Do atheists write the best sacred music?

mainFrom the Lebrecht Album of the Week:

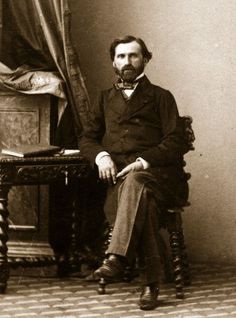

As proof that the Devil has the best tunes, it is an established fact that atheists write the best religious music. Verdi, Elgar, Saint-Saens, Janacek, Ravel, Vaughan Williams, Britten… the list of unbelievers who wrote great sacred works extends to the limits of the known universe. And while we know little of Rossini’s state of faith, it is safe to assume that a man of his dedicated hedonism was not one of the godlier composers.

His ‘little mass’….

Read on here.

Et pour lire en francais ici:

Comme pour montrer que le diable fait ce qu’il y a de mieux, les musiciens athées composent sans contredit la meilleure musique religieuse. Verdi, Elgar, Saint-Saëns, Janáček, Ravel, Vaughan Williams, Britten… la liste des incroyants qui ont écrit de grandes œuvres sacrées s’étend jusqu’aux limites de nos connaissances. Et bien que nous ne sachions pas grand-chose des croyances de Rossini, il n’est pas fou de supposer qu’un homme aussi hédoniste n’était pas le plus dévot des compositeurs….

Lire encore ici:

See also: Is classical music Christian?

Comments