Haunting memories of Yevgeny Mravinsky

mainWe have been sent a fascinating memoir by the sculptor Gavril Glickman (1913-2003), a close friend of the Lengingrad music director Yevgeny Mravinsky, an aloof figure who premiered most of the Shostakovich symphonies.

Here’s a translated extract:

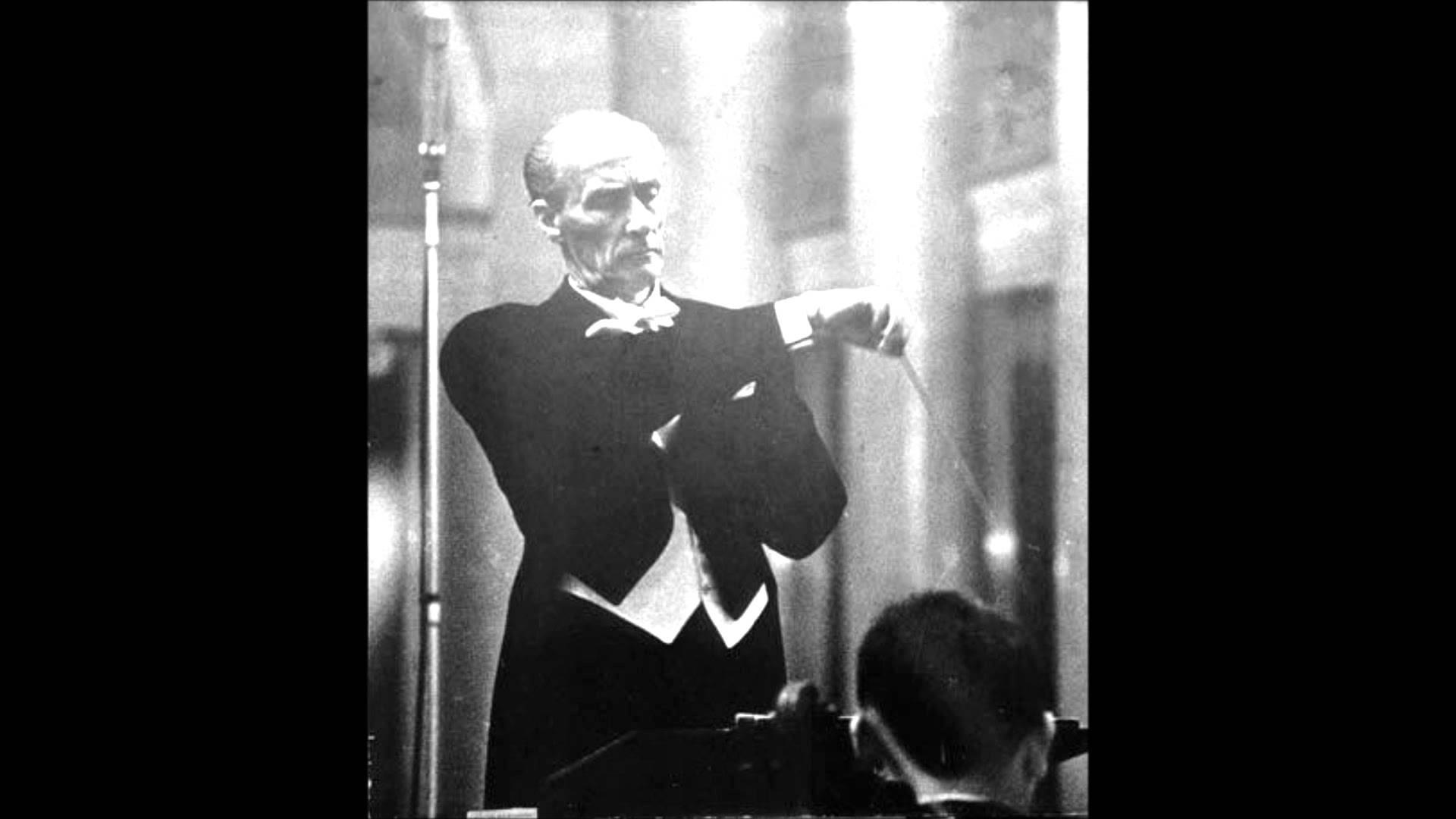

With the famous conductor Yevgeny Alexandrovich Mravinsky, I was connected by many years of friendship. The popularity of this successful, world-famous maestro was very great. The audience was fascinated by the tall, handsome man, tightened in an elegant suit, when he stood on the stage in front of the orchestra. I have watched on many occasions how Mravinsky, with a fluttering gray hair, an impenetrable face and cold eyes, indulges condescendingly and casually in front of the crowded hall. As now I see his well-worked-out barely perceptible smile during the bow, when even the party bosses in the government box of the Great Hall of the Leningrad Philharmonic heartily applauded their favourite.

In the finale of the concert, the hall usually got up, and Eugene Mravinsky was brought baskets of flowers … Even poor students threw modest bouquets on the stage. And when the orchestra left the stage, the public stood for a long time in front of an empty stage, and the conductor gave her one more, the last exit … It looked very impressive: the graceful figure of the maestro against the background of the organ, in a low bow of gratitude for recognition. A little later, in the crowded Blue Room, exhausted, in a fresh sparkling shirt, the famous conductor did not very generously give autographs. And then in a narrow circle of composers, musicians and the closest people, he once again condescendingly accepted compliments and delights … And even far after midnight, Mravinsky’s cozy apartment was ringing. Forgetting about the dream, the maestro gave orders about the upcoming rehearsals, concerts,

Could the fate be greater and more beautiful? In the Philharmonic, wherever you look, there were his big photos everywhere. In the foyer, an exhibition was displayed showing Mravinsky’s path from student years to the heyday of glory. Here you could get acquainted with the foreign press about him in Russian translations, with brilliant compliments … The image of the maestro was whimsically and enticingly supplemented by numerous oral stories about him: about his mystical moods, about the fact that this “favorite of Smolny” is very religious, that he constantly donates money to the church, strange stories about a big picture of a wolf’s muzzle with eyes full of melancholy and sadness that hangs in Mravinsky’s apartment … This was (and maybe, I thought sometimes, it was not at all!) conductor Yevgeny Mravinsky – the pride of Soviet music. And for me, not only before our acquaintance, but then this man was in many ways a mystery. And it became creepy when dark mysteries and contradictions of his soul opened before me.

I accidentally managed to take a small photograph to the West. In the picture taken at the Composers’ House in Komarovo (not far from Repin’s “Penates”) – Mravinsky, his sculptural portrait and myself. Mravinsky was photographed at a time when he seemed to be trying on his sculptural image. Evgeni Alexandrovich lived in a cottage with his wife, Inna Mikhailovna Serikova, who soon died of bone marrow cancer. In my little “Muscovite-401” there were always stretchers, paints, plasticine. And when we met with Mravinsky, I always tried to capture his extremely expressive face and figure. Evgeni Alexandrovich was very friendly towards my work, and I had no material interest, and I worked easily and freely.

Much weakened, Inna Mikhailovna went out on warm evenings from the cottage, and Evgeny Alexandrovich tenderly supported her. They approached my sculpture, watched. Inna Mikhailovna, animated, praised it. Eugene Alexandrovich was wearing a warm, red square Scottish jacket, and next to him the pale, almost otherworldly Inna was illuminated by some heavenly beauty. Later, remembering these days, I painted her portrait – “A Woman with a White Cat”.

Near the House of Composers was the dacha of N. K. Cherkasov. Evgeni Alexandrovich sometimes left for a short time to his friend of youth – he called him Kolka. I stayed with Inna. One day, Mravinsky returned from the Cherkasovs late at night. It was a stifling night. A lot of white butterflies struggled frantically against the glass of the veranda. Evgeny Alexandrovich came a little tipsy. Blushing with rapid walking, thin, fit, tanned, with a flowing head of hair, he embraced me and shouted: “I’m now like Siegfried!” But these rare happy evenings with elevated mood were replaced by gray, sad mornings. Already for many years he took a lot of sleeping pills at night. Mravinsky told me that he was repeating himself, waking from a heavy dream: “In the morning, Schema, in the evening, fluids.”

Inna weakened more and more. Sometimes I had to bring nurses with equipment from the Institute of Blood Transfusion to my car. The doctors’ consultations came. She was cheered, but Mravinsky was told the end was near. Soon the patient had to be transported to the city. They lived on Tverskaya Street, near Smolny, in a small two-room apartment. Evgeni Alexandrovich introduced me to a tall, athletic-looking blonde. Introducing this flute player to the philharmonic orchestra, he said: “This, Gabriel Davidovich, is our real man.” He hinted at the negative attitude of the young woman to “Sovdepie” and “hegemon” (the characteristic words of Mravinsky). A modest, helpful woman appeared in the house, who carefully looked after the sick Inna. She called me once in early August at five o’clock in the morning.

I immediately got into the car. It was a very warm and quiet morning. Quickly rushed to the Mravinskys. Inna lay on the bed, majestically pacified, asleep with eternal sleep. She had no traces of suffering on her face, she retained her former beauty. A brown silk handkerchief tightly pulled off his head and jaw. Especially I remember the swelling of her tender mouth. Mravinsky was gloomily calm. There were no tears on his face. I did not stay long; only asked Yevgeny Alexandrovich whether we would remove the mask. “No, do not,” he replied. I went to my workshop and immediately began to sculpt Inna on her deathbed. For about 12 hours I returned to Mravinsky. The apartment was filled with people: musicians, artists, acquaintances. Inna lay in the coffin, its lid propped against a wall on which Yevgeny Aleksandrovich’s portrait hung. It was symbolic. Inna’s father – elderly, deaf, gray-haired, with features carved out of a dark tree, stood next to his daughter’s body, completely detached from all around him. Evgeni Alexandrovich was in a black suit, with a tie.

It was hot weather. At five o’clock the funeral procession moved to the Theological Cemetery. At the front door, in the street stood a tall, thin Cherkasov in a tightly buttoned cloak, silent and lonely. The funeral did not last long. No speeches. With difficulty, they carried the coffin past closely-fitting monuments to the dug grave. Yevgeni Alexandrovich stood at Inna’s headboard and with his long moving fingers mechanically shook off specks of dust that settle on her white attire. The coffin was closed and lowered into a deep pit.

We came back to Mravinsky in the office car of the Philharmonic. The door was wide open. The apartment had been washed and cleaned, the table was laid. The wake was short. Everyone left without saying a word.

Soon Evgeni Alexandrovich went to Ust-Narva, where he rented a room, and in the autumn he was in the city, rehearsed and gave concerts. Near the House of Peter I was a large house. Evgeni Aleksandrovich was given a large apartment there, he had all the regalia: Hero of Socialist Labor, a laureate of the Stalin and Lenin Prizes.

By this time he had a new wife. Evgenie Alexandrovich told me that Inna asked him to marry this woman. The apartment had stylish furniture. Inna’s favourite cats, as she called them, “kisans”, occupied a place of honour. They even had a separate lavatory. The days were smooth and relatively calm. In the evenings, Mravinsky and his new wife were busy with at the ouija board. Inna spoke from the other world: “Darkness will dissipate, there will be light,” “Prepare for the meeting. Everything will be blue and pink.” Evgeni Alexandrovich asked me not to tell anyone about the sessions, but everyone in the city knew about it….

More here.

But: Was Mravinsky really #1?

I met a Russian viola player near S.F. who had played under Mravinsky for years. Apparently, he was quite a tyrant. He certainly got results. The viola was much happier here.

“viola player”, obviously.

Mvravinsky´s 2nd wife, the flutist Alexandra Vavilina, was a significant figure in the latter part of the Maestro´s career. Mention of her here is a little confusing.

She was the first and the only woman in the Leningrad Philharmonic at the time. She was Principal Flute and she was not only Mravinsky´s wife but also a close friend of Shostakovich. She performed in the premieres of Shostakovich´s later symphonies.

There are videos of her playing under Mravinsky and she is very clearly not blonde, as the author above mentions. She is a solidly built brunette, always with her dark hair pulled severely back in a bun. To my knowledge she is still alive. There is a lovely photo of her embracing Ricardo Muti after a performance with Chicago Symphony when they toured in Leningrad several yrs. ago.

Alexandra Vavilina, beside being a flutist and Professor of Flute at Leningrad Conservatory, is also an accomplished and outspoken writer. She is frequently quoted in books on the life of Mravinsky. Although very little of what she´s written is available in English, from what little there is, she appears to be a dominant and opinionated personality who has had quite a bit to say about Mravinsky.

It´s a shame that the author above doesn´t have much to say about her and that what he says is incorrect and not especially flattering.

Thank you for this information. You may need to read the rest of the article.

Thank you, Norman. I have read, now, the full article above. While it´s a marvelous account and glimpse into Mravinsky´s life during a specific time period, it´s just one chapter of the brilliant conductor´s life.

The author of this memoir, Gavriil Davidovich Glickman, sculptor, artist and close friend of Mravinsky and also an acquaintance of Shostakovich, left Leningrad in 1980, emigrating to Germany, where he died in 2003. By his own account, he lost contact with Mravinsky several years before his departure.

So while Glickman´s account is an exceptional and intimate memoir of Mravinsky until the mid 70´s, Mravinsky´s life and career carried on full force until his death in 1988.That´s a whole new chapter, a decade, at least, that Glickman was not privy to.

Fact checking a bit further, with credit due to online excerpts from Gregor Tassie´s biography of Mravinsky, “The Noble Conductor”, it appears that Imma Serikova, the wife of Mravinsky who Glickman painted and sculpted and eulogizes in this memoir, while indisputably the love of his life, was not his first or even his second wife.

His 1st wife was Marianna, relegated to the annals of forgotten history. His 2nd wife was Olga, who was placed in the uncomfortable position of being married to Mravinsky while he kept Imma Serikova as a mistress quite openly in an apartment across town. This went on for 4 years – 1956 -1960. Olga was convinced that the affair would pass and remained married to him. She continued to appear at concerts and public functions as Mravinsky´s wife, while it was common knowledge that Mravinsky was keeping Imma as a mistress. In 1960 Mravinsky finally was able to get a divorce from the beleaguered Olga and promptly married his true love, Imma.

In Glickman´s memoir (I believe it´s in a later section not translated above), Mravinsky complains heartily about how much he had to keep paying his 1st wife (presumably this was Marianna) when she could be “knitting sweaters” to make her own living.

Meanwhile, along comes the dynamic, ambitious and outspoken flutist Alexandra Mikhailovna Vavilina (b. 1928). A strong personality and a determined professional, she was appointed by Mravinsky as Principal Flute of his Leningrad Philharmonic in 1960. She was the only woman in the orchestra. She can be seen clearly in Mravinsky´s post 1960 videos: a large austere woman, with her dark hair pulled severely back in a tight bun.

Mravinsky had just married Imma Serikova in 1960, and the personable Alexandra became close friends with both Imma and Mravinsky. She also became part of the close-knit circle of friends of Shostakovich. She became an outspoken advocate for Mravinsky. When he refused to premiere Shostakovich´s Symph. 13, it was Alexandra who came forward to the press to explain that there were no political motives. The refusal was due to Mravinsky´s grief over the grave illness of his wife Imma. No. 13 was premiered in 1963. Imma died in 1964.

Imma, knowing her end was near, made it clear to Mravinsky that he should marry their close friend, the flutist Alexandra Vavilina, after her death. As Mr Glickman indicates in his memoir, Mravinksy married immediately after Imma died. The woman he married, his 4th wife (correction from my previous post above), was the “tall, athletic-looking” flute player he´d mentioned earlier, the flutist Alexandra Vavilina. She most definitely is not blonde, though as he describes.

Alexandra Vavilina reigned as Principal Flute of Leningrad Phl from 1960 until just after Mravinksy´s death in 1988. She retired in 1989 and has served as Professor of Flute at St. Petersburg Conservatory (another correction from my previous post.). During that time, she was featured as solo flute on Mravinsky´s recordings, most notably Apres Midi.

The chapter of Mravinsky´s life which included Alexandra Vavilina was not included in Mr. Glickman´s memoir because he´d already emigrated to Germany. For flute players everywhere, it´s an important chapter.

Alexandra Vavilina is, as far as I know, alive and well, and continuing to share her knowledge and legacy of her famous husband. In March 2018, an impressive ensemble of flutists, led by the international soloist Emmanual Pahud, presented a concert of the ¨”Flute Ensemble of the MariinskyTheatre” in St. Petersburg honoring Alexandra Vavilina Mravinskaya´s 90th Jubilee. https://www.mariinsky.ru/en/playbill/playbill/2018/3/11/3_1200

Alexandra Vavilina was his fourth wife, and she celebrated her 90th in February this year.

Alexandra Vavilina is still very much alive, and indeed she celebrated her 90th birthday in February this year. She still lives in the flat she shared with Mravinsky, and where he died, looking onto a beautiful view of the Neva river, facing the Summer Gardens and near the house in which Peter the Great lived. The flat is still adorned by pictures of Mravinsky and many of his posters, and there is still a large cat who usually annoys any visitors, and who is the pride of Alexandra Vavilina. She still takes pupils at home and attends concerts at the Philharmonic and Gergiev always invites her to new productions at the Mariinsky. Sadly there is no plaque commemorating his living there, albeit there are plaques for other celebrated people who lived in the same building.

Sorry I forgot to mention that Alexandra Vavilina was Mravinsky’s fourth wife.

Mr. Tassie, thank you for sharing your insights on Mravinky’s 4th wife, the flutist Alexandra Vavilina! The flute community knows so little about her. Can you tell us anything more about her? Is she as dynamic and outgoing a person as she appears to be from her writings? What, do you think, was the basis of her connection with Mravinsky? She is not a great beauty, as was Inna, his 3rd wife. I’ve heard criticism of her playing, at least later in her career. What was the attraction?

What do you make of the sculptor Gavriil Glickman’s comment in his memoir which Mr. Lebrecht published when Mravinsky introduced her as “the real man“ of the orchestra? And why does he say that she was blonde?

Do you know if she is in good health now, and lucid? It would be fascinating to hear her recollections of her life with Mravinsky.

Thank you for any insights!

Quick correction. I referred to Mravinsky´s 3rd wife as “Imma”. Her name was actually “Inna” Serikova.

What an honor to hear from you, Gregor Tassie!

Mr. Tassie, musicologist, scholar and writer, is the author of the 2005 biography of Yevgeny Mravinsky, The Noble Conductor, https://www.amazon.co.uk/Yevgeny-Mravinsky-Conductor-Gregor-Tassie/dp/0810854279

Excerpts from his book about Mravinsky are available online and I have found them enlightening and fascinating. I, for one, will be ordering the book.

Mr. Tassie has also authored –

Kirill Kondrashin : A Life in Music – 2010

Nikolay Myaskovsky : The Conscience of Russian Music – 2014

all published by Rowman and Littlefield

Thank you for your praise. In response to your questions, may I write that i first met her in 2001, and it was she who suggested i write a book about him, she gave me access to all his diaries, letters, personal photos, etc. I found her an amazingly forthright person, very sharp in her memory recall, and she is very much a guardian of his legacy. She had a previous husband, who she loved very much, who died in a car crash in the 1950s, at that time she was principal flute in the ‘second’ orchestra which Mravinsky saved from disbandment. The person with whom Mravinsky dealt with in stopping the disbandment was Inna Serikova. They met around 1953, when Mravinsky was still married to Olga, his second wife. They lived openly together at the time. Alexandra Vavilina was a friend of Inna Serikova, and at the time of her final illness, Vavilina was one of the ladies from the Philharmonic who helped Mravinsky’s household during this prolonged illness. Vavilina’s hair is light brown, perhaps she may have died it when she was younger. Serikova didn’t want Mravinsky to be left alone and encouraged Vavilina to look after Mravinsky after her death. Vavilina was much more than a housekeeper for Mravinsky and it wasn’t until 1967 that they were married when Mravinsky moved to the house on Petrovsky embankment. There was a moment when Mravinsky tried to commit suicide and it was Vavilina who stopped him when she found him with a revolver in his study. As far as I understand, throughout their life together they looked after each other, she met with Party bosses to try to stop more sanctions against him when he refused to sign petitions against Solzhenitsyn, etc. Mravinsky refused to see anyone from the Party, and there were periods when he was stopped from touring and she found friends in Estonia and elsewhere to look after him when she toured with the orchestra.

Today she is still alert and sharp, and takes an interest in many things, she has criticised privately some famous people in the city, and keeps her flat as a museum to Mravinsky. There are concerns as to what will happen to this flat when she is gone, and complains that she has so small an income. I have often thought about trying to try and get someone to grant state help to keeping the flat as a memorial to the city’s greatest conductor. Perhaps others might be better placed to help. Every week she goes out to his grave and tidies it, there is a place for her there, and Serikova is buried in the same plot. She is a remarkable woman.

Wow! Thank you for sharing these amazing recollections and insights, Mr. Tassie! Your observations truly humanize both the great Mravinsky and also Alexandra Vavilina.It’s like a chapter in history coming alive! So looking forward to reading your book and to learning more about Mravinsky!

Sorry I forgot to mention Alexandra Vavilina as a flute soloist, I can’t comment about any perceived decline about her playing in the orchestra, but I do now that she was sacked by Mravinsky’s successor because he thought she was spreading gossip about him in the orchestra. She was told she was sacked at the first rehearsal session in front of the whole orchestra, several other long-standing members also left partly in protest and because they no longer wanted to work there anymore. Vavilina was offered positions at Fedoseyev’s Moscow Radio Orchestra and at the Kirov Theatre however she decided to give up her career and devote herself to teaching.

He was most definitely a “tyrant” which was not that unusual in itself, since in the middle of last century several of the most successful European-born maestros behaved in dictatorial manner to a various degree, e.g. Toscanini, Reiner, Szell, Karajan. In Soviet Union his tyrannical ways were practically normal and natural because of the country’s strongly hierarchical way of life, and so he continued in this fashion virtually until his last days which ironically coincided almost exactly with last days of the totalitarian empire. He was never close to being a dissident, but at times he could be rather firm toward government bureaucrats when he felt that he needed to acquire some minor perks for himself and occasionally for his orchestra too. He knew he could afford that risk because he was a very valuable commodity for the government – a world class musician who was a reasonably loyal ethnic Russian, while most other leading soviet classical performers of his generation (Gilels, Richter, Oistrakh, Kogan, Shafran, Rostropovich) were not. Another important aspect working in his favor was the fact that being a member of “his” orchestra was not only highly prestigious but also tremendously advantageous financially for Soviet citizens because the orchestra traveled abroad regularly including in the West and in Japan while this was something that was beyond reach for 99% of their compatriots; it gave those musicians a chance to see the world but also to purchase foreign goods that were unavailable in Soviet stores for themselves and their families and quite often even to sell some of what they bought for huge profit on black market. Therefore any vacancy in that orchestra was highly sought after that giving the boss plenty of leverage that he needed to keep orchestra members fully obedient and subservient to his every whim and wish. No wonder that for the last four decades of his long career he hardly ever conducted any orchestra other than “his own”: it was impossible for him to duplicate anywhere else those conditions to which he became fully accustomed with Leningrad Phil.

…highly sought-after, thus giving the boss…

It would be a lot better if you based yourself on facts and not something made up, Mravinsky was no tyrant, his musicians called him Vasya, or Joshua the best English comparison, he socialised with many of his musicians and often drink with them at his home. He was no dictator but certainly could lose his patience with musicians who were no longer able to play as he wished, and he could not sack musicians that he didn’t like because there was a Party committee who had the final say as to was appointed or dismissed. Your account of Soviet musicians liking to go abroad so they could buy and sell sought after goods is pretty unscrupulous, certainly any good musicians wants to show his best as a musician by playing abroad, and the Leningrad Philharmonic were no different but listening to them when I interviewed them only told of their desire to show that their orchestra was the best Russian orchestra and to show the best Russian music, yes they liked walking around London and other cities, but their time was often spent rehearsing and preparing for their concerts rather than rushing around Oxford Street for the latest fashionable clothes to take home. I am afraid you are quite out of touch with way in which Mravinsky’s orchestra operated.

The difference is – you interviewed those musicians while I didn’t have to. Several of them were close friends of my parents and/or parents of my close friends. Stories they told were far too similar to be suspected of being untrue. I might elaborate on that later when I have more time for this.

Sorry it appears your ‘information’ is based on second hand or third hand stories. The stories of musicians becoming peddlers was more the case in the 1980s and later but wasn’t a feature in Mravinsky’s Philharmonic.

Not at all: as a teenager and later, I heard those stories personally from the musicians I knew well, and the practice of selling items acquired in the West was used widely in USSR since at least early 1960s. It is not at all surprising that they did not like talking about it when being interviewed, but I can certainly agree that this was probably only a minor attraction in foreign tours for them: seeing the world and their pride of playing good music so well for foreign audiences may have been first, while opportunity to get quality stuff for themselves and their families possibly second. Also, if any orchestra member (with possible exception of the conductor’s wife) would have addressed YM in any way other than “Yevgeny Aleksandrovich” or maybe some version of “Comrade Mravinsky”, that person would most likely be on the street looking for a new job faster than you can pronounce your own name. It is true that party bosses could use their powers to influence hiring/firing decisions, but it mostly involved the hiring part of it – they wanted to make sure that no suspicious person would join this world-touring orchestra; firings on the other hand did not bother them much because YM was infinitely more valuable for them (because of reasons I mentioned in a previous comment) than any individual orchestra member. So, if he wanted to fire anyone, it was usually fine with them, but of course if they wanted someone to be fired then it was more or less the final decision.