Pierre Boulez, five years on

mainNinety years old when he died, five years ago today, Pierre Boulez was the dominant creative musician for more than half a century – dominant not so much for what he composed but for the doctrines he insinuated and imposed.

He was the most articulate of modernists, the most persuasive of atonalists. He could persuade you in the same breath that the future of music would be mechanical, and that it would be orchestral.

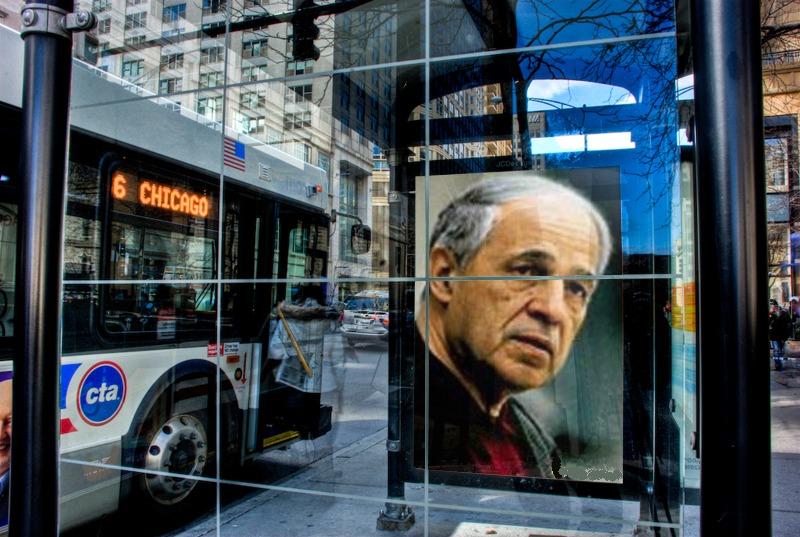

He was a man of immense charm, infatuated with his own power. His image was everywhere, in Berlin, Paris, London, New York and (below) in Chicago bus stops.

Five years on, who speaks of Boulez?

Five years on, who speaks of Boulez?

Thankfully no one, the guy already had too much space.

Along the same lines is this fascinating article by the noteworthy young composer Matthew Aucoin. It was published in the November 5, 2020 issue of The New York Review of Books. Link is below, but it is behind a paywall.

If you deliberately compose music that is not designed to ingratiate or communicate to a non-specialist, intelligent, lay listener, who is willing to listen until he or she is pushed away, this is the result. The same is true of Schonberg, whose 150th (!) birthday anniversary is coming up in 2024.

https://www.nybooks.com/articles/2020/11/05/pierre-boulez-sound-and-fury/

As a composer Aucoin is nothing to write home about.

Nor as a commentator on his elders and betters. The NYR’s standards have slipped since such a book might have been reviewed by Charles Rosen or Joseph Kerman [alas, both deceased].

I’m not going to pay for an article on PB.

Some of Schoenberg’s music has become part of the repertoire, that is: the early tonal works, and the expressionist dark works, which still hint at musical processes and are therefore still expressive (like the Five Orchestral Pieces and the short opera Erwartung). When he began to write 12-tone works, he fell of the cliff into the sound art territory, which is an art form different from music, or it is a mixed form, part music and part sound art, an imitation of music with all the wrong notes that are carefully avoided in musical works.

What tosh.

A typical reaction of people who [redacted] and [redacted], for which there is a word, which is unprintable, because it is [redacted].

From discussions on classical music fora and Boulez listeners on Last.fm, it can be seen that many or even most fans of the composer are non-specialists, not involved professionally in avant-garde music at all. They simply like the way the music sounds. A common trajectory seems to be e.g. a person getting into Ligeti through the *2001* soundtrack, then moving on to Boulez and other Darmstadt composers.

Boulez certainly remains a niche interest, but I wish we could stop with the suggestion that the music only existed for Boulez’s peers. And Boulez’ interactions with French schoolchildren show that the composer himself was grateful for interest from the untrained general public.

It’s cold and gray outside. I’m in the mood for one of his clinical and forensic Mahler-as-Second-Viennese-School recordings!

Me Too!

Sally

‘Infatuated with his own power’?

I don’t think so.

A great musician. He is sorely missed.

Oh!

“Five years on, who speaks of Boulez?” The people who miss his integrity, musicianship and vision?

Hear hear !

Denigrating comment from Borstlap in 3… 2… 1…

LOL

Yes, Mr Borstlap does seem to have a fixation with Boulez.

I would never hurt anyone’s feelings unintentionally.

Which, according to many sources, puts you in line with any number of soi-disant wits, among them Wilde…

Maazel, who was not reputed for his indulgence, considered conductor Boulez as “poorly gifted yet insanely competent”.

Strange comment. Poorly gifted in what respect?

Let’s say “averagely gifted” i.e. the contrary of born-conductors such as Reiner, Celibidache, Karajan, Kempe, Maazel, Rozhdestvensky, Muti, Ozawa, Levine… Boulez compensated by his analytical skills and pragmatic solutions. For sometimes stunning results.

Sounds like an autistic car mechanic.

I heard a big orchestral composition by Maazel that made Boulez’s music sound like Offenbach. Talk about the pot calling the kettle black.

Barry,

Nobody tries to claim that Maazel was a great or important composer.

However there are hundreds of poseurs who claim that Boulez was a great and important composer. Most of these people would not recognize any of his compositions out of the blue, do not listen to his music in their spare time, and loudly praise anyone who programs/plays his music (making their numbers seem larger and more enthusiastic than they are; while possessing no knowledge of whether the performance was good and even 50% of the notes were correct or not). Poseurs.

I could definitely name some of Boulez’s works on a ‘drop the needle’ test – certainly not all of them. And I’ve been called far worse than a poser (I like my spelling of it).

Ps: what is the source of this quote?

I think more people still speak favorably of Boulez now than ever speak of Maazel one way or the other.

Sure, but let’s face it, history has already forgotten Maazel. Boulez, on the other hand, will be remembered for a long, long time. Perhaps not so much for his music, but for his polemics and what he stood for in general.

So said the man who single-handedly tried to destroy the incomparable Cleveland Orchestra with directions to arbitrarily change notes because they “sound beautiful”.

The patterns of this Pli are beautiful, who would deny that?

But they don’t mean more than that, beautiful patterns, subtly polished. And rather boring after a while because rather bland. And extremely boring after an hour for the same reason. It is not something to listen to in a concert hall, but at home, daydreaming or making tea with an electric water boiler making an acoustical contribution to the setting.

And the patterns are static, anything can happen or not happen at any moment, randomly, like riples in water.

It’s not so strange: in the visual arts, or architecture, there are also beautiful abstract patterns, like the decorations of the walls in the Alhambra:

https://www.piccavey.com/granada-alhambra-walls/

But claiming that this is a normal, progressive development of the musical tradition is nonsense and irredeemably pretentious and totalitarian; that was the big mistake of PB, not to speak of his ridiculous other claims.

“For nervous, anxious people, or people suffering from insomnia, pieces like Pli selon Pli offer balm to what has remained of their soul.”

http://subterraneanreview.blogspot.com/2016/01/notes-on-boulez.html

well, too many people are speaking of Miss Hannigan. that s the real problem.

She does a marvellous job in the video, trying to make it expressive.

I do. I was his Yniold in the legendary ROH production of Pelleas et Melisande with Elizabeth Soderstrom, George Shirley, Don McIntyre et al. Shortly after his provocative Der Speigel article where M Boulez advocated blowing up the opera houses he came to the Garden and – long after, I discovered that the deal breakers were a week of orchestral rehearsals in their summer break and – for the first time – a boy treble Yniold. He got both – and I had the most wonderful introduction to the highest levels of music making from a warm, witty and utterly supportive genius. Subscribe to http://www.theartschannel.online and watch a wonderful film about M Boulez – or take my word for it – he was the real deal.

Can’t argue with that.

Well, you could at least try.

Firstly, Tony, fascinating to hear your memories of singing Yniold with Boulez. How lucky to have been part of that production! I got to know the opera through that recording and love it (and your performance). Coincidentally I recently found on eBay a reel-to-reel of the original Radio 3 broadcast – at least, I hope it is, I’m still trying to get it transferred – I’d be happy to share it with you, if you’d be interested.

Secondly, just a reminder of some of Boulez’s other achievements. On the subject of opera, apart from the Covent Garden Pelleas, he was responsible for a number of other opera productions, which were unusually successful marriages of music and theatre: the Bayreuth Ring, Paris Lulu and Aix House of the Dead (with Chereau); the WNO Pelleas and Amsterdam Moses and Aron (with Stein).

As a conductor, he founded two ensembles, the second is which is still going strong. Although not all repertoire suited him (true of all conductors), he was exceptional in the repertoire which did. I never found his conducting cold in the many concerts I attended. Equally important, I think, was his influence on approach to programming on the next generation (Rattle, Salonen etc). I was surprised by someone’s reference to the BBCSO not liking him. Nicholas Kenyon’s book suggests that he was very well-liked by them. With the exception perhaps of the NYPO, that seems to have been true of his relationships with most orchestras he worked with regularly. Have a look at the tributes on the Cleveland Orchestra website.

He was one of the driving forces in getting the Philharmonie in Paris built. He founded the Lucerne Academy and promoted educational projects throughout his career. He was a prolific writer. As for his music, I’m not a musician, I’m a lay listener, who has never been repelled by it, as some others clearly are. I’m not fond of the early, very strict serialist works, but love much of the later music, particularly pieces like Domaines, Rituel, Repons, Notations etc. I see from his publisher’s website that his music is still performed quite frequently, certainly by comparison with quite a lot of other composers of that generation.

As for the question, who is still talking about Boulez? I would have thought the answer is pretty obvious: we are.

A-No.1 wrecker, hounder of us old-folk from the concert hall, eminent pied-piper leading aspiring composers into the roach-motel of the academy, from which they would not nor will, ever emerge.

The guilty parties in all this never acknowledged the fundamental difference between performers — many of them — and audiences, most of them. For skilled musicians a new score can constitute a challenge to their resources of technic, sight-reading and so on, and guessing at the composer’s game so as to be able to participate. Professional musicians tend to have special qualities of pattern-recognition and memory, also, as well as a deeper attraction to music in its many guises; this is a function not of culture but differences in neuro-biology.

We chair-fillers show up instead to be delighted, consoled, reminded — those sorts of things. It has derived from 500 years’ worth of tradition leading to and into, tonality and melody. Instead we have been unwillingly subjected to increasing quantities of new music’s long long minutes, which we generally experience as insults. I think it was the Beatles who taught my generation that pop music could be enough. Certainly it got inside our heads, changed us as they were changing, and helped connect us to one another.

The proper venue for the new “contemporary classical” stuff would have been somewhere underground, where it could have attempted to build its own audience and its own patronage. Instead it hijacked the classical infrastructure, halls and state & institutional funding and audience included, hectoring us as we fled and serving up the present desolation, not including an overlay of germs now ending any inertia that’s been keeping the whole thing (just barely) alive.

Embarrassing to put it so bluntly but that’s how it feels to me, after years of trying to be more of a Hep Kat. The one good effect has been 70 years’ refocus on the the Baroque. The future of classical music has truly been its past. (Martinu excepted.)

Its past can also be its future, like the digging-out of pre-Mozart music with all the riches, like Monteverdi who has become part of the regular opera repertoire. Artistic traditions can simply be revived, as happened quite some times in the past, and which is now happening quietly with music – and that has already been going-on for some years. Modernist ‘music’ has already formed its own circuit, and the few times it has encroached upon the classical concert circuit it was out of a feeling of obligation or from the usual misconception of programming staff. It has never threatened the classical concert circuit, which is suffering much more from the accusation of ‘irrelevance’ to modern times – especially from the wokies who see in it a symbol of ‘white supremacy’. Classical music as a practice is something different from classical music as a creation, and as such it has gone underground but at some stage it will surely appear again.

https://www.amazon.com/Surprised-Beauty-Listeners-Recovery-Modern-ebook/dp/B01F9GV8K0

@John Borstlap

You raise many points that raise too many more for the moment, and some being squished together, it’s specially a chore; but let me just ask: what is so sacred about the sonata form? It leads to long works in which appreciation of development and variation requires far more audience understanding than exists today, when almost no one plays and even fewer can read.

The operas of Monteverdi are much closer to home than through-composed more recents; there’s dancing too, and more sex on stage than killing. The suites or partitas of Bach share important features with the vinyl albums of recent years — two to a disc, sets of about six two-to-three minute pieces written to dance rhythms, even if they’re not quite dance-able. They are varied and short with many new beginnings. They survive short attention spans.

The acoustic classical orchestra can be fertilized rather than wrecked by the introduction of electric instruments, especially the guitar.

As to procedure: if there is one thing I’d love to see rescued and passed on, it’s formal counter-point.

What we need are really strong composers, who live in the cultural dog’s breakfast of the present day and want to appeal to everyone.

Shostakovich proved with Op 87 that the human brain remains capable of this, or some brains do. These must be found early and motivated, before they attach to investment banking or airfoil design.

I have my own ideas — pretty damn good ones, I must say — on how to shake the current situation up but alas no one is asking me, even though I often walk by Carnegie Hall.

Maybe one day I’ll let em know anyway!

I stopped reading, for obvious reasons, at:

“The acoustic classical orchestra can be fertilized rather than wrecked by the introduction of electric instruments, especially the guitar.”

But I have a remark on something in the passages before that disastrous deraillement.

A sonata structure does not have to be rationally ‘followed’ to become meaningful in the listening experience. It is a procedure to give meaning and momentum to a piece and it is then being experienced subliminally by players and audiences, one can feel the logic of the form. Anyway, any structure is only a means to keep the interest going, as Ravel claimed, quite a sobering thought and entirely true. I’m sure even Beethoven would not have given a damn about whether audiences would get his formal sophistication or not – he would be concerned about the emotional effect of his structures, that is where they are for. And so it is with every truly great music. Who, in any audience, understands the structure of Debussy’s Prélude à l’Après-mini d’un Faune? Not even the players have any clue. They all just experience the unity and logic of the music and that is enough. Structure is only important for the composer, to get his expressive effects.

Heart of my sonata-form point is that shorter forms are more appropriate for today, not to supplant everything else but to allow more music into more places and for more listeners: a way in.

As to my electric suggestion: you might take note that the symphony orchestra stopped evolving, adding new sounds, more than a century ago. I grew up listening to Segovia but the guitar has flopped as concerto instrument and compared to the electric evolution, has become a bore. The lute is something else, but so quiet . . .

You have a lot to teach on some subjects but your overbearing tone makes it hard to listen — for me anyway — along with a tin ear for other opinions and a tendency to errors of fact.

Concerning facts:

‘New sounds’ have been, and are, invented all the time by composers using the same collection of instruments. It is a very important fact that the symphony orchestra is such a malleable instrument, that an inventive imagination can create sounds that are very individual and entirely ‘unheard of’. Think of the different sounds of all the great composers since Haydn. When you hear Stravinksy or Debussy, they are worlds apart, and yet use the same instruments. Attempts to extend the range of actual instruments with saxophones, ondes martinot, etc. did not catch-on and the literal inclusions of extra-symphonic sounds like anvils (Wagner) or cow bells (Mahler, Strauss) remained an exception, for a particular and specific occasion. Electric guitars don’t fit into the mix, and are not necessary at all, except when a piece is supposed to invoke pop music in a most literal way – which never ends well. Even sonic art works can make use of the normal orchestral instruments, imitating electronic sounds, or eerily unearthly patters like Morton Feldman.

These misunderstandings, driven by the wish to ‘develop’ the orchestra as if it has become ‘old’, are comparable with the wish to ‘further develop’ instruments like the violin. When the evolution of an instrument or an ensemble type stops, that does not necesserily mean that it has become stuck, but that a range of possibilities has been reached which does not need further evolution. So it is with the symphony orchestra. It is finished because its riches have shown to be more than enough, and new sounds can easily be invented by a composer with enough interest in sound or with enough invention.

And then, ‘new sounds’ are irrelevant to the quality of the music being written for the orchestra.

PS:

And as for the tone: my longer comments are dictated and my PA says she wants to make sure that the tone will irritate a certain type of reader.

Pierre Boulez was a sacred cow among. No matter how cold and lifeless recordings the critics would praise him. I once said that Boulez could fart in perfect rhythm in concert and the critics would say it smelled sweeter than honeysuckle.

PB conducted the notes of a score but not what is between or behind the notes (Mahler: ‘music is what is behind the notes’; Debussy: ‘music is in the silence between the notes’). He tried to render the score as clear as possible, without pathos. It was a materialist approach – music as sound.

I agree that not all of his music is easy to listen to, but I think his Notations (both in the original piano & orchestral version) are a masterpiece of the 20th century.

I’m also a huge admirer of his conducting of the orchestral repertoire by Debussy, Ravel, Bartók, Stravinsky & the Second Viennese School. Yes, his interpretations (especially of Mahler) can sometimes feel forensic & cold-hearted but I always hear something fresh in his interpretations – new colours or textures, small yet significant details which can get lost easily in performances under other conductors.

I passionately love the man, dream about him & feel liberated form all of my anxiety listening to his music. All that muddling with the soul & stuff of all those old fogeys! it’s senile to never want to grow-up & we should fully embrace the NOW of modern times. Pierre discovered & defined once and for all what modernity is, let’s be grateful instead of all that complaining. I feel already the need to listen to a Pli again!

Sally

Haha! I love it when you slip into Satire-Sally!

Boulez co-founded the Lucerne Festival Academy in 2003 1100 students/professionals from 60 countries have participated. He also led Conducting Masterclasses during the Festival. Apart from his conducting the BBC and New York Philharmonic he also conducted the Lucerne Festival Orchestra in New York when Abbado was indisposed. One of his last Concerts he conducted a Mozart Piano Concerto with Ushida as soloist

He meant a lot to me. I loved working with him and around him at Lucerne Festival; he was the real deal.

I never saw Boulez conduct, and I’m not a great fan of his music. At the same time, his recording of Bartok’s Concerto for Orchestra is outstanding.

True, D**.

In fact, all of Boulez’ Bartok recordings are outstanding, particularly his earlier ones, the ones on Sony Classics.

And his big Ravel set (also on Sony) contains some of the finest performances of that music ever recorded, and is superior to his DG recordings.

I tend to agree. What particularly amazes me is that he achieved these results without a baton.

Boulez is (also) a destroyer.

“History will say—history says now—that the 12-tone movement was ultimately a dead end, and that the long modernist movement that followed it was a failure.”

“Deeply flawed at their musical and philosophical roots, unloving and oblivious to human limits and human needs, these movements left us with far too many works that are at best unloved, at worst detested. They led modern classical music to crisis, confusion, and, in many quarters, despair, to a sense that we’ve wasted decades.”

Source: http://www.davidvanalstyne.com/pg-problematonalmusic.html

There are some problems with that well-meaning article.

The inner resonance with the emotional inner life that listeners experience, is not an illusion, as the article maintains, it is not a projection, it is a real property of the music itself. It has been meant as such by the composer.

Dissonance as tension is only one property. A dissonance as an unpleasant sound is not a ‘thing’, it depends upon context. What is a dissonant effect in one work, may be a consonant effect in another. Also, dissonance can be a colouring of the music, not needing resolution at all, as in much of Debussy or Ravel or Szymanowski or Stravinsky. It is a gliding scale meaning different things in different types of works and styles.

That Schoenberg simply rejected consonance and happily embraced dissonance is a simplistic reading of history. Schoenberg felt that the musical style of his time, in the Austrian-German musical tradition, was getting terribly banal by over-use, and he sought a way of refreshing the musical language by using combinations that had not as yet been tried-out and that was indeed the much more dissonant territory. His very dissonant music of before his 12-tone idea is still music, expressing negative emotional states, in accordance with expressionist aesthetics: attempting to express the awful, the horror, the destructive and nihilistic sides of life experience. But the article is correct in stating that the proposal that this were progress, was utterly wrong.

Well yes. But you give Schoenberg’s early works far too much credit, in my opinion.

He was not able to control what he intended the listener to experience.

He was just constructing stuff, that yields a response by the listener, but not one that was ever intended, but one is a byproduct of his construction.

Today incredibly many composers are mere constructors, and within the modernist real a dare say almost all.

I agree with the last sentence.

But not with the remark on early Schoenberg.

No single piece has ever better expressed the deep desolation that some people can sometimes experience, than Schoenberg’s ‘Vergangenes’ from the Five Orchestral Pieces:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dwnBAtpqOJw

I dispute that the effect is intentional.

It is simply a byproduct of his construction.

If you’re looking for evidence for this view, consider:

“The titles of the pieces, reluctantly added by the composer after the work’s completion upon the request of his publisher”

Schoenberg about op.16, 3rd movement:

“The conductor need not try to polish sounds which seem unbalanced, but watch that every instrumentalist plays accurately the prescribed dynamic, according to the nature of his instrument. There are no motives in this piece which have to be brought to the fore.”

Murray Dineen: “From the perspective of a fundamentally flawed work, I am forced as an analyst to go beyond the score in admitting evidence. Above all, I am forced to invent evidence (something analysts are not accustomed to doing) – my notion of various musical spaces stemming from the opening contrapuntal combination. Had I been able to adopt a premise of organic unity in “Vergangenes,” I could limit my analysis to within the bounds of the work and avoid straying into ancillary questions. But by invoking the notion of a “flaw” I am forced to seek external support for my conclusions about the work’s failure. A flaw, after all, is not the product of a work’s inner nature but rather produced by some lack or excess in which the making of the work, its design, and the ability of its own terms, intrinsically. A flawed work fails only with regard to some standard above and beyond itself, to which, for reasons likewise extrinsic, it does not measure up. “

Yes, I know Schoenberg’s utterances concerning the Five Orch Pieces.

But if you read about how he described his own music, his methods, his relations with players, critics, audiences, then you realize how defensive he always was and wrapped-up in the problems of getting his theoretical intentions across. So, his ‘reluctantly given titles’ of op. 16 are not to be taken very seriously, he wanted to be seen as an objective, theoretical, progressive composer and not as a dying romantic, which was the truth – and he knew it. He felt his romanticism was backward, and he wanted to be avantgarde and at the time that was: rationalistic (Vienna being also the hotbed of the new rationalism in philosophy: Wittenstein).

His lack of practical insight in performance shows in his comments about nr 3 of the collection, which consists of chords in ever changing instrumentation. Given the nature of the instruments, his instructions are not helpful at all, and a conductor can only bring-about an impression of the score by carefully balancing the dynamics. The only thing a conductor can do, is avoiding giving prominence to details, but that is already involving careful balancing.

The quote by Dineen is gobbeldigock – someone not understanding ‘Vergangenes’ and trying to find a way around it.

I really think Schoenberg expressed in ‘Vergangenes’ a profound moment of life experience, and felt ashamed about it for its open emotionality, and therefore tried to cover it up, like someone caught under the shower and protecting his sensitive areas.

Also his other expressionistic works are hyper-romantic, with Pierrot Lunaire and Erwartung as highlights. In Schoenberg’s psychological problems the entire 20th century’s psycho problems are clearly exposed. Understanding Schoenberg = understanding 20C modernism.

This week it’s also the 4th anniversary of the death of Georges Pretre who didn’t have the notoriety he deserves in his country and the other very big french conductor of the last 60 years. And he was completly the oposite of Boulez in front of the orchestra.

Who talks of Boulez nowadays? … Norman Lebrecht! Next question … and a bit more difficult too, please!

Well, what about this one:

Why are so many of orchestral staff stubbornly oblivious of the revival movement in music as represented by David Matthews, Nicolas Bacri, Karol Beffa, Pierre Jalbert, Jake Heggie, Guillaume Connesson, Paul Moravec, Aaron Jay Kernis, Jonathan Leshnoff, John Kinsella? Why is an important book like Robert Reilly’s ‘Surprised by Beauty’ entirely ignored by such people? Why are they only concerned about bums on the seats – without realizing that these bums will happily buy tickets if informed about this movement and the surprises it represents?

I heard Connesson’s ‘Flammenschrift’ from Stockholm the other day – a remarkable gift.

Voilà.

Boulez in a nutshell: the anti-Brahms.

That’s a good one.

It’s unfair to blame Boulez too much for the effects of the modernists, Darmstadt school etc on modern music. There were many willing accomplices, not least academics for whom taking up the latest trends gets them the kudos they seek.

But Boulez was a wrecker, from deliberately disrupting concerts of composers he despised ( in his early days) to his later complete dismissals of those who did not share his aesthetics. Real harm was done to admirable composers.

I remember watching TV programmes in which Boulez performed and explained his music. He took great delight in explaining the way his music was constructed and the how ‘patterns’ moved around the orchestra – but on listening the effects were just ordinary. The processes may have looked good on the score and their complexity would doubtless have given Boulez much pleasure. I was reminded of Hans Keller’s descriptions of composers constructing ideas whose complexity was ‘inaudible’.

And yet …I have a radio recording of Boulez conducting Martinu ( a composer very far from Boulez’s aesthetics). In Martinu’s 1st Cello concerto, Boulez provides a most wonderful orchestral accompaniment to Pierre Fournier.

Boulez occasionally surprised me in his recordings.

I came to expect the excellence of his Bartok and French music, and was not disappointed.

I figured his Beethoven and Mahler might be sub-par, and they were.

But he did a GREAT Royal Fireworks Music and Water Music Suite for SONY, with the NY Phil.

Amazing!

I saw Boulez conduct in Cleveland many times from the 1970s to his last appearance (Mahler 10, Wunderhorn songs). The concerts were unforgettable. Early on, he took the audience through a “tour” of the Rite of Spring, explaining how the piece worked, then conducted Part 2 along with Symphonies of Wind Instruments. There was also an astoundingly beautiful Daphnis & Chloe Suite 2 with choir.

Great composers create music from the head and the heart. Because Pierre was so brilliant his music tended to come more from the head. His emotional life was very reserved and it showed up in his music. As a conductor he always made sure that the musicians played what was written in the score. He did a Mahler 9 with the New York Philharmonic in Carnegie Hall that was utter perfection. He was a good, decent person, but no one is perfect so we poor mortals can always find him at fault.

Bravo, Stephen. Those of us whose first encounters with him were SO far back at Harvard remember him well and warmly!

Karma, I was the first person to greet him when he came to Harvard in the spring of 1963. It was love at first sight. When he came to NY he needed a family so Roberta and I were just that. His tuxedo tells you everything you need to know about his conducting. It was strictly formal on the outside and crimson on the inside. He never forced the passion on the music. He allowed the composer’s intentions do that for the audience. As for his compositions, let’s see what audiences think fifty years from now.

What a silly comment.

PB did his very best to promote a damaging music philosophy, which was sheer totalitarian propaganda of an antimusical ideology – because he lacked a great deal of musicality himself. Proof? Read his writings, check his musico-political actions and utterances. Even in old age he continued to believe in the ‘modernist revolution’, as his involvement in the Ducros affair shows.

“In 2012 a lecture at the Collège de France by the pianist Jerome Ducros criticising atonal modernism, drew a flood of furious, hateful condemnations from the modernist establishment. The ‘affaire Ducros’ created a flow of articles pro and contra that ran in the media until 2015.”

https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/J%C3%A9r%C3%B4me_Ducros

https://slippedisc.com/2017/05/is-france-rejecting-the-boulez-line-for-the-bacri-solution/

People should not be distracted by the friendliness of outward appearances, we know the thinness of such behavior since Hitler and Stalin who were really friendly with children, young women, and dogs.

As one of those crude people who have no time for the ivory tower of atonalism, I’m not a fan of the music of Boulez. I’ll leave that to those who are more intellectually gifted than me. It seems that all composers suffer a period of neglect after their deaths and he may return victorious in a generation or two. However, I would be very sorry not to have his recordings of Bartok, Ravel and Stravinsky. Of course I only have the DG recordings but I’m more than happy with them.

Oh come on! Start trusting yourself a bit, man.

Atonal rubbish is just that: garbage.

Your ears, your perception and most importantly the way the music resonates with you is spot-on perfect.

It has nothing to do with intellectual. Music is there for the souls of humans. True music – that is!

Of course there is stuff for the intellectually pretentious, snobbish pricks as well. Boulez and many others fit that bill well enough

“I would be very sorry not to have his recordings of Bartok, Ravel and Stravinsky. Of course I only have the DG recordings but I’m more than happy with them.”

Barbarian, it’s pretty easy to hunt up Boulez’ Sony recordings. Sony has reissued all of them in various permutations – just go to Amazon and you’ll see what I mean.

But don’t get me wrong; those DG recordings are quite good (with the exception of Boulez’ perfectly played but soulless Mahler, PB’s DGs are better than most of their rivals); but the Sonys are just *that much* better.

Good luck in the shopping arena!

His DG recording of Daphnis & Chloe is almost obscene in its sensuousness. Ditto the Scriabin Piano Concerto. His recordings of Petrushka and Sacre are legendary.

Boulez was a man of contrasts. He was possessed of an enormous degree of intellectual ability but seemed to antagonise people wherever he went.

The famous joke from BBCSO days was:

Q. If you simultaneously drop Boulez and Gielen from a 100ft tower, which one hits the ground first?

A. It doesn’t matter.

Sorry about the bad taste but that’s the sort of reaction he caused as a person. As to his music well, what can one say? He understood what he was doing and what it should sound like but does that mean that any apart from a select few would want to listen to it? His mind worked like an advanced computer but to many, from ordinary concert goers to the top pro players his music sounded like someone had fallen over in a percussion store room and pushed a piano over the edge of a stage.

I don’t expect to be able to sightread everything, particularly new pieces, but equally I don’t expect to have to have to sit trying to work out note placements and rests with a calculator. I think time hasn’t been very kind to his memory so far and I have a distinct feeling that as the years progress his work will seem like yet another 20th century blind alley. Time will tell.

In music life, and especially in the circles of contemporary music, true intellectual activity that deserves the name is usually only to be found in academia: musicology. But musicology often suffers from lack of musical experience in the heat of the practical field. Musicians are not intellectuals but their intelligence locates in the emotional field, it is emotional intelligence. The more musicians are talented, the more emotional intelligence – that is, for music, they may still beat-up their partner. The same with composers – that is, up till the Schoenbergian type of composer who puts his intelligence in front of invention. (Debussy, one of the most brilliant and most intelligent composers ever, was entirely aware of the role of the intellect in composition.) PB was very intelligent, and in music life he thus formed an exception, hence his influence; but musically he was very restricted in terms of talent. He made the most of his gifts, which meant: separating the rational from any musical consideration, which suited him best. In doing so, he merely reflected a much broader trend in the last century, to approach everything in life rationally. In the arts, that leads to devastating poverty.

Boulez famously didn’t leave a will and his siblings had to pay staggering death duties. If he’d got lawyered up, he could surely have got some of that money going to good causes – his Lucerne Academy for example. Or music teaching in schools. I think he thought the world would die with him

Pierre Boulez, the only conductor who could make Janacek sound dull……….and that takes some doing!

He put a lot of effort into that interpretation, suppressing the energy which threatened to pop out all the time.

Many of the work he conduct never had a CD release ! I think it is necessary for DG to do this