The ultimate conversation of violin and piano. The ultimate interpretation?

The ultimate conversation of violin and piano. The ultimate interpretation?

Our new partners at operaplus.cz have come up with a lost recording of Vaclav Talich conducting Smetana’s Libuse, just before the Nazis banned Czech operas.

Thrilling stuff.

Listen here.

Friends have reported the death inPhiladelphia of Mouhamed Cisse, a gifted cello student. Mouhamed, 18, was shot last Sunday during the protests, but not as part of them.

A member of Musicopia String Orchestra, he attended the Philadelphia School District Instrumental Music Program.

Ceci Cipullo writes: ‘My friend Mouhamed Cisse, who I’ve been growing up with at summer camp with for six years, was shot and killed in his home town a Philly. Amidst all this chaos and protests, another innocent black man has lost his life. Mouhamed was 18. While it is not known yet who did it, he is still a victim of gun violence. He was hysterically funny, so kind and talented on the cello. I’m asking that you please donate what you can to his memorial fund, and also to other Black Lives Matter causes so senseless killings such as this one will never happen again. The money will go towards his family.’

Almost $50,000 has been raised here.

Camp Encore/Coda writes: ‘We are so very sad to say goodbye to Mouhamed Cisse, who was killed Sunday night near his home in Philadelphia. Mouhamed was an important part of our camp family for many years and will be sorely missed by all of us who knew and loved him. Our hearts go out to everyone in his family and our camp community in the wake of this terrible news. We will be announcing a memorial event once we have put our plans together.’

UPDATE: Mouhamed’s former counselor Daniel Hopkins tells Slipped Disc: ‘Mouhamad’s killing was not related to the protests in Philadelphia. Misinformation about his death has been spread on social media, because it occurred on the same night as protests. He was shot near his home.’

UPDATE: The Philadelphia Inquirer has finally reported Mouhamad’s killing, adding that no arrests have been made.

I’ve had an enjoyable conversation with Vasily Petrenko, outgoing chief of the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra, discussing how we re-engage with audiences once the Covid restrictions are eased and big symphonies are out of the question for the forseeable future.

Vasily is one of the most clear-sighted conductors around. He is rethinking his repertoire from one day to the next.

Watch the chat here:

Demonstators in the southwest port city today toppled the statue of the 17th century Bristolian slave-trader Edward Colston.

Belatedly, no doubt.

But Bristol’s concert hall still bears the name of its philanthropic founder.

So what’s to be done about reidentifying Colston Hall?

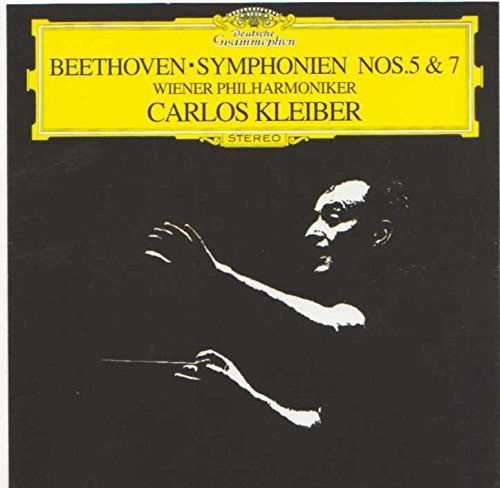

Welcome to the 81st work in the Slipped Disc/Idagio Beethoven Edition

Seventh symphony, opus 92 (part 4*)

Before we come down to the final selection, pianist Lori Kaufman in Chicago has sent us these thoughts of pressing relevance:

One of the most bitter casualties of the Great Virus of 2020, Beethoven lost out on all of his 250th birthday celebrations worldwide. We have donated the ticket costs and cancelled our travel, and all that is left is for us to play some of the late bagatelles on our piano that desperately needs a socially distanced tuning, or to scroll through an overtaxed youtube to get our fix of this titan, the man who changed sonata form forever and transformed the symphony into an expression of indefatigable human triumph. (And couldn’t we all use a little human triumph about now?) Norman tells me that the seventh symphony is up next, and we already know better than to offend our audience by claiming that one version is the “best ever,” and so I will leave it to you to decide which Beethoven 7th YOU need right now, in this bizarre time.

Does your body need sunlight and vitamin D to ramp up your immune system? Then go for Carlos Kleiber’s 1976 Vienna recording. On everyone’s top ten list, this is the version that radiates light and love and sprinkles irresistible charm at each barline. Each note of the ascending scales in the prologue is a puff of Schlag atop rows and rows of Sachertorte. As the fourth piano concerto seems to say everything there is to say about G major, this symphony is the house that holds A major, with room after room of its joy, its spirit, its hope. You won’t be able to stop yourself from whistling along with the jaunty flute when it presents the theme. If you want to obliterate the dark days of quarantine, this is the recording for you. You won’t get bogged down in the sadness of the second movement because Kleiber takes it at a cheery clip that hypnotizes you into the soothing balm of the major section. There is no time to despair, the third and fourth movement are soon there to take your cares away with their exuberance. This is the symphonic metaphor of putting on your bathing suit for the first time in summer.

Are you feeling sentimental, lamenting the “good old days?” Watch Reiner’s video with Chicago from 1954. Oh Fritz, with your toy soldier right arm, mechanically moving up and down while the REAL conducting is done with your eyes. Wait, there is Janos Starker at the front of the cello section! And Ray Still’s brilliant predecessor, Florian Mueller! It’s a pageant of the greats, with close ups in all the right places. You will have a lot of fun watching Reiner and his shocking economy of movement. He gets magisterial things out of the orchestra using only his eyebrows. Listen to the way he builds momentum in the prologue. Those ascending passages transform the humble scale into profound statements on humanity’s greatest accomplishments. Reiner’s scope is unparalleled. Watch the whole thing and you will be rewarded in the climactic end by seeing him mopping his face and then frantically trying to stuff the handkerchief back into his lapel pocket before anyone notices that he’s actually human.

Do you need an intellectual challenge? Have you already conquered the chemistry of sourdough baking, having mastered the boule, now using your starter in focaccia and even pancakes? Okay, do this: Put on George Szell and the Cleveland Orchestra and I guarantee you will hear notes that you never knew existed in this piece. Did you write your dissertation on this symphony? Szell will show you passages and lines you were not aware of. His is the only ensemble that sounds like an alien with twenty different distinct voices, all playing as one sentient being. The clarity is astounding, and never gets old. You will literally feel your brain cells multiplying.

Are you stir crazy, and would do anything to get out and go to the theatre? Watch the Hollywood version of this piece conducted by Leonard Bernstein in 1978. You will have all the drama and passion and intrigue you crave. I hope you have some microwave popcorn somewhere in the back of your pantry. Put some lip gloss on, dress up and make it into an event. After all, this is the only outing you’ve had in three months! Watch Lenny talk about Beethoven’s proclivities directly into the camera, and imagine that you will brush elbows with him at the reception later.

Are you looking for meaning to this madness? Have you already cleaned out every junk drawer in your home and organized your books according to size, shape, and the colors of roy g biv? Nobody can tame chaos like Arturo Toscanini. Whether you prefer the 1935 BBC or the 1936 NYP version (both have astounding merits), you will be blessed with order finally restored to our sorry universe. No need for a dangerous visit to the chiropractor, Toscanini will realign your limbs and sinews down to a cellular level. A master class in form, no tonic chord is played as a dominant, no dominant is without its drama, and your sanity is refreshed by every successive triumphant harmonic resolution. At certain points, Beethoven’s notes don’t even sound like they are played by instruments, but by some natural sonic emission of Nature herself. Put your trust in Toscanini to set things right.

Are you grieving? Do you need someone to sit with your sadness, someone who understands? Furtwängler does. His 1943 Berlin recording plummets to the lowest despair of humankind. You have never heard so much pain and pathos in this second movement. He takes it sloooow, and each octave rise in the strings grows even more mournful until its almost unbearable. This will accompany whatever suffering you feel. In the outer movements, the timpani goes to hell and back to save your soul. You will find what you need in this devastating recording. And then you will feel better! Do you need to hold on to some form of hope?

But what if you simply need to hold on to some form of hope? Are you feeling like your life will never be more than a treacherous five minute walk outside to the mailbox? Then consider doing something radical: Leave the old wonderful adored masters aside for 38 minutes and go on facebook and watch Het Concertgebouworkest perform their first live concert since this whole nasty business shut down music everywhere. Spanish maestro Gustavo Gimeno leads the stoic and dedicated musicians, one to a stand, 1.75 metres apart, as they play a piece that goes from joy to despair and everything in between. Allow them the dignity to get back to their life’s work, with a symphony that has a special meaning for any musician. There is no audience in the hall but you are there, proving that music cannot be shut down. Happy Birthday, Beethoven. We certainly miss you.

Lori’s recommendation of the 1943 Furtwängler concert in Berlin is endorsed by most of our experts. Costa Pilavachi writes from Athens: ‘The most urgent and exciting, Not a single note played routinely. As if lives depend on it.’ What Furtwängler achieved, as he did so often, was to convey the spirit of the moment and, at the same time, a sense that nothing in this symphony could ever be performed differently from the way they were playing it now. There is something demagogic about Furtwängler’s music making, yet also consensual. Many in the audience would carry this concert in their heads for what remained of their lives in the last two years of war.

Indisputable as Furtwängler’s account might be, the interpretations of his antipode Arturo Toscanini possess even greater power and authority. Leonard Slatkin is gripped by the Maestro’s 1935 concert with the BBC Symphony Orchestra: ‘It grabs me in a way that no other performance does. The balances are amazing, even with the limited technology of the time. Edge of your seat listening at its best.’ In my listening, the Allegretto in particular conveys vast human compassion without a trace of the German conductor’s self-pity. Somewhere between these two peaks lies an eternal truth. And not just between these two.

Erich Kleiber‘s austere 1950 performance in the Amsterdam Concertgebouw was long held to be the benchmark interpretation – poised on a knife-edge of human destiny. ‘ His sense of proportion and ability to elicit differentiated gestures for every motif is, to me incomparable; on top of which, his elegance, exuberance and own sense of wonder at the music is so intense and moving,’ comments the Danish conductor and violinist Nikolaj Znaider. Austerity governs the finale: this is no invitation to the dance.

Quarter of a century later, Carlos Kleiber slew his father Erich with a performance so calisthenic it makes listeners leap from their seats and whirl round the room with whoever is available. Carlos Kleiber’s account of the Seventh with the Vienna Philharmonic was issued together with his interpretation of the Fifth, which many critics regard as definitive (an awkward designation for so fluid an art as orchestral music) and which grips us all with a sense of wonder. This Deutsche Grammophon production might well qualify as the most important classical release of all time. The Seventh, on the seventh hearing, acquires an aura of ne plus ultra.

Except that my Spanish colleague Juan Lucas, editor of Scherzo magazine, believes the May 1982 Carlos Kleiber concert in Munich is even more overwhelming. Try it.

This debate may never end.

* Previous parts of this discussion can be read here.

I share some thoughts on The Critic website about the unintentionally hilarious Channel 4 pseudo-thriller ‘Philharmonia’:

…. I spot the perpetrator with two episodes to go and the rest dwindles out like the last half-hour of Pierre Boulez’s Répons 3, one work of many in which a composer lost his spark.

Disappointed? I was devastated. The lives of orchestral musicians are packed with enough raw drama and humdrum repetition to make a credible story. Like the concertmaster who had jus primae noctis with every female violinist, or the oboist who took a cut of new sponsorship to keep both wife and mistress in style, or the play-away manager who came home from tour to find his clothes strewn all the way down the street. Everyday stuff that makes EastEnders look tame….

Read on here.

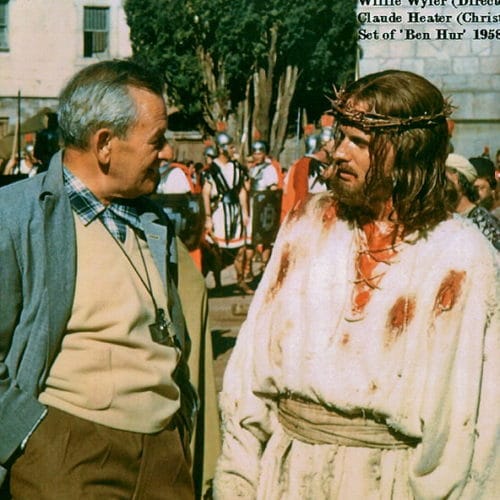

Claude Heater made his first splash in the 1952 world premiere of Leonard Bernstein’s Trouble in Tahiti. He sang three years as a baritone at the Vienna State Opera and eight at San Francisco before pushing his voice up to Heldentenor range and making a Wagnerian career.

His greatest role, however, went uncredited. He performed as a body double for Jesus Christ in the blockbuster movie Ben Hur. His face was unseen and his voice unheard, but his hands were just right.

Claude Heater died in San Francisco on May 28 after a long illness. He was 92.

More here.

This was the scene after Daniel Barenboim’s Musikverein concert for an audience of 100, including Anna Netrebko.

Worth it?

Risk assessment: Man of 77 travels from one country to another to perform music for 100 privileged people.

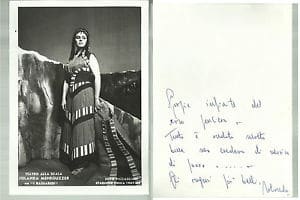

The Belgian site Opera Nostalgia reports the death of Jolanda Meneguzzer, a Florentine soprano who enjoyed a good international career, after making her Met debut in November 1963.

She categorised her voice as ‘lirico-leggero’ and steered clear of frontline stardom, but she managed both Musetta and Mimi in La Boheme and was never out of work in a long career.

She sang in the 1968 La Scala premiere of Henze’s Bassarides.

I am distraught at the death of Allan Evans, prolific pianophile, record producer and friend, a man who could bring wit and life to the dustiest corner of keyboard history. Allan was 64. I do not yet know the cause of death.

A man of exotic family background, Allan released more than 200 lost or forgotten recordings on his exquisite Arbiter label, among them Busoni and Schnabel with their students, Mahler’s associate Oskar Fried and the Cairo piano master Ignace Tiegerman. The sleeve notes alone are collectors’ pieces.

Allan wrote biographies of Ignaz Friedman and Moriz Rsenthal, and taught at Mannes College.

I never spent a dull moment with him.

Tim Page writes: Allan Evans, wonderful friend, scholar, biographer, record producer, family man, aesthetic philosopher, delighted conversationalist, truth seeker, lover of good food and wine, passionate influencer and so much more, has died.

I’m grateful to have known him from his teens, when we discussed old piano records at the counter of the Skyline Restaurant and our eyes would brighten. Thanks for all the kindnesses and good lessons, my friend. There is a void in a lot of worlds tonight — but you’ve left us so much.

My condolences to Beatrice and Stefan. May his memory be blessed.

Welcome to the 80th work in the Slipped Disc/Idagio Beethoven Edition

Seventh symphony, opus 92 (part 3 – previous 2 parts here and here)

Our expert panel in a dozen different countries has come up with remarkable unanimity in their choice of the three quintessential recordings of this symphony. All seem to agree that one performance is indispensable and two others are so anthithetical that they can’t both be right. We’ll come to these disputations in a few paragraphs’ time, but meanwhile there are more than 100 others to consider and some will open your ears to a different and unexpected approach to Beethoven’s truth.

Arthur Kapitainis in Montreal, for instance, swears by Leopold Stokowski’s fabulous Philadelphians in 1927. This recording is not yet on Idagio, but some discreet hand has uploaded it onto Youtube, where it has received a mere handful of clicks and just one response. At the end, there is a spoken commentary by the conductor. His English accent is a bit like Antonio Pappano’s.

Arthur says: ‘Every bar alive in the first movement. The Allegretto is made an Adagio, in phrasing if not tempo, but it is mesmerizing. Fine madness in the finale.’

Luis Sunen writes from La Coruna, Spain: ‘The one that I prefer is that of Pablo Casals in Marlboro in 1969. Some minor imperfections but pure vitality, pure joy with a conductor who was then 92 years old. And, in the orchestra, Shmuel Ashkenazi, Pina Carmirelli, Felix Galimir, Ronald Leonard, Julius Levine, Larry Crombs, Milan Turkovic… I’m sorry, but definitely: Casals.’ For the Allegretto alone, this is a must-listen.

Concertmaster Eoin Andersen in Berlin recalls indelible performances with Manfred Honeck (not recorded) and Nikolaus Harnoncourt, conducting the Chamber Orchestra of Europe in 1991. While many associate Harnoncourt with period practice, his most memorable performances are often with small orchestras on modern instruments. This particular concert, with musicians the age of his grandchildren, is particularly engrossing for its supple speeds and unexpected turns. Harnoncourt stood out among period conductors in never letting the theory overwhelm the music. This account reveals the finest qualities of his complete Beethoven cycle.

Valerio Tura in Bologna writes: ‘Vladimir Jurowski, in his mid-twenties, was invited to conduct a Summer festival concert with the ex-West Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra. It was a very hot and humid summer of 1997, the manager of the orchestra, Dieter Rexroth, kindly drove me a couple of hours north of Berlin to a very old castle in the ex-DDR Vorpommern region, amid little lakes and wetlands, named Ulrichshusen, and belonging to a wealthy family: the “Freiheer” told us that the castle had been given back to its original owners shortly after the reunification of Germany.

‘After a snack of boiled little lake shrimps with Sekt, the Sunday afternoon concert took place in what was once the wood-and-bricks barn of the castle, still a bit “délabré”: it was absolutely choc-a-bloc, packed with enthusiasts. The performance of Beethoven’s 7th Symphony I heard there is possibly not the best performance ever, of course, though it is by far the most vividly one recorded in my memory. It was Jurowski’s debut with that symphony, and with that orchestra: extraordinarily vital, youthful, well-focused, though profound, and the quality of the sound was really amazing: a rich and thick “idiomatic-German” sound. The energy of its fourth movement still gives me goosebumps.’

Memories like this remind us to check the privilege of personal experience against the possible existence of a recording. In this case, there is none. My own goosebump concert was with Klaus Tennstedt and the London Philharmonic Orchestra, some time in the late 1980s at the Royal Festival Hall, a level of intensity I had never encountered in my life. Between movements, I remember wondering if I should ever want to hear another orchestra or conductor again. The performance is unfortunately unavailable on Idagio. Listening to my own copy, I can hear Tennstedt driving the players into corridors of uncertainty where they have no clue where on earth he will lead them next. This, I thought, is how all music should be. It’s a question of trust between baton and orchestra. An earlier performance by Tennstedt with the NDR radio orchestra is nowhere near so exhilarating.

Before we cut to the chase, do not miss a pair of Idagio exclusives – the explosive Josef Krips with the Concertgebouw in 1951 and the obscure Romanian George Georgescu, whom I’m finding more and more impressive.

Several of our experts advocate Fritz Reiner with Chicago in 1955. Relistening after a long absence, I find the performance too well-groomed, too predictable in almost every way. George Szell in Cleveland, stands up much better to the test of time. Neither can be faulted for emotional indulgence (that would be Bernstein, I guess). And if it’s grooming you’re after, the name’s Karajan and the presentation is immaculate.

Not to be overlooked is Charles Munch, a strong favourite of Steve Rubin’s in New York. Leonard Slatkin, who contributed yesterday’s post, offers further recommendations in Carlo-Maria Giulini, who does lyricism like no-one else, and David Zinman who strikes a perfect balance between historical fundamentalism and present-day post-modernism. Amir Mandel in Tel Aviv reminds me of the forgotten merits of the deceptively understated René Leibowitz with the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra in 1961, a performance that somehow brings out in the first two movements the pastoral colours of the previous symphony.

We’re getting close to the quintessence and space is runnign out. I have much to say about Evgeny Mravinsky‘s brutal Russian way with Beethoven – Mikhail Pletnev is a far better option – and I shall have to save it for another occasion. I have also been sidenlined by the highly praised though irredeemably dull Ernest Ansermet with his well-polished Swiss orchestra and the unfailingly intriguing Jascha Horenstein with a lackadaisical French national ensemble.

Close as we are to a resolution, we have run out of space. I shall have to conclude this discussion later today.

Stay tuned. Ultimate resolution coming up…. here.