What Liszt and Schumann got from Beethoven

mainWelcome to the 115th work in the Slipped Disc/Idagio Beethoven Edition

Franz Liszt/Ludwig van Beethoven: Fantasia for Piano and Orchestra on motifs from Beethoven’s ‘The Ruins of Athens’

We have seen what Liszt did for Beethoven. We know, too, of Liszt’s role as a catalyst between the age of Beethoven and that of Richard Wagner. Liszt, who became Wagner’s most loyal supporter and eventually his father-in-law, often played Beethoven sonatas for Wagner, on one occasion, reducing him to tears in the slow movement of the Hammerklavier sonata.

Liszt carried much of Beethoven’s in his head, borrowing a theme here or there in his own scores. The most famous of his borrowings is the incidental music that Beethoven wrote for an 1811 play, The Ruins of Athens. Liszt decided that what Beethoven’s orchestral score needed was a prominent part. The result is a cataclysmic horror show, the sort of thing a stand-up comic like Dudley Moore would write as a parody of Beethoven or Liszt, or both of them together.

Liszt published his tribute in three versions – for solo piano, two pianos and piano and orchestra – all of them dedicated to the Russian pianist and composer Nikolai Rubinstein, who was his arch-rival at the time. In the version with orchestra, Liszt keeps the piano under wraps for a long stretch, before blowing in the soloist with a storm, soon followed by Beethoven’s Dervish Chorus and his overworked Turkish March. It’s fun and frisky and possibly self-mocking.

There are several recorded versions of varying degrees of seriousness, the earliest of which dates from September 1938 with the pianist Egon Petri and the London Philharmonic Orchestra, conducted by Leslie Heward, who was music director of the City of Birmingham Orchestra. It’s a buttoned-up strait-laced performance and all the better for that. Petri was an emigre Dutchman with Liszt-like hands who was much in demand for the most difficult and prestidigitatious works. His playing of this piece is practically unsurpassed.

A Russian recording by the USSR State Radio and TV Symphony Orchestra conducted by Alexander Gauk is interesting for the opportunity it afford to hear the pianist Grigory Ginzburg (1904-61), a Liszt specialist who was hardly ever allowed let out to perform abroad. It may be my fantasy, but I find an authenticity in his approach which stretches back to Rubinstein and Liszt himself. The sound is Soviet bog-standard, barely listenable in parts.

Of the remaining recordings, Kurt Masur has outstanding orchestral sound with the Gewandhausorchester Leipzig in 1991 and Michel Béroff as soloist, but takes the whole thing too seriously.

One other Liszt tribute to Beethoven we need to consider is his

Inauguration cantata for the Beethoven Monument in Bonn

The words warn you to expect a sententious, sancimonous exhortation at an occasion attended by the crowned heads of Europe, and the music lives down in every section to our lowest expectation:

Holy! Holy! Holy

is the genius’s sway on earth.

He lent us a foretaste of heaven,

immortality’s surest pledge.

This celebration has united us!

Set foot within the circle;

let us devote these varied hours

to his memory...

There are moments – the start of the third movement, for instance – when Liszt displays his mastery of orchestral invention but barely has he drawn us into a theme that he sets a soloist loose on a tangent that has nothing to do with the musical context.The finale, marked ‘andante religioso’, smells of incense and baked beans.

There appears only ever to have been one recording: by Bruno Weil in 2020 with the Cappella Coloniensis, Kölner Kantorei and soloists Diana Damrau, Jörg Dürmüller and Georg Zeppenfeld. Listen to it here. Don’t say you haven’t been warned.

On a more reasonable note, Liszt’s transcription for piano solo of Beethoven’s love song ‘Adelaide’ is pure pleasure. Egon Petri gives a reminder that muscular pianists can also be microsurgeons, while Garrick Ohlsson in far superior sound suggests at hidden affinities between Beethoven, Liszt and Schubert. It’s ten minutes well wasted.

Robert Schumann: Studies in the Form of Free Variations on a Theme of Beethoven

In 1830, the profoundly insecure 20 year-old Schumann was writing piano studies on Beethoven themes that would never be played or published in his lifetime. This singular set is built around the second movement of the 7th symphony and is riveting for the way we hear Schumann learning point by point from the master which angles to use in developing a theme. At around eleven minutes you will hear an echo of the opening of the 9th symphony and wonder what it’s doing there.

The Etudes are rarely progarammed in recital halls. The most compelling available performance on record is by the London-based Hungarian pianist Peter Frankl, a scintillating retracing of Schumann’s rising excitement as he discovers the means that Beethoven puts at the disposal of future composers. I have never heard this set performed live and it’s now near the top of my wish-list. Frankl, who is 85 next month, still gives an occasional recital.

Other interpretations can be heard from the Frenchmen Simon Ghraichy (2019) and Eric Le Sage (2010), both distinctly different.

I think you’re moving too far afield of the subject in your Beethoven project, Norman.

Of course Liszt and Schumann both considered Beethoven a “God” of music. Duh! Their musics, throughout both of their careers, reflect numerous influences of Beethoven.

Liszt in particular was a Beethoven “worshipper”; he was the first to play all of Beethoven’s 32 piano sonatas in public. (In fact, Liszt essentially invented the modern piano recital.)

But if you’re planning to start putting up variation sets or studies or works “in tribute to….” Beethoven in your vaunted survey, then stop. Just stop.

Otherwise we’ll all be here until we expire from ennui.

It was equally Clara Wieck who invented the modern recital with her programs where the works were played more or less in chronological order and without embellishments. And without showwomanship and audience hysteria.

Interesting works and marginalia. Liszt’s cantata includes an orchestration of the Archduke Trio religioso adagio, with chorus as I recall. but nearly provoked a riot of protest by starting the premiere over when the royals arrived. I remember Egon Petri’s “Ruins of Athens” fantasia with Leslie Heward as being with the Halle Orchestra, but Norman says LPO and is probably right. Liszt has as much fun with the ‘Turkish March” as Josef Hofmann did later.

Petri was a highly regarded Busoni student and champion, nominally Dutch but of German descent, but somewhat clunkily recorded on Columbia laminates. His Schubert-Liszt “Lindenbaum” is a graeful exceprion

Petri taught for many years at Mills College, Oakland, with Darius Milhaud and Bernhard Abramowitsch on the faculty, and played the Beethoven sonata cycle in the late 2950s in Veterans Auditorium in San Francisco that I attended. It was recorded by local sound engineer Richard Wahlberg and issued on Westminster LPs. He recorded Chopin-s preludes for Columbia to compete with Cortot’s, and Liszt’s Petrarch Sonnet 104 that rivals Horowitz’s and Kapell’s, also a Tchaikovsky first concerto that doesn’t.

“…………….and played the Beethoven sonata cycle in the late 2950s in Veterans Auditorium in San Francisco that I attended.” A striking foresight! and a hopeful signal that Beethoven pieces will still be around in 930 years.

In a sense Liszt’s B minor sonata of 30 mins is essentially Beethoven’s Hammerklavier sonata of 43mins, boiled down to its dried residue. op. 111 has two contrasting movements, the second being an Arietta with variations.

As Brendel points out in his book Veil of Order, it is a prelude to silence. Had Beethoven lived longer it is possible he might have composed a one movement sonata. I seem to recall reading somewhere Beethoven saying that piano music in the future must involve the poetic element, making a fugue is not really art. Both Liszt and Schumann seem to have followed this path, the latter more than the former.

If writing a 3 movement sonata, followed by a 2 mvt sonata, and then 1 mvt sonata (Alban Berg) is a developing trajectory, then the end point is Cage’s 4’3″.

Sorry about the typo, the piece is 3″ longer than that.

I disagree. Silence is not music. Though I would prefer it to music composed post 1900.

Beethoven’s sonata op 101 is a harbinger of Schumann. His Fantasie in C quotes from An die ferne Geliebte

Why not a one-movement Beethoven sonata, though it would confound his duality of tension and relaxation? Domenico Scarlatti wrote hundreds of them, but that’s not quite the same. There is a one-part Invention by Cage that stretched his limits and was also a prelude to silence.

It could be based on a five note motif, B-E-E-H-E using the pentatonic scale!

For JC, silence was the best of his inventions.

Yes, John, writing one-movement sonatas will probably never be a growth industry. As you know, the surest way to ensure a response here, and often the only way, is to include mistakes. I haveonly the excuse of haste, sloth, andlegal blindness, which is no excuse at all.

Garech De Brun in his nomdeplumage cites Beethoven’s Sonata 28 in A Op. 101, once known as “the little Hammerklavier” due to a publisher’s use of German musical terms over Italian at Beethoven’s behest. In 15 minutes it manages four movements, a club-footed Alla Marcia, and a fugato mit Umkehrung. Even Gieseking sounds awkward in it, and no less than Horowitz called it difficult when he performed and recorded it in late career.

An Australian musician says Umkehrungen (Inversions) are the only things that sound right to him, standing on his head down under, poor fellow.

I’m trying to fix Schumann’s quotation of “An die ferne Geliebte” in his Op. 15 Fantasy. There is a moonlit spot that Benno Moiseiwitsch brings out beautifully, Richter a bit less so..

I think opus 101 is a marvellous masterpiece, and the Alla Marcia does not suffer from any physical handicap – maybe it sounds clubfooted when played by pianists who don’t understand the music. It is a very uplifting movement, contrasting with the romantic opening mvt, and with some extraordinary dissonances, rather unusual with Beethoven. The whole work is full of inventive ideas and wild developments, full of surprises and brilliantly worked-out – for instance, the transition to the finale.

Music grows out of silence and returns into it. How beautiful are these returns, and these silences, that set it apart, mark its limits, frame it like a painting, and increase its value by rarity, so that demand exceeds supply. Sometimes it seems that it is we who have stopped, while the music goes on.

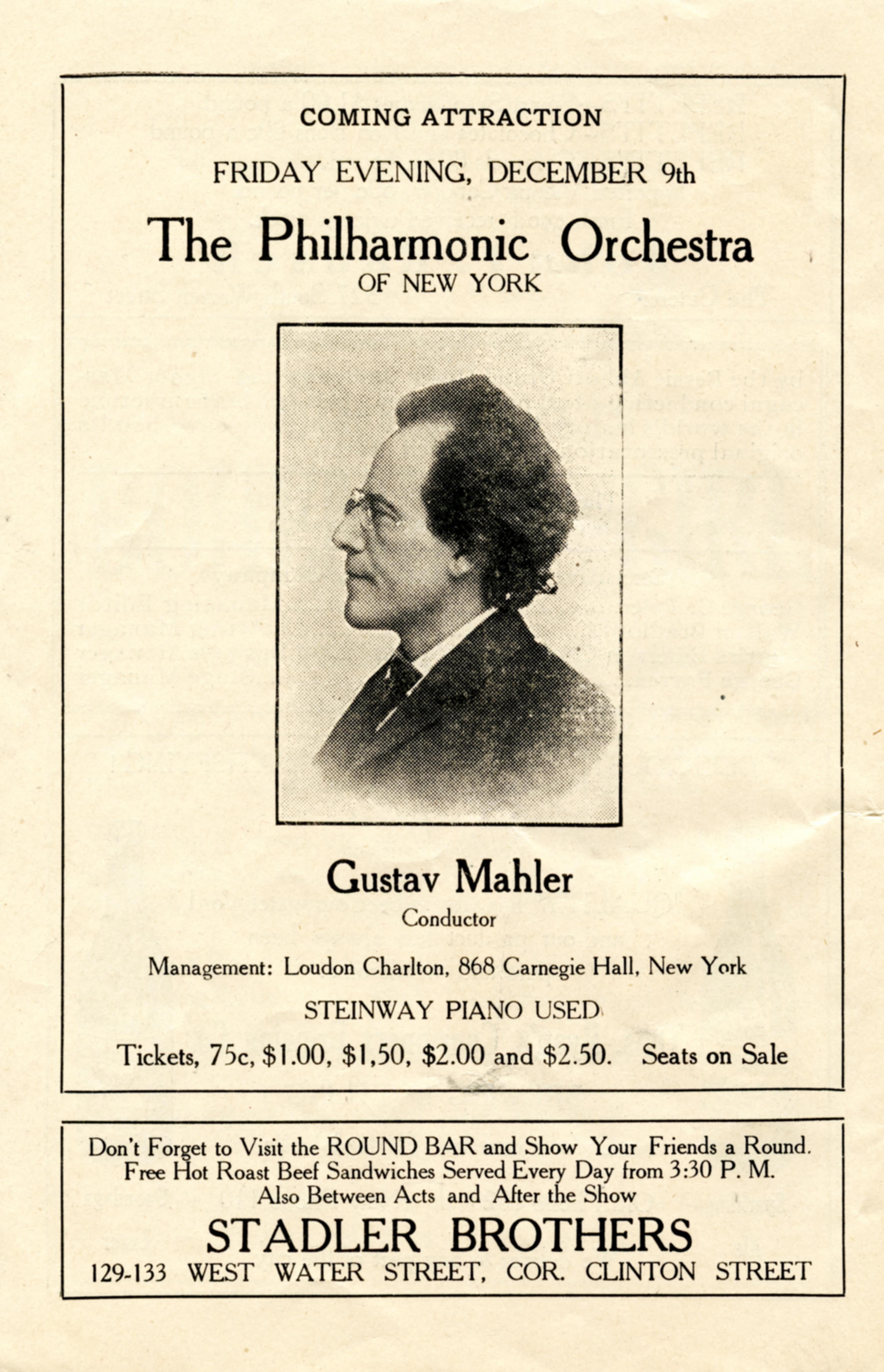

Music has rests, like divine labours. Schnabel conceded others might play the notes better, but that he excelled in the silences between the notes. Mahler incorporated silence into his score for the “Resurrection”, asking for five minutes of it before the Urlicht, “O Roesschen rot” emerges rom it.