After Cami, America won’t know who to call

mainTwo months after the 1929 Wall Street crash, most of America’s businesses huddled together for survival into two large corporations – Arthur Judson’s Columbia (CAMI) and David Sarnoff’s NCAC, with Sol Hurok as its prominent talent agent.

Between them, these musical versions of Hertz and Avis carved up America. If Ohio wanted an artist, it rang one or the other.

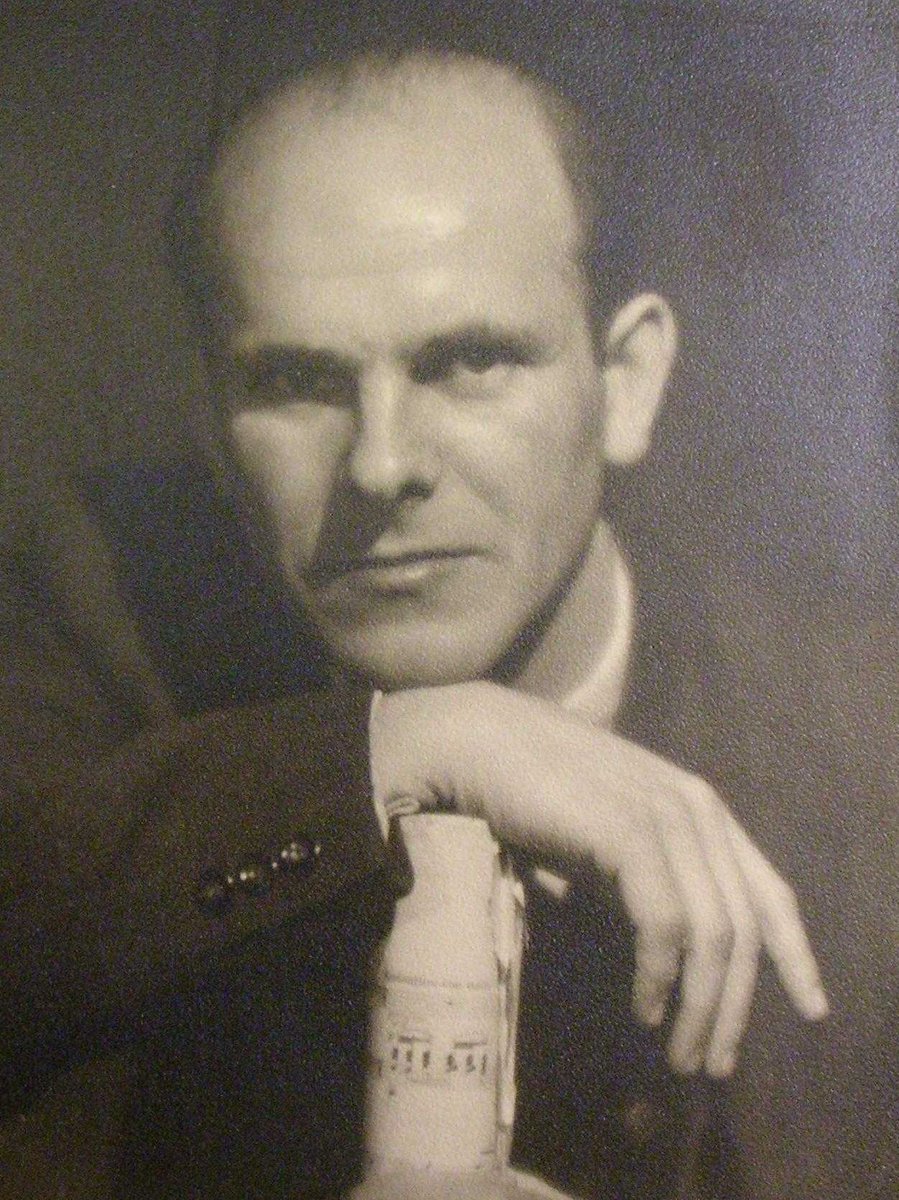

The dominant duopoly ran until the 1950s, when NBC lost interest and Ronald Wilford succeeded Judson. From then on, it was all Cami.

After Wilford’s death in 2015 Cami spiralled into decline, losing key players and Lang Lang’s manager.

Today, is its last day of business.

What happens now?

Musical America needs to rethnk its structures. In a global century, many of its orchestras hire direct from European agencies and many artists manage without an agent altogether. Where is the centre. There is no centre. Even Carnegie Hall is not the destination it was.

The question of how classical music survives in America needs to be addressed right now, and with some urgency. Any ideas?

(For the historical background, see my books The Maestro Myth and Who Killed Classical Music).

I guess they will just search on Google and send an email (or a FB/Whatsapp/Instagram message

I can see much sense in your (apparently) a bit sarcastic thought , any way why not to give it a try 😉 …

p.s. ironically about a day ago I used FB video messenger to talk to one of the best lyric sopranos in the world (by my choice, of course), we discussed some minor issues and chatted a little. What a gorgeous cat she has ( and a dog) …. the connection quality was perfect , so if Covent Garden needs a top-notch singer I can be of help ( with no commission, just for the love of art 😉 )

Yes: get rid of the ‘star’ system, overblown publicity selling mediocrity and get the best quality musicians back onstage, not the most ‘popular’ with the amount of likes on social media. With quality, which is how it started, not this overblown pop system. People want to be moved emotionally. The ‘spectacle’ sale of classical music clearly failed.

Beauty is in the eye of the beholder, they say, and who determines the “best quality musicians”?

Not competitions, of course, not schools, not managers, not critics, then who?

Maybe it’s a good thing. Big companies tend towards monopolies.

Surely CAMI had slipped into decline years before Wilford’s death. The rot had set in before the company gave up its prestigious offices on West 57th Street and moved round the corner to a dingy Broadway office block.

You are 100% right!! It started way before Wilford’s death.

This thing, COVID-19, will end and a new era will emerge. There will be new presenting organizations, new ensembles, and new management companies. Hopefully, many will be run by great BIPOC individuals and collectives and the gifted people today will lead performing arts into a new and different era. It is sad to see CAMI go, as others have folded before them, but they likely had too much power in their day.

They had too much power because that is precisely what Wilford wanted. In a rare New York Times interview in the 1970s he is quoted as saying, “My artists don’t think I’m a sonifabitch, and I don’t care what anyone else thinks.”

Why do you need to mix identity politics into Music?!? What does BIPOC have to do with search for talent? A racist approach to great art. Offensive.

I’d guess international agencies will probably swoop in now – the likes of Opus 3 or Harrison Parrott. As it is, the business for the short term is going to be focused on Europe and Asia, with the U.S. likely to be at least semi-closed through the rest of of 2020-21, and facing much uncertainty beyond that. And if Trump is re-elected, foreign artists may face more red tape or have serious misgivings about coming here. We’ll see.

No work on!!! Too many socialist restrictions; so no income for anybody which means more agency and venue failures. SIMPLE.

Trump will win easily with more support among all the Democrat voters who have turned away from violent, egotistical rioting by the left beginning in 2016.

LEGAL immigrants and workers are welcome just as they’ve always been in the USA.

That’s false: legal immigrants and workers are *not* welcome “just as they’ve always been in the U.S.”

Even before the pandemic, the administration of the orange enemy of the people made substantial changes for the worse.

International artists, their agents, and anyone in the U.S. who wanted to hire them, all know how things have gotten worse and worse for any artist who wants to enter the U.S. to perform, especially in the last four years.

It has become increasingly and substantially harder for people to immigrate, to get work visas, to cross the border, etc.

This was true even from somewhere as benign as Canada.

“Socialist” restrictions (whatever the heck they are) are not the issue. The xenophobic policies of the orange enemy of the people and his minions are.

CAMI was a lesson in greed, avarice and bad management. The smart managers got out and started up their own thing. The smaller boutique firms snatched their talent up and the handwriting was on the wall. What they became will not be missed.

The MET is DEAD as are all other performance houses laying dormant.

NY needs better men than Cuomo and De Blasio to get the state & city cleaned up and operating again. Otherwise the rioters and homeless will destroy what’s left. It may not be a bad thing though. Lincoln Center is a symbol of white supremacy. See San Juan Hill projects to educate yourselves.

Do you really need a manager now to start an account on YouTube and Zoom since that’s where most careers are headed towards……

I guess they’ll be calling more or less the same people, some of whom will be CAMI veterans with new contact information. Tracing the latter has never been easier. The world has gone through cycles of consolidation and decentralization before. What is the big deal?

The more pressing question in my mind is how soon and to what extent people will resume their old concert going habits, which were already in decline.

I don’t know about that Norman. It was nearly always possible for a presenter to book seasons with non-CAMI artists and attractions. I was once on an elevator at the ISPA conference and overheard a very important presenter say to a colleague “Well, I’ve achieved something I’ve wanted my entire career. A complete season with no CAMI artists”.

There was always something very oppressive about CAMI despite the emotional outpouring to the contrary on social media in the last days mostly from former employees who seem to have suffered from some form of Stockholm syndrome. The sort of behavior permitted and often encouraged by their leadership was appalling and abusive.

I’m not quite sure what this article is saying. As Norman observes, people have called European agents directly now since the internet became the preferred mode of communication for most business. The idea that artists need territorial managers is totally outdated, especially when most major artists only really want to play a certain number of venues in North America anyway (let’s say ten opera houses and fifteen orchestras). The truth is that corporate structured artist management companies haven’t worked in a while because the margins are too thin for a secure 3:1 return without paying staff, especially junior staff, starvation wages. Also, companies like Columbia, Askonas, and IMG are likely always cash poor because they front money for what they deem more profitable ventures, like touring. Ironically though, they rely on the more steady income from artist commissions to foot the touring expenses, so likely these companies, which always operate with quite a bit of debt, just can’t pay off these incurred expenses with the severely reduced commissions they may (or may not) be receiving. The companies that have a shot at surviving this are the boutique agencies that basically have no overhead apart from staff. If the pandemic does anything, it will be to break the stranglehold some of the larger agencies have on talent.

This is probably the best thing that happened to classical music since the introduction of recording. Orchestras and other presenting organizations have been financially strapped by their seeming need to pay “superstars” managed by agencies such as CAMI excessively large amounts; the “superstars” then show up and mail in a performance of a warhorse that they have seemingly played 10,000 times. Hopefully, this will open up the opportunity for new talent to emerge, talent that will take more risks with respect to repertoire, interpretation, and building a new and more diverse audience for classical music.

RIght, it seems that Mr. Gergiev can earn a little less than $17M a year!! It will be more than fair. Then we can hear and see more talented conductors on the podiums around the world.

New agencies will emerge when concerts can happen again, but there will be a long tail to this. Orchestras will be licking their wounds as they have cut costs, tapped their endowments (lowering their annual investment yields), and started scrutinizing every cost. The seasons orchestras are currently planning are going to be lighter on big-cost soloists unless they are one of the handful that are a return on investment. But they are the buyers for these kinds of artists, and it will be a buyers market where no one wants to spend much. Expect programming to be far less ambitious, fewer concerti, less commissioning, and a lot more sure-sellers as we all play the hits for a few years.

Funny you should say America won’t know who to call considering CAMI had a much wider representation for other artists and orchestras. And their methods were often more than shady. I think most readers know the debacle of the terms proposed by Peter Gelb on behalf of his mentor Wilford for 2 concerts with the Berlin Phil and Karajan in Taipei. Something like DM600k for the concerts but the promoter also had to

guarantee the showing on Taiwan tv of something like a dozen Karajan videos at an astronomical additional fee. That resulted in a very unflattering front cover on Der Spiegel.

A couple of decades later an Asian orchestra not in China booked Lang Lang from CAMI. The fee was non negotiable and it was instructed the signed contract had to be issued within 7 days. A duly signed contract was dispatched to New York about 10 months in advance of the date.

About 3 months prior to the concert, the orchestra noticed that Lang Lang was billed to play a Concerto in a neighbouring country only 3 weeks beforehand. Doubting that he would tolerate a 3 week gap unless he had lucrative engagements in China, the orchestra tried every means possible to reach his manager at CAMI each time palmed off with secretaries or a receptionist. That urgent contract had never been countersigned by CAMI and he never did fulfil the engagement.

On another occasion when a major violinist had been pencilled for a gala, the organization was unable to proceed and the pencilling cancelled about 9 months in advance. A lawsuit was threatened and a lawyer’s letter received. It was never followed through.

These are just a few reasons why some regard CAMI’s demise with less than the sadness others have expressed!

CAMI’s demise is inconvenient and promising.

Inconvenient in that presenters can no longer make one call and say, “Give us a season,” and in doing so agree to dictation of programming and tradeoffs such as agreeing to book x-number of lesser-knowns in order to access one big name.

Promising in that artists and bookers may develop more direct relationships, yielding more creative programming and/or presentation. Conceivably, artists – especially soloists – could feel less pressure to tour with a handful of warhorse pieces that they may or may not play convincingly (not all violinists were born to play Tchaikovsky). Artists’ concert repertory could more closely resemble the choices made by those who’ve gone “indie,” controlling their recordings on self-owned labels.

In pop music over the last 20 years, the rise of indie singers and bands, and venues and media catering to them and their audiences, have produced a level of variety and creativity unimaginable under the old regime of control by major record labels, arena-centric presenters and the US commercial-radio cartel. Imagine something comparably liberating in live classical music. (It is already under way in classical recording at boutique and artist-run labels.)

The old star system in classical music, kept on life support by the likes of CAMI, is likely to disappear in the wake of the pandemic. Most orchestras and concert presenters are not going to be in a financial position to shell out six-figure fees to guest artists, even for galas, and most younger artists and ensembles are not going to be wedded to long careers playing the same repertory over and over.

I think we’re going to see a difference in performance scale – again, already under way, thanks to COVID-19: More chamber and chamber-orchestra music presented in smaller and non-standard venues, less fixation on 1780-to-1930 repertory, and more interactive concert presentation. Artists had better bone up on public speaking; conductors had better hone their skills (if any) at reducing orchestral scores to piano.

It’s going to be a different world. That’s not a bad thing.

Anyone remember the “Tchaikovski St. Petersburg Symphony” debacle a few years ago?

It was sponsored by CAMI.

It was not unique.

https://www.nytimes.com/2011/05/17/arts/music/some-foreign-orchestras-offer-misleading-credentials.html

Was that an aberration, or, in retrospect, writing on the wall?