Can an atheist play Messaien?

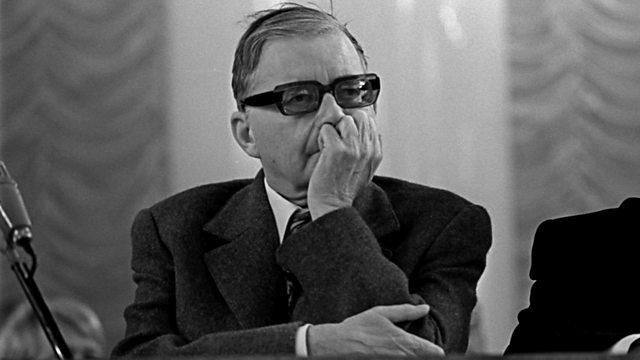

mainPaul Jacobs, chair of the organ department at Juilliard and a Grammy-winning Mesiaenist, takes a broad view of faith and the act of performance. But he believes that listening to Messiaen could change your mind about the big questions of life and death.

Messiaen’s own beliefs are grounded in a collective worldview that has endured for 2,000 years, inspiring some of our greatest art, literature, and music. Of course, one doesn’t have to accept this worldview, but perhaps it shouldn’t be dismissed as inconsequential to us, either. It might serve as a critical gateway to a deeper understanding of the human condition….

It would be shortsighted to value Messiaen’s music merely for its aesthetic appeal. After all, his professed objective was much grander than this. He longed “to express the inexpressible,” “to touch upon all subjects, without ceasing to touch upon God,” and, by extension, to inspire us to do the same. Messiaen’s message is delivered with a crushing majesty, much like Bernini conveyed in his sculpture, The Ecstacy of St. Theresa.

Our plight is that the hectic, noisy pace of contemporary life drowns out the silences of Heaven. We’re addicted to technological contraptions, enslaved by hyper-busy lifestyles, and endlessly pursue mindless diversions and entertainment, all of which numb us from reflecting upon the most marvelous things. But, just maybe, the shimmering light of Messiaen’s music could move a person enough to investigate the Numinous.

Fascinating interview in San Francisco by our friend, Elijah Ho. Click here for more.

You might also ask: Do you have to be a Pietist Lutheran to play (or sing) Bach?

Exactly.

Good music is good music, and I would expect capable musicians to play it well regardless of whether s/he shares the composer’s religion.

It works in reverse too. Many composers (e.g. Ralph Vaughan Williams) write enduring sacred music even though they are outside the faiths for which they write. Today the tradition continues, with John Rutter, an agnostic, writing the most loved and frequently performed modern sacred choral music.

Next question: Could a Catholic cellist really play Bloch’s Schelomo? I’m on the edge of my seat.

While I don’t believe you need to be “Pietist Lutheran to play (or sing) Bach”, I would argue that a Christian might understand the meaning behind a hymn like “Amazing Grace” more deeply than someone to whom the lyrics are simply words and not faith. Likewise, a person of Jewish faith might experience works on the Holocaust more deeply than others, or a Chinese person might understand works about the Rape of Nanking more deeply.

It isn’t to say that you must be Catholic to play Messaien, but certainly it isn’t rocket science to understand that if the work was written by a devout Catholic to honour his faith and God, then someone of that same faith would understand it more fully than someone who is not of that faith.

The interaction between aesthetics and religious belief is something which has interested me for a long time. Max Liebermann made the famous observation that a well painted head of cabbage was worth more than a badly painted head of the Madonna.

Personally, I am an atheist, and, culturally, I am a Catholic atheist. Despite the fact that I have no belief in God, because of my cultural background, and the memory of my religious beliefs, Messiaen’s “O Sacrum Convivium” is capable of touching me in a way in which I could never be touched by something very Anglican, such as Herbert Howells’s “Gloucester Service”. As for “Amazing Grace”, it doesn’t really do anything for me at all. As an Englishman and a Catholic, this hymn has never been something of which I have really been aware, culturally or religiously. Of course, I know the words and the melody, but only in the way in which I know the words and the melody of, say, “The Star-Spangled Banner”. As music in itself, I would say that it is of negligible quality, just as I imagine that an American or a Protestant would consider “O Sacred Heart, our home lies deep in thee” to be of negligible quality. Indeed, it is of negligible quality, but if you are an English Catholic you will probably have fond memories of a time when you once sang with conviction, “O Sacred Heart, bless our dear native land”. Even now it makes me quite nostalgic for the idea of the conversion of England! The point is that I think that Liebermann is wrong. If you are a Catholic even the worst head of the Madonna has the power to arouse feelings that could never be aroused by the finest head of cabbage.

On the other hand, that is a discussion of “good” and “bad” art. My director of music at school (an atheist of seemingly no religious sentiment whatsoever) used to say that he didn’t know what was the greatest cultural achievement of human civilization, but it was either the “St Matthew Passion” or the “B Minor Mass”. I would be tempted to err on the side of the “St Matthew Passion”, a work which I have both heard and performed, and I would say that my hearing and my performing were neither diminished by my being an atheist of Catholic background nor enhanced by my having at least some Christian background. Perhaps what I am saying is that music of a certain quality has the ability to transcend distinctions such as belief and unbelief.

As for Messiaen, I only quite recently discovered the “Vingt regards sur l’enfant-Jésus”. No, I do not share Messiaen’s beliefs about the infant Jesus, but that is not to say that I am unable to appreciate a quality in the music itself which could, perhaps, be called divine.

I don’t think there’s anything novel in saying that music evokes the transcendent, whether or not you adhere to a religion.

Below are some cogent thoughts on the matter–and on composing sacred works–from John Rutter, whom I referenced above. The source is a fairly recent Limelight interview (link below).

In order to write sacred music, does a composer have to be tapped into the spiritual? Is that a necessary part of your process?

You certainly have to have a sense of faith. That is not usually difficult for a musician, as musicians move easily in the realm of the mysterious and the transcendent. I don’t think it matters whether you are a signed-up believer of one particular faith. I was asked very specifically when I did this album, to include at least one or two of my sacred pieces as transcriptions without the words so people could enjoy them in a different way.

Are you a practising Anglican?

I am a reverent believer at the time I am working on a sacred piece. When I take a sacred text I believe every syllable of it while I am setting it to music because I think it’s part of an artist’s job to enter into states of being which are not necessarily his or her own. As long as I’m writing or conducting I am a firm believer and when I have finished I go back to being what I am the rest of the time, which is Agnostic.

See more at: http://www.limelightmagazine.com.au/Article/329417,john-rutter-an-agnostic-speaks-out-on-writing-sacred-music.aspx#sthash.Xr6HAsfG.dpuf

“Agnostic” is a matter of degree and occasion. As Isaac Watts wrote in his great hymn, “Give me the wings of faith”, even the saints “wrestled hard, as we do now, with sins, and DOUBTS, and fears.” To be sure, great composers as unabashedly orthodox as Bach and Messiaen are in the minority. Far more would raise eyebrows if pressed to articulate their faith in words. And I think it is of their glory not to cede such primacy to any verbal statement. How dare any grand inquisitor imagine, for instance, that by getting two people to say “I believe in God the Father”, he has gotten them to state the same belief?

But even fewer have been atheist.

You don’t have to be a catholic or even faintly religious to appreciate that Messiaen’s music puts us in touch with ideas and beliefs that are far bigger than we are. It’s spiritual rather than religious. I feel the same when I hear or play the music of Takemitsu. Or Bach. Some might even argue that Brian Eno’s Apollo has a similar effect.

Do you have to like Bach if you’re a “good” Lutheran?

Do you have to be a shifty sensationalist to appreciate Norman Lebrecht?

I remember asking a Jew who shared the platform with me many years ago in a performance of Verdi’s Requiem. I also asked this question to my head of singing at the Royal Northern College of Music. Both said, as prominent professional singers of their time and of much Christian vocal music as well as the wealth of other vocal music, that you have to believe in the music there and then as you’re learning it and performing it, and put yourself into the shoes of a believer, otherwise you are a fake. Being pious anything was not the answer. Nothing worse than a layer of piety hanging over religious music. It’s always getting under the skin of the composer, what HE believed in, and taking that on board – becoming the character for that space of time. Otherwise don’t play or sing it was the advice I got over the years.

Never an easy composer to spell…

I’m tempted to point out that Mr Jacobs is taking anything but a broad view of faith and performance. Nobody would possibly argue that religion didn’t have a major effect on human history for the last few thousand years, but it doesn’t therefore follow that you need to believe it to understand and feel the power of civilization’s great achievements. I have nothing new to say, but am adding my voice to the non-believer side here: like some others who have written in, I’m both a passionate atheist and a passionate musician. Disbelief in god doesn’t prevent me from having a transcendent experience whenever I conduct a Mozart opera or a Bach Passion, or from trying to get inside both composers’ minds. Indeed, to quote The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, “isn’t it enough to see that a garden is beautiful, without having to believe there are fairies at the bottom of it too?”

When Mr.Jacobs compares music to painting one comes away with the thought that in making the comparison he doesn’t fully understand either discipline well enough to

comment on them however he poses himself as a “thinker”.

His take on the Bernini as crushing majesty is almost laughable . All art is about itself .

Music is the most abstract of the arts and has no meaning except sounds arranged

in a fashion that suits the composer .Without the mystique of the Messiaen name

and religious belief attached to his music it is just ” abstract sounds ” put together

that the composer hopes will please the listener .If that fails we then touch upon God ,

life and death and whatever else catches our fancy. When you get to the silences of heaven bit ….you wonder at the sort of teaching goes on at Juilliard.

Making music is quite similar to acting. You certainly don’t need to have committed a murder yourself to play a murderer. But if you are unable to feel yourself under the skin of the person you are representing, your acting will be shallow. As a musician one has to be able and willing to feel one’s way into the work, religious and philosophical aspects included, but one does’nt have to share them in one’s personal life. I think the idea that a shared religion makes you a better interpreter of the works of some composers has not more truth in it than the popular notion that musicians must by birth have a deeper understanding for music written by composers of their home country.