that is only possible if there is a value framework in place, a performance tradition which exercises the tests by performance. But that implies aesthetic norms. When these erode, the process of testing erodes as well, there will no longer be a receptive framework, and both the good and the bad and everything in between passes through the indifferent ear without distinction.

Well, yes I can list off probably dozens of works that are as good as or maybe better from the tried-and-true war horses. But here’s a few: Henze’s Der Junge Lord (opera), Busoni’s Dr. Faust, anything by Charles Alkan, Janacek or Martinu, Herzogenberg, Karg-Elert, Skalkottas, Wallingford Reigger, etc. etc. It isn’t a difficult task to do if you’ve paid attention to lesser known composers for a while. This is all so subjective, however, and I’m sure my list wouldn’t look like anybody elses list. However, I’m not sure I would resort to the year 1960, asking if anything good or lasting has been written since then.

It is unlikely that the present programming model will support any rediscovery. MDs schedule their friends and/or themselves, especially with living composers.

Is there a technological workaround? Is there any virtual symphony software that can take a score and create a good representation of it?

Notion 5 is good, but Native Instruments (in beta) is the best I’ve heard. Amazing actually. But still, the real orchestra must always remain the ultimate experience for composer and audience alike.

“But still, the real orchestra must always remain the ultimate experience for composer and audience alike.”

In our modern world, that view will not be shared by everyone. Over a decade ago, when I first got into classical music filesharing, I discovered that a lot of fellow classical fans preferred listening to MIDI versions of classical piano repertoire, since the rubato and other “interpretative” aspects of live human performances annoyed them, each particular performance sounding like a different flawed version of the “pure” music they heard in MIDI files. I wouldn’t be surprised if some people today prefer synthesized orchestration, which is after all increasingly used in film scores and musicals.

I agree. Live streaming and high quality video archives at reasonable prices have led me to cut back on concertgoing.

The virtual orchestra approach is definitely limited and won’t help a lot of the composers we’ve been discussing. Their works are still under copyright so getting access to them and into the software won’t be easy. But, living composers could self-publish. It won’t generate a living by any means. The only reward will be that a few people would have the chance to hear it.

The art of orchestration, or rather the skill required to bring out a masterful orchestration (that musicians can actually perform) can get lost in virtualizing everything, especially in the hands of neophytes who could care less that a violin can’t play low F# below middle C. So, for those composers who actually care about what they’re doing, a performance by live (professional) musicians will always be the greatest treat. I would rather annoy a handful of ignorant listeners than neglect tempi markings set by the composer. If they want machine music, there’s plenty of it out there.

“…especially in the hands of neophytes who could care less that a violin can’t play low F# below middle C.”

Electronics have been used for decades now to create virtual instruments capable of playing pitches outside the range of the “real” ones. (Ever hear George Benjamin’s Antara, for instance?)

“I would rather annoy a handful of ignorant listeners than neglect tempi markings set by the composer.

You don’t understand. A properly created MIDI version of a work is guaranteed to preserve the tempi markings set by the composer. It is human performers who might stretch and bend the composer’s indications in the name of interpretation. That niche of listeners who prefer piano works in MIDI form are sometimes not at all “ignorant”, but in fact possess a knowledge of the work’s score.

Christopher Culver: “…Over a decade ago, when I first got into classical music filesharing, I discovered that a lot of fellow classical fans preferred listening to MIDI versions of classical piano repertoire…”

Interesting. How does this work in practice? I downloaded some classical piano MIDIs and they sound tinny on my Mac regardless of which type of piano I select on the player. Does one have to interface the computer to a good electronic keyboard or synthesizer to properly play the sequences?

If you’re fluent with Finale, it works in conjunction with Garritan Personal Orchestra. While not the absolute best of the virtual orchestras available, it is more than merely good; using that I’ve been able to hear things such as Leo Sowerby’s 5th Symphony, Henry Hadley’s Symphony No.5 “Connecticut”, and many other works that would otherwise have remained on a live performance wish list.

I think I know what I’m talking about here. I worked in an electroacoustic studio in the 1970s in Utrecht and have seen a lot of change. However, for personal and artistic reasons I prefer to rely more on more own my own native ability and no so much on technology. And I don’t care about expressing only one tempo.

It is amazing that none of the respondents here mentioned either the symphonies of Elie Siegmeister, Morton Gould, Irwin Bazelon or William Grant Still as worthy alternatives. Some of you may think little of any of the composers I have named, but I have found their work to be some of the finest American music composed during the same time as Mennin, Piston and Schuman, the latter who I find to be the most overrated American symphonist, even though I do like and admire his fifth and ninth symphonies. But there is a gold mine waiting for those who’ve never heard Siegmeister’s second or fourth symphonies, Gould’s first and third symphonies, or the second and fourth symphonies of Still (Most everyone knows Still’s first, the celebrated “Afro-American” Symphony).

Furthermore, the symphonies of Bazelon, while rough in idiom, are still highly communicative works that deserve to be programmed more often. Yet one symphony that is rarely heard in the concert hall is Bernard Herrmann’s sole symphony from 1941. Since its premiere, the work has only received a handful of performances, the last taking place in Seattle almost a decade ago. This is a symphony that can stand tall alongside the other American symphonists mentioned in this thread.

And for those who knock Carter…how many of you have ever heard his first symphony from 1943, or the Holiday Overture from 1944? These are works written in the same populist Americana vein as those of Schuman and Piston, and can be discussed and compared alongside them without prejudice.