Too many nearly-good pianists are ruining competitions

Comment Of The DayReader’s Comment of the Day comes from David R. Moran, in reponse to Israela Margalit’s virally-read Confessions of a Competition Judge:

The real and intractable issue is there is way too much near-goodness. Mostly second-tier, but real goodness nonetheless.

What is to be done? This wrenching writeup in the end avoids the serious practical questions. The classical world is overflowing with gifted musicians, technically and interpretatively excellent in any sense. Some of the (also) lucky best do become regional lights. A very few go on to wider, even global careers (some of those unworthy in other respects, but showy or novel or whatnot). Yet most not. Caprice and luck are a big a part of it, arguably too big.

So what instead of competitions? I (not in NY) hear and sometimes review a large number of high-caliber young pianists every year. Third prize at this or that. What sort of future awaits them? Teaching and local recitaling, with some touring. Then academe — if they are lucky. Teaching the next. Many play more satisfyingly than the big names of their cohort. (Sez me, meaning to my ear.)

Not clear to me that competitions make the situation better or worse. (IM’s corruption report is beyond disturbing; all this has to be a good-faith marketing effort.)

Regardless, there have to be filtration and trial processes.

Yes we know there is a problem, and the problem is constantly stirred up.

But no one proposes a good solution. Anyone? Anyone at all?

I mean, ‘there have to be filtration and trial processes’. Great. I agree. But what do you have in mind?

Sorry, I don’t understand this comment. What exactly is the statement it makes? What is the response to the article by Margalit?

Yes, it seems like a stream-of-consciousness writing — not particularly helpful or useful.

Perspective is something that can only happen when we take an overview of a situation. Competitions are, basically, for the very young. These musicians, whether piano, violin, cello, conducting etc, have been trained in repertoire, most of which is similar to each other, and they have not lived long enough to let this music ‘marinate’ inside and they have not yet lived life long enough to reflect the music as we know it. The public has also been fed numerous recordings of the same repertoire and come with an expectation of the level of playing and sound delivered by these young musicians. Competitions are basically, if viewed this way, a breeding ground for many colleagues to meet, and, should any walks away with ‘prizes’ or possible future engagements, that’s all well and good. The real prize may be that they have challenged themselves to be not just good, but as great as they can be for this moment in their lives, to meet friends, make new friends, be seen and heard and use the experience as a stepping stone in their ‘yellow brick road’. Competitions do not make careers. What these young artists do well into their 30s, 40s and beyond is what makes their lives and careers in different ways. There are no substitutions for living. We can’t expect someone to reflect life through their fingertips playing certain music if they have not yet lived through that emotion or experience. Everything exits through the fingers. Have we come to expect too much, too soon? Is too much pressure put on the young musician, for example, ‘if I don’t win this, I’m finished’ syndrome? There are many ways to make a life in music. These things take time, imagination, life, trials and tribulations. And, if for those who win, they create unique opportunities for music in which they take music to different avenues, and themselves, that is a good thing.

To put this in a context that perhaps only some Americans (and of a certain age will grasp) the point is that in order to have the Harlem Globetrotters, you need to have the Washington Generals, a basketball team which existed for the sole purpose of being beaten. In order to have Jack Nicklaus, you needed to have Tom Weiskopf. Cannon fodder.

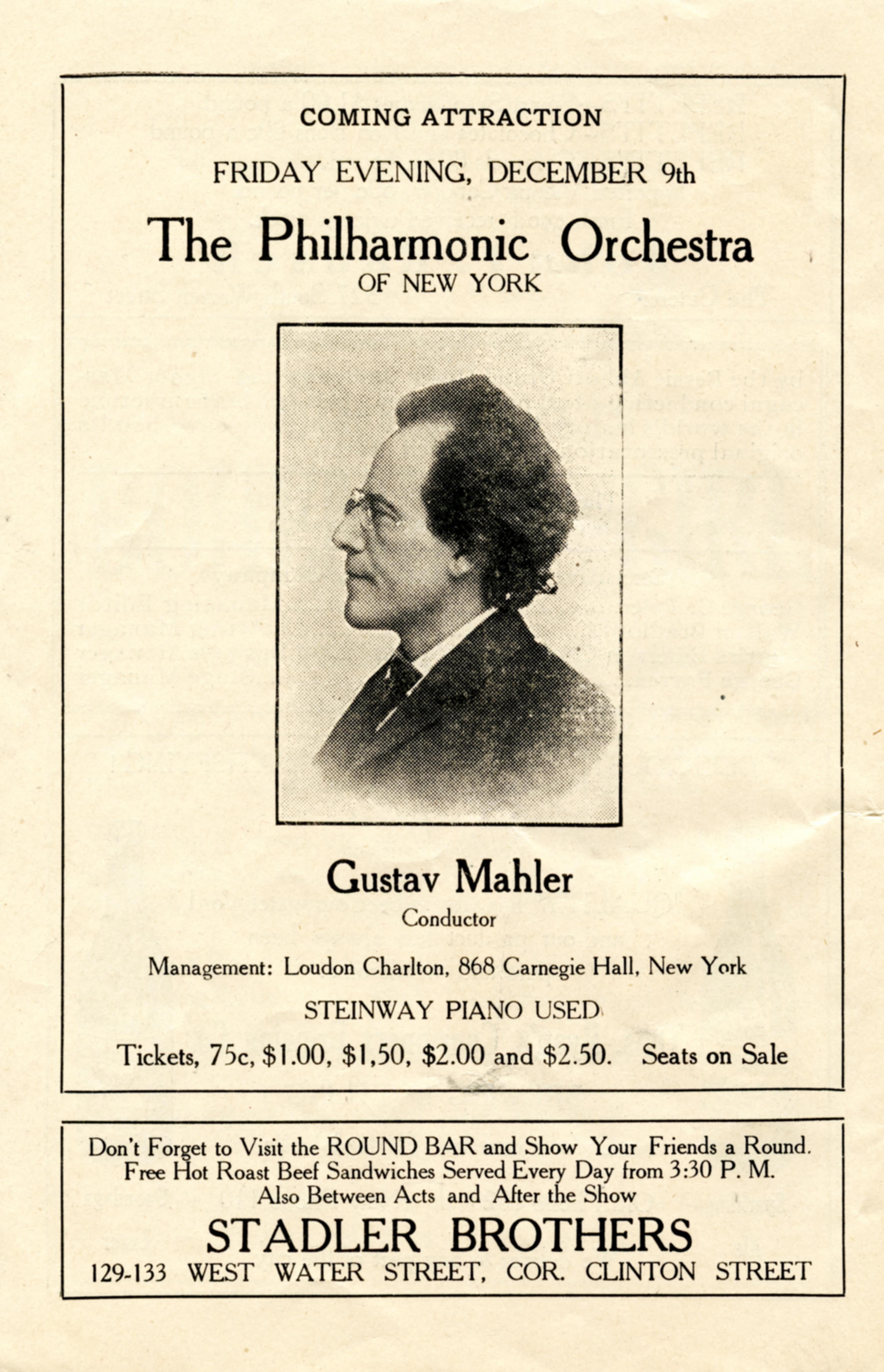

I knew a very good pianist with fine teachers, who won a respected competition (the Dimitri Mitropoulos), made the LP recordings of Liszt and Rachmaninoff which were the main prize and then … crickets. She was good friends with Eugene Ormandy and once dared to ask him why she had not been engaged or re-engaged to play with the Philadelphia Orchestra, and she related that Ormandy was shocked: “But Martha …. pianists are a dime a dozen!”

Sobering. Mischa Elman put it differently — when asked to comment on why there seemed to suddenly be so many wonderful violinists, he responded that the level of mediocrity had risen tremendously during his lifetime.

Come again? What is the problematique here? Is this person trying to express the frustration of highly talented musicians not finding appropriate channels of expressions? But what do filtration and trial process have to do with that?

Put me down as another reader not understanding this person’s comment. The idea is that there are more almost-top-tier musicians than there used to be? And the competitions aren’t doing enough to identify the “greats” from that group? So we need a non-competition filtering mechanism to identify them?

Hardly clear to me that a kingmaker imposing his own tastes will do any better to rescue the “deserving” from the pool of near-greats than competitions do.

Or is he merely saying that it’s a shame that third place at the major competitions frequently turns out to be an extraordinary musician but they get popularly ignored for not winning gold? If so, well, sure, but I think that’s always been an issue.

Le mieux est l’ennemi du bien. (Voltaire)

I can’t quite tell if these mostly useless handwringing or flip responses are in response / non-response to what I wrote, even as what I initially posted was hardly unlike them.

The Washington Generals thing is silly. The kids have to make a living in their 20s, as young adults in their 30s and beyond, somehow, of some sort.

One (not that important) point is that IM’s 2017 article itself is kind of useless, apart from her shocking corruption report. (Maybe it’s good to be totally cynical these days about everything musical, same as everything else. Useless, but fun and feelgood.) Yet she offers no more than what I am accused of not offering. (If I’m understanding the comments.)

It might be helpful to talk to the kids themselves and their parents. An *SD* feature assignment! What do they see, what are they told, what are their plans, upside or downside?

Eric Lu, George Li, Larry Weng, Alex Beyer, Charlie Albright, Niu Niu, Conrad Tao, VKholodenko (he’s a little older, like Grosvenor and Trifonov and JWang), Artur Haftman, Peter Fang, Haochen Zhang, … Buniatishvili, de la Salle, Jan Lisiecki, Hsiang John Tu, Yue Chu, Han Chen, Sa Chen, Xiaopei Xu, Tony Yike Yang, and so many others I am leaving out.

I have written at length about almost all of these recently, some of them more than once.

Does it matter what I find lacking in Grosvenor or Trifonov or JWang or Tao? Not at all. George Li? Nah, not by now.

What I write about Andrew Li, on the other hand, sure. PKolesnikov and PFang and Haftman and Beyer, maybe.

I am not a reviewer in an important venue by any stretch of the imagination. I personally think you should not miss Niu Niu ever, but does that matter in the big scheme of things?

What are all of these capable pianists on the lower tier — and they are the intersection with the Boston area only! — going to be doing for folding money in 5 and 10 and 15 years? No one knows. Do competitions have a role? They have to, no? Or is it just to be left to the capricious courts of public and managerial and journalistic opinion, with parental and teacher lobbying?

I believe, au fond, that there is no better way that is feasible and financially viable than some sorts of competition and public hearings. Let someone with other concrete ideas step up now and not just post equivocal handwringing.

All good points. However, having lived through winning some competitions, what I have personally experienced to sustain a career is simply a yellow brick road journey. The competitions can be helpful – even for many who do not win. There are new friendships made, and repertoire mastered at that stage of development. There are presenters who take a liking to performers whether they win or not. I’ve seen that happen many times. Careers build over long periods of time. Everyone has to follow their own yellow brick road. For me, playing traditional repertoire and recording some have been part of my own evolving career, but most importantly, because the music means something significant and there is something else to say about it (e.g. for myself, these include Bach and Mozart recordings). Everyone has to follow their own voice. For me, friendships with living composers slowly evolved. True, we can’t ask Beethoven questions, like, “Would you edit your dynamic markings on a modern piano?” But, in the process of commissioning music, one can ask a composer any questions and also add to the repertoire for the future. I’ll never forget when one of the most powerful artist managers once said to me, “Make friends in the business.” What she was trying to say, was, don’t sit back and wait for things to happen. True, playing a wonderful performance of a Beethoven sonata is fulfilling on every level, yet, for a career to sustain, there are other waters to navigate to keep the ship sailing. For me, I turned to the future to sustain the present, and, in the process, have seen many new places and helped bring many new and wonderful concertos to the repertoire for piano and orchestra, and piano, orchestra and chorus. Was this planned? No. Was this thought of after winning a competition? No. It stemmed from encounters with many composers from the age of 12 onward. Many musicians might soul search, discover the seeds which had been planted, and follow that muse. This far outlives a competition win

People commenting on this thread need to have read the “Confessions” article that this is about. Some commenters appear not to have done, and so their comments are necessarily unhelpful.

There is not just one problem, and maybe it might help to look at them separately?

For example:

1. Musicians need to learn a living, but there is limited room at the very top of the profession

2. For a variety of reasons the best folk don’t always win competitions.

One of the solutions was in the article, that is, not to allow oneself as a performer to be defeated by an unfavorable result or review, but to press on, and even if successful in competition, not to rely on that but use all channels available to you to develop your career.

Also, please don’t stigmatise teaching or Academia as second best! It’s an entirely valuable and important part of the profession, and easy to earn a living.

If classical music has value, that value does not lie solely in being at the top of the performing tree does it?! That kind of thinking is part of the problem, in that it denigrates the non elite music making which is in fact the bedrock of the wonderful art and joy of music making. And it confirms the charge of elitism.

The lack of value given to amateur and non-pinacle-of-the-profession classical music making is the biggest threat to Classical music’s continuance, and the sooner we bin that thinking, the healthier the classical music world will be.

J.S. Bach didn’t expect to be a superstar. That wasn’t his motivation! He loved music for itself, and as an expression of what he believed in.