Can you record a full orchestra with a single microphone?

mainApparently, yes…. although I don’t get a full, close sound picture through my headphones.

Others may hear it differently.

The device is called Zylia.

Apparently, yes…. although I don’t get a full, close sound picture through my headphones.

Others may hear it differently.

The device is called Zylia.

Anna Starushkevych is a Ukrainian-British opera singer who…

This is Deutsche Grammophon promo for her forthcoming…

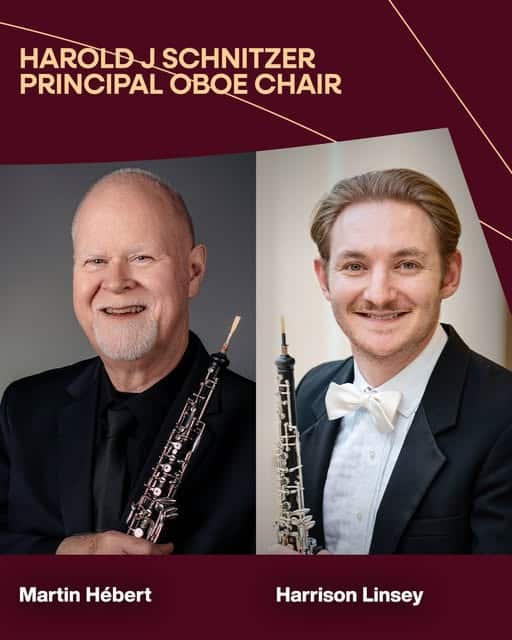

Martin Hébert is stepping down after 19 years…

Metamorphosen, for strings alone, contemplates the world after…

Session expired

Please log in again. The login page will open in a new tab. After logging in you can close it and return to this page.

Comments