A partner’s lament for fallen conductor

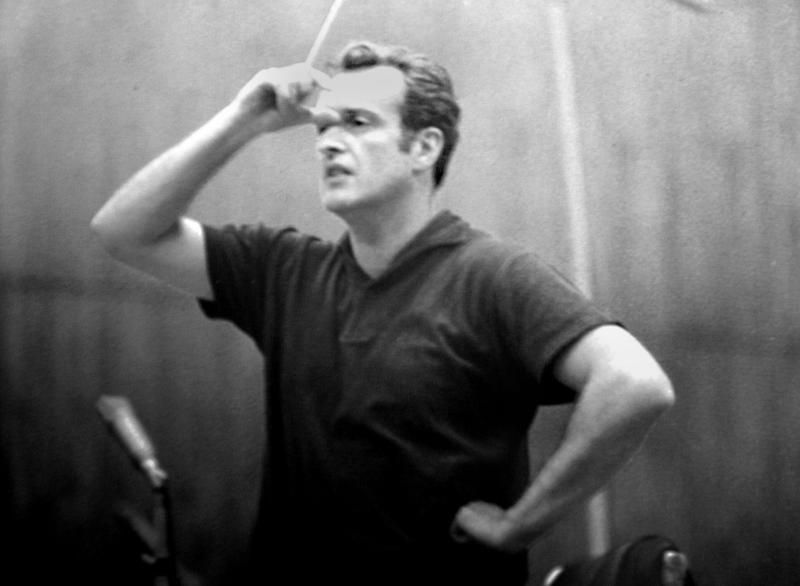

mainAmari Barash was playing oboe in the orchestra when she saw the love of her life, conductor Israel Yinon, collapse and die on the Lucerne concert stage. Two days after Israel’s funeral, she writes for the first time about their life together. A blessing on his memory.

When I first had the great good fortune to perform with Israel Yinon, I was struck by his generosity and light-hearted wisdom; his conducting revealed that he had suffered and overcome untold obstacles to become the exquisite artist and jubilant person he was. Now, seven or more years after that first encounter, I write this in our strangely silent home under the gentle gaze of hundreds of meticulously marked scores. It is a misfortune for all of us that he will no longer coax the secrets and magic out of their pages. For me, it is a singular tragedy to write these words on my 38th birthday, a day like all the days to follow in that he will now accompany me only in my imagination.

Israel collapsed during his first performance of Strauss’ Alpine Symphony, an extraordinarily complex programmatic work representing a climber’s ascent to a mountaintop (with excursions along the way), descent, and contemplation of a majestic sunset. Israel left us just after I played the extended, serene oboe solo in the section entitled “Auf dem Gipfel” (“At the Summit”). He reached a summit of musical euphoria analogous to the peak of excellence and joy he had achieved in life, and then he disappeared from this world.

Israel was best known for his discoveries, revivals, and astute recordings of so-called entartete Musik; despite the significance of his work in that field, though, I believe that his musical legacy lies principally in his interpretive power. He was in every sense a composer’s advocate and immediately endeared himself to those with whom he worked, including Tilo Medek, Hans-Peter Dott, Helmut Lachenmann, John A. Speight, Josef Tal, Thüring Bräm, and countless others. Israel took pride in his ability to draw out his distinctive sound from every ensemble he conducted. He called his work a transfer of energy. As with the Yinon sound, a particular exhilaration was always palpable in the audience during and after Israel’s concerts. The transfer of energy was more than his sound concept; it would never have succeeded without the humanity and vitality that radiated so physically from him. It was temporal, too: Israel often consciously created the illusion of a forward-pushing tempo while in fact maintaining a quite stable pulse. This sleight of hand depended, of course, on the flexibility and freedom of the orchestra, and I witnessed more than one instance (mostly in rehearsals, but occasionally in performances) in which the players’ fears or simple inexperience held Israel back from expressing his vision por completo (a phrase he was fond of using). Even in those moments, though, deep respect and affection blossomed between him and the musicians with whom he worked.

Sometimes Israel puzzled me.

In conversations both musical and otherwise, he often responded in a way so unanticipated that I wondered if he had misunderstood what I had said. But he existed and thought on intersecting points, lines, and planes; he found subtle ways of steering a talk about politics or psychology toward accordions or stereo components while keeping a meaningful thread running through it all. With time I realized that he had opened up new dimensions of thought for me. I suspect that many reading this essay will know just what I mean: Israel offered the prism of his exuberance unconditionally to everyone he met, and he listened too, taking a genuine interest in the remarks and in the spirit of each individual.

May we all find the inner freedom, enthusiasm, and big-heartedness to keep experiencing the musical and human essence of the irreplaceable Israel Yinon.

Dr. Amari Barash

Berlin, 7 February 2015

(c) Amari Barash/Slipped Disc

Dear Amari,

I admire your eloquent tribute to Israel while suffering such a tragic and unexpected loss.

Your father was my mentor for several years in Pittsburgh and in Venice. Without his help, I would not be the happy, healthy person I am today.

He would be proud of the sensitivity and maturity you display in the face of such a loss. He would also be proud of the lovely person you have become and your successful career in music.

You are still a young woman with much of your life ahead of you. You have the strength to carry on and eventually you will be living life to the fullest again.

Best wishes to you,

Margaret Wilson.

Dear Amari,

I looked you up early this morning, curious to see how you have been. I was shocked to see this article from last year. I can’t imagine how difficult this has been for you. Your editorial about your partner was so beautifully written, and so true to everything I knew about you from our days at Eastman. I know we have lost touch for some years, but I’m very proud to call you my friend.

Stephen