Bartók was about to be evicted when he died

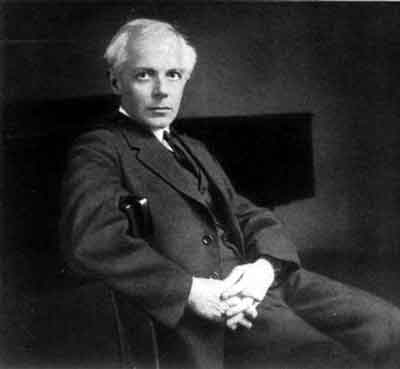

mainChicago psychotherapist Gerald Stein has an original take on Béla Bartók’s mindset as he lay dying in New York in 1945. Bartók himself said he planned to leave the world with ‘an empty trunk’, having given his all.

His musical being, occupied by what he could yet compose had he “world enough and time,” was still overflowing. The European emigre sought to expend everything on the job of life. Spill the suitcase out. Unpack the riches within.

Since he was born with nothing, Bartok believed he should leave with nothing. He saw this as his obligation to himself and his fellow-man: to share whatever “good” or goods he possessed, to reveal the talents nature bestowed upon him and those he developed.

Creative people often feel chosen. Some consider their craft a “calling” impossible to ignore. They write or perform, not only as a livelihood. Indeed, more than a few sustain their artistic aspirations even though they can’t make a living doing it.

Bartok himself was about to be evicted from his New York City apartment at the time of his death. These people persist out of an “inner necessity.” They cannot do otherwise.

Bartok’s notion is no different than the sports heroes who try to “leave everything on the field,” giving their entire capability to the game. And, while most of us are not inspirational leaders, geniuses, or athletes, we can emulate the most admirable of them: to reach for all we are permitted, work hard, and face challenges instead of running away….

Read on here.

Menuhin could easily have offered more than $1,000 to Bartok in the final days of the latter’s life when commissioning the Solo Violin Sonata.

Menuhin said in an interview that Bartok was so scrupulous about money that he didn’t cash the check until the commission was completed. This was when Bartok didn’t have a lot of money. To be fair to Menuhin, $1,000 in 1944 is worth around $15,000 today. Any good biography of Bartok out there to recommend?

It is good that you point out the value of $1000 in those days vs. today, CRWang. Thank you.

The most accessible English language bio of Bartok remains, after all these years, Halsey Stevens’ “The Life and Music of Bela Bartok”.

– best regards, Greg

Still, a bargain from a known composer. Who doesn’t like a bargain?

David Cooper Béla Bartók

Mr. Lebrecht, I read your recent piece on the Critic on music and sports, it is thought-provoking, instructive and very well done. Thank you!

thank you!

The analogy to sports heroes is not quite apt since they have many (100s) millions in the bank and enjoy wide public adoration, which makes their “sacrifice” rather tolerable, vs. the true penniless and starving-artist ending that Bartok n many other great artists endured.

Absolutely true. The comparison is outrageous, as it is outrageous that a man like Bartok had to suffer material hardship. When will society understand that it should be grateful to the great minds who bestow so much value upon the world and add meaning to it, where it is so much lacking? In former times the composer was a mere servant of church and nobility; when he liberated himself from those yokes, the only way to survive was as a competitor in a free market place. Beethoven was saved by three understanding partons, Chopin had to teach silly haute bourgeois girls for status purposes, Berlioz had to write reviews, etc. etc. Wagner was saved by a ‘mad’ king, but almost all other composers had to find other ways of making money which restricted their time for their real work. Why was there nobody of the french upper classes that took on Debussy, so that he was spared the pressures of his publisher, and lived in debt for most of his life? Etc. etc…

In Europe, support from state and foundations took over patronage in the last century and see what kind of music that created. The problems resulting from the liberation from church and nobility have never been really solved.

That’s an interesting romanticized write-off about the lifestyle of a creative artist, that conveniently leaves out how neglected Bartok was, which might have to do with his being evicted from his apartment upon his death.

The whole article says nothing about the neglect Bartok suffered, and that perhaps had he been more honored during his lifetime that he would have felt accepted enough to feel that what was inside him was received.

The great concerto for Orchestra, a mainstay of the repertoire incidentally was only commissioned because Koussevitsky had 500 dollars left over, and it was an afterthought.

I remember reading an article by a conductor romanticizing his connection with Bartok, which actually amounted to as a child living in NewYork he used to throw stones at an old frail man, when he would get out of his car to go into this apartment, years later finding out that was Bartok, and the apartment here mentioned again.

I think you’re referring to a recollection by David Zinman and he threw stones at the windows not the composer……..

Bartok could have taught composition at any school he pleased, and was offered the opportunities. He didn’t feel he was qualified to do so. Bartok gave successful recitals in the U.S. with Szigeti in 1940. He taught Ethnomusicology at Columbia in 1942 and was paid relatively well. He started a series of lectures at Harvard but was unable to finish them due to health.

And in this state, he writes Concerto for Orchestra, one of the great pieces in the orchestral literature.

Béla never got over Ein Heldenleben.

I don’t think everything is as simple as it is being portrayed here. $1,000 was a very large sum of money in the 1940s, when the average annual income was about $1,400. And, Bartok made it very difficult for his friends to help him because he would not accept any money that he had not earned from either composing, teaching, performing, or doing research. At a time, his profile as a composer was not very high in the US except among a small circle of musicians, he was no longer in any shape to perform, and I don’t believe he wanted to teach composition. (Columbia University did pay him out of a separate fund to do scholarly work on folk music.) I may be mistaken, but it seems that a significant amount of his income during his European days was derived from performing. Had he reached out to any number of sources, I think he would have been in a much better financial position. There were people who wanted to help, but he said no.

You hit the nail on the head, Dan P.

Bartok was possibly the most scrupulous of all composers in terms of accepting and being paid for commissions. (Compare him with Debussy!)

And you’re right that he made a significant percentage of his total earnings from performing – he was a brilliant pianist who played not only his own works (he premiered his First and Second Concerti with Furtwangler and Rosbaud, respectively, and those pieces are strictly virtuoso territory), but those of Chopin, Liszt, Debussy, Scarlatti – and many others. Klemperer once stated that Bartok had the most beautiful touch of any pianist he had ever heard.

But Bartok did continue to perform after his relocation to America: for example, he and Ditta played the premiere of his Concerto for Two Pianos and Percussion with the NY Phil and Reiner in Jan. 1943.

What a tragedy it was that only when Bartok’s health was failing that his compositions were starting to be more widely recognized for their quality and performed more frequently.

I believe Bartok is still, to this day, underappreciated as the towering genius that he is.

Debussy preferred to write according to his inclinations and only accepted commissions because of the eternal pressures of his debts. For instance, Pelléas, the Nocturnes, La Mer, Iberia – all milestones of the repertoire – were written without a commission, so they were, in fact, given free to the music world. Later in life, he accepted the Martyre project because of the fee, and only after Diaghilev doubled the fee for Jeux, Debussy accepted it although he found the plot of the ballet ‘idiotic’. Khamma he wrote without any inclination, for the money, and another offer for an opera, from NY, he never delivered but laboured on sketches until he died. Debussy was cornered because his 2nd wife (who fled a rich banker husband) expected a life style he could not afford, and his own tastes for interior decoration were rather more expensive than foreseen. But all of this does not mean he was careless about commissions, he merely wished to encapsulate himself in a sophisticated creative bubble and be left in peace – which the world did not allow.

Indeed, he refused to teach composition, feeling that it would render his own creative work impossible. That’s why he taught piano, not composition, at the Liszt Academy in Budapest.

And he was very wise with that decision. What could he have taught? His mixture of abilities was unique and highly personal.

That seems to be true. He thought that being given money just for being able to compose, was somehow wrong. Which is, of course, ridiculous: such people should be emmerdé with money so that they can be free of care that only creates obstacles. It seems to have been the opposite of the 19C romantic notion of the Great Artist who had a right to be supported by the world, because he gave it so much, this was the way Wagner thought about patronage and of course he was right. I think Bartok’s was an ‘antiromantic’ attitude combined with personal modesty.

His last European abode, a beautiful villa (now museum) on the outskirts of Budapest, is well worth a visit.

Another story is that at his death Bartok had a $1,000 check for the comisssion Reiner arranged through Koussevitzky for the Concerto for Orchestra, uncashed because Bartok considered it slightly unfinished.

Happy memories of mid-20C, when the musical world was almost awash with Bartok’s brilliant music. Now so neglected. So original, although so pervaded by Magyar music and language. One of the 20C greats. The only book I have on the shelf is one published back in 1953!! ( My copy is a later edition. ) The Life and Music of Bela Bartok, by Hasley Stevens. There must be a host of others, and of course, as informative as this book is, there is no substitute to playing and listening to the music. Sometimes an entry in Slipped Disc, Norman, brings back so many memories. The gift from my parents on gaining a place to study music as a 17-year-old was an LP recording of the Concerto for Orchestra. Tomorrow, my Bartok revival begins with taking down my many books of his piano music and getting them under the fingers again. Then all the CDs. Thank you for the reference.

Indeed BB was one of the greats. It is strange that his music is played less today. But as late as the nineties of the last century, orchestral programmers in Vienna and Munich thought the music ‘too modern’ for the local audience’s tastes and objected to have some BB on their programmes. I heard this from a conductor who got this puzzling feedback himself. I don’t want to name names, but it was [redacted].

Bartók’s music is not frequently played these days because it demands rehearsal time that is rarely available and, more importantly, it allows no leeway for fakers. You either conduct it clearly or play it correctly. Otherwise it will literally fall apart in concerts. No surprise the Concerto for Orchestra or The Miraculous Mandarin are no longer “the wonder of the ages.” You cannot learn/absorb these pieces from just listening over and over to a recording. Young conducting “stars” who have never played in an orchestra or were trained by the assorted, parochial and embittered wannabe’s in so many academia posts conveniently steer clear of these pieces because they can’t “dance and emote” their way around them. I am afraid that the same fate awaits other masterpieces like Le Sacre. We will soon know…

Boosey & Hawkes was looking after him, providing funds. Imagine a publisher doing that now.

Nowadays, it’s the other way around.

His son was in the army and sent money to support his father. Bartók put this in the bank, didn’t use it.

If this is true, then Bartok was an oaf.

Perhaps Bartók suffered too much from his own pride — Szigeti, Reiner and other friends had to scheme to find commissions for his music but the composer had to be kept absolutely in the dark about the back story because he would then regard them as charity, and turn them away. We know he worried about how his wife would get along, and that is at least in part why we have the Concerto No. 3 (and why some Bartók absolutists distrust that work, more for its modest stab at being loveable at first hearing than for the fact that Serly had to tidy up the ending).

I agree that this notion that he wanted to leave the world broke because that is just the sort of great man he was seems highly romanticized — almost a parody of a late-1960s hippie’s idea of doing without possessions and how glorious that would be.

Joseph Szigeti has some insights in his autobiography. Some excerpts. “Those who have grown up since the development of the Bartók cult (with recordings of his works filling three and a half pages of the Schwann Catalog) can have no conception of the extent of the neglect. The record industry was probably the worst among the many offenders ….” While in 1930 Bartók wrote rather sourly than his success in London was 20 years too late, Szigeti wrote that that “glimpse of bitterness mingles with his philosophical resignation. He seemed always to be expecting the minimum, anticipating reserve, accepting lack of whole-hearted appreciation. Of bitterness there are few traces.” Szigeti wrote that when Bartók’s folk music work at Columbia was not renewed, the composer noted that if he had to live on concerts “we would really be at the end of our tether” but his major regret was that the work was so interesting.

Szigeti gives ample examples of letters from Bartók, and conversations he had, where the composer did indeed worry about money.

Colin Wilson, the once-popular author, has some interesting (if mostly negative) things to say about Bartók the man in his book “Chords and Discords” and much of it is in reaction to his having read Agatha Fassett’s book, “The Naked Face of Genius” about her own very difficult dealings with both of the Bartóks (she evidently found them, and furnished, the apartment referred to above). Wilson sees Bartók as far less noble and suffering and more self centered and spoiled as a child and like a child, and he recounts Fassett (whose book I have never come across or, obviously, read) as being mostly bewildered by the man and his negativity and coldness.

Where the truth lies I could not begin to say but somehow I cannot accept that Bartók preferred or even accepted dying broke.

Maybe Bartok was merely very defensive, hiding any emotional resonance. There is quite some coldness and negativity in much of the music though: Bluebeard, Miraculous Mandarin, 1st and 2nd pf concerto, etc.

He had a family to look after, though. As I understand it, he wrote his 3rd Piano Concerto very shortly before he died and gave his wife Ditta exclusive rights to play it for several years thereafter. It is less technically challenging than his other two piano concertos, clearly an accommodation to Ditta’s skills. She did indeed perform it widely and largely supported herself in this way for a time.

And what a wonderful work it is. Good music does not need to be difficult to play to be superb. Especially the 1st movement is a wonderful take on Beethoven.

I hear more Beethoven in the slow movement, a clear reference to the slow movement of Op. 132.

Yes, that is true.

But the 1st mvt has echos of Beethoven’s 4th pf concerto (1st mvt), not in terms of material but in the atmosphere and the brilliant lightness of tone.