Are we wasting our time on Beethoven’s 10th?

mainWelcome to the 32nd work in the Slipped Disc/Idagio Beethoven Edition

Beethoven’s ’10th’ symphony

Musicians and computer technicians are presently racing against the clock to produce a completion of Beethoven’s tenth symphony, using artificial intelligence tools. ‘Robots pitch in to finish Beethoven’s Tenth,’ ran the headline in the Times’s foreign pages and that’s about all we can report about it until the results are performed at an orchestral premiere in Bonn on April 28.

Before you get too excited, let’s examine the backstory, and sample the existing recordings of this contentious, possibly spurious work.

The first twitchings of a tenth symphony stirred in the mid-1980s when a British musicologist, Barry Cooper, produced 250 bars of sketches supposedly written by Beethoven in his final weeks. He offered it early in 1827 Beethoven to the Philharmonic Society in London and the sketches that Dr Cooper worked on were approximately as far as he got before death intervened, on March 27 that year.

Cooper, a lecturer at the University of Aberdeen, collated the sketches into a 15-minute orchestral movement with three subsections – Andante – Allegro – Andante. He thought there might also exist some ideas for a scherzo second movement, but these were not developed enough for realisation. Amid some musicological scepticism from jealous colleagues, Cooper produced a score that was recorded by two different orchestras and conductors, the second of which was accompanied by a lecture from Cooper explaining what he had done.

You can listen to the lecture here.

Cooper’s movement was premiered in London in October 1988 by the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra, conducted by the former Vienna Philharmonic concertmaster Walter Weller, under the auspices of the Philharmonic Society. Learned opinion split down the middle. One newspaper critic, who wrote that the ‘music sounded half formed’, was the composer Anthony Payne who went on himself to make a completion of Edward Elgar’s third symphony. Payne did, however, recognise that there were ‘fresh and fascinating things’ to be heard in the Cooper score. Within a week, a second performance was given by the American Symphony Orchestra and Jose Serebrier at Carnegie Hall. After that, interest faded and there have been few revivals – until the present Beethoven anniversary year when the work is being dusted off again for public contemplation.

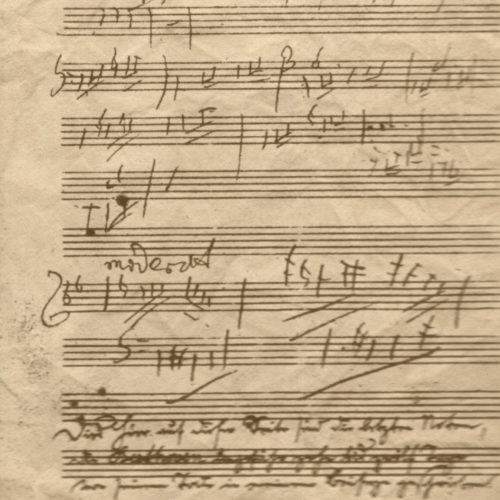

Once the musigologists stopped squabbling it emerged that a violinist called Karl Holtz, who worked as one of Beethoven’s copyists, left an account in which he reported hearing the composer play through some of his material for the tenth symphony at the piano. There is also an archived sheet of music (above) on which Beethoven’s close friend Anton Schindler wrote: ‘These notes are the last ones Beethoven wrote approximately ten to twelve days before his death. He wrote them in my presence.’ That amounts to fairly compelling proof that Beethoven had another symphony in mind as he died, and that these materials were part of it.

So, is it the symphony as it stands worth hearing, and does it advance our understanding of the greatest mind ever to be applied to music?

There is no simple answer to these questions.

Two recordings exist. One is conducted by Weller with the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra on Idagio (listen here). The other was rushed out by the London Symphony Orchestra, conducted by the blustery Wyn Morris, once referred to as ‘the Welsh Furtwängler’. His performance, archived on Youtube, starts out in a more exciting and emphatic fashion, but loses whatever thread there is in the score and threatens at two or three points to unravel altogether. Weller, in Birmingham, is measured, coherent and sometimes convincing.

The tentative nature of the opening takes some getting used to. Beethoven, so assured in his symphonic statement, appears to be feeling and fidgeting around for something new to say. He falls back on familiar phrases, from the ninth and sixth symphonies, and in the middle section on big-gun bluster from the third and fifth. For the first time since the second symphony, he’s taking us back rather than forward. Was the tenth symphony to be a kind of summation of his symphonic life? We can but speculate. The more you listen to Weller and the CBSO, the more the material seems to be pre-used. At 8:45, it’s the finale of the Ninth, around the 14-minute mark, it’s all Pastoral Symphony.

You have to listen in between the fumblings for a big new theme to hear – at 08:30 for instance and again at 11:10 – that Beethoven is reaching into some deep, dark silence for a sound world he cannot access. And every now and then he draws on the new language of the last string quartets to startle us with hints of atonality. Weller, who had his own string quartet, is acutely attuned to these late parallels. He may have been too subtle and thoughtful an interpreter to achieve popular appeal, but his career around the UK – especially in Scotland, where he was commemorated as principal conductor with his picture on a £50 banknote – did not go unappreciated. It may be that this recording is Weller’s greatest contribution to musical history. I urge people to listen to it at least three times to find their own meanings. The special quality of the fragments of the tenth symphony is to encourage you to build your own Beethoven.

Walter Weller died in June 2015, at the age of 75.

Time for a rethink.

We are definitely wasting our time on Beethoven’s 10th. The same goes for Elgar’s third and the last movement of Bruckner’s 9th. OK I have enjoyed listening to Rattle with Berlin Philharmonic playing four movement version of Bruckner in Amsterdam, but one enjoys anything from such a combination, just for the sound itself.

And on Mahler’s 10th too – all the 48 versions of it!

Ok, but let’s forget about Mozart’s Requiem as well. I would argue that there’s more ‘Mahler’ in the Cooke Version of Mahler’s tenth symphony than there’s ‘Mozart’ in Mozart’s requiem.

And Schubert´s Unfinished !

I actually like that one. Mazetti 2 is probably my favorite version.

Of course we are wasting our time. There was hardly anything of it in the first place. Leave well alone!

The best Beethoven 10 was written by someone else:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VqrF7Luxwyw

John, I agree, except with a different “B:” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5HgqPpjIH5c

Possibly….. but that B is from a different tradition. I stick to my own B. Your B is, by the way, an incredible masterpiece, especially the 1st mvt. Never tire from listening.

The research team of Dr Hofstadter from the Music Faculty of the Texas Institute of Technology has revealed that Beethoven had discarded his sketches for nr 10 because they were not up to his standards, and had begun a nr 11. The full manuscript score was, however, burned in the stove by his housekeeper in a rage of revenge for having been treated particularly badly that day. According to indications written in one of his notebooks, later-on suppressed by B’s secretary Anton Schindler, Beethoven had first experimented with a new type of music in his late quartets before embarking on his nr 11. As described in the TIT Journal of Extensive Musicology (issue 8th January 2016), Schindler felt guilty over the disaster since he had strongly recommended the housekeeper who was his niece. It appears that the work would have sounded like follows: mvt one: opus 132/1, mvt two: opus 130/3, mvt three: opus 127/2, and for the finale opus 133 (Grosse Fuge). It appears that Beethoven was never informed about the burning of the score and had been told by Schindler that it had been sent-off to the publisher. Fortunately for Schindler the composer died soon afterwards.

I can find no evidence of a “Dr Hofstadter”, a “Texas Institute of Technology” or a “Journal of Extensive Musicology.” It sounds like you just made this story up on the spot.

We might add Sibelius’s 8th Symphony to the list of might-have-beens-that-somewhat-are, depending on what source you believe.

Time to stop obsessing over Beethoven! He was not the greatest composer who ever lived. There are so many others who need and deserve attention. To even think of using computers to compose classical music is unthinkable.

“He was not the greatest composer who ever lived.”

Of course entirely true. Above a certain level, there are no longer any meaningful differences in artistic quality.

The cause of the Beethoven Cult is the symbolism of modern man in the context of Enlightenment society. All the predicaments of modernity are to be experienced in his music, but in musical terms.

While it isn’t clear what “greatest” means, if anyone is “the greatest” then Beethoven is “the greatest”. The modern symphony orchestra was created in the 19th century largely to play the music of Beethoven, and the many 19th and 20th century orchestra pieces where written so that those orchestras had something else to play. Without Beethoven, there probably would be no orchestras and no standard repertoire.

It may be of interest to not forget that Beethoven did NOT design the symphonic performance culture, dit NOT secure his central place in a canon, and has NEVER instructed musicians to neglect other composers’ works. He wrote his music in the irrational belief that it was somehow important that he did so, ignoring the reality of music life around him where Rossini was the star of the day. But I’m sure he would object to his works being a deterrent for other composers, which would have been contrary to his world view.

Also I’m sure he would be contemptuous about performers using his works merely as a vehicle for narcissistic career building and ‘ego expression’.

http://subterraneanreview.blogspot.com/2016/01/notes-on-beethoven.html

I don’t care one bit about the Beethoven 10th – it’s interesting, but that’s all. But as to Walter Weller, he was terrific, but for some reason too often dismissed. I really enjoy his Beethoven cycles on Chandos – both the symphonies and the concertos. And his greatest contribution to the world of recording was the set of Prokofiev symphonies that came and went all too soon on CD. I wish Weller had lived longer, I know he had some Mahler in him.

Stuff and nonsense.

An absurd undertaking.

Someone should present the sketches AS THEY EXIST, like Harnoncourt did with the 4th mvt. sketches of the Bruckner 9.

Yes.

I often ask myself if we are wasting our time on Beethoven’s 9th…

Surely you do.

this is a winner of a sentence

“He offered it early in 1827 Beethoven to the Philharmonic Society in London and the sketches that Dr Cooper worked on were approximately as far as he got before death intervened, on March 27 that year.”

I had just arrived in Buenos Aires on tour, and before I could check in at the hotel the clerk said”there is a phone call for you from New York; they’ve been holding for an hour waiting for yourarrival”. It was the chairman of the American Symphony Orchestra, saying “for your seasonopening concert with the ASO at Carnegie Hall, how would you like to have the US premiereof Beethoven’s 10th Symphony next week?”. My answer was immediate: “there is no 10th”.”It was just recorded by the London Symphony” was the reply. I said I would need to investigate.I called my friends at the LSO and they just giggled. I called the conductor who had just recordedit, my friend Morris, and his only comment was “my banker was delighted”. The score was sentto me over-night, and it took only a few seconds to realize this “completion” of some sketcheshad no business being attributed to Beethoven as a complete symphony. My reply to the ACOwas “this is a musicologist’s interpretation of what might have been, but it doesn’t merit aperformance”. The replay from the ACO’s chairman was “if you do not wish to perform it, wewill give it to the following conductor, who has already asked to do it”. Child psychology worked.The day of the Carnegie Hall concert Japan TV chased after me to comment about the music,and I was quite open with my impromptu reply: ” Beethoven must be turning on his grave”.Isaac Stern came to the dress rehearsal and we chatted afterwards. We were in agreement.Jose Serebrier

Voilà! Some innocent sketches exploited for commercial reasons, showing to which extent so much of the classical performance culture has turned into a business instead of keeping its format as an art form.