Opera of the Year (2): The one that builds its own instruments

mainComing up at the Huddersfield Contemporary Music Festival (hcmf) in November:

Surely the most visually arresting work of hcmf//’s first weekend will be the World Premiere of Claudia Molitor‘s hour-long Walking with Partch performed by Ensemble Musikfabrik. In 2012, Musikfabrik set out to re-build the visionary American composer Harry Partch’s unique micro-tonal instruments; and for their continuing ‘pitch 43_tuning the cosmos’ project they have commissioned new works by European composers for these impressive instruments in order to give them a life beyond historic reconstruction.

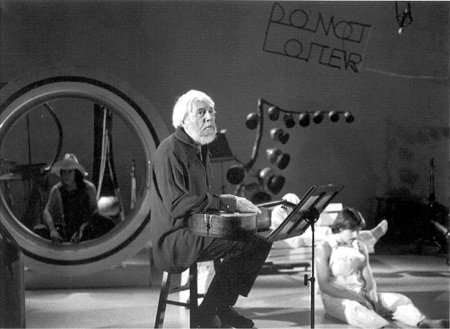

Harry Partch (c) Betty Freeman/Lebrecht Music&Arts

Comments