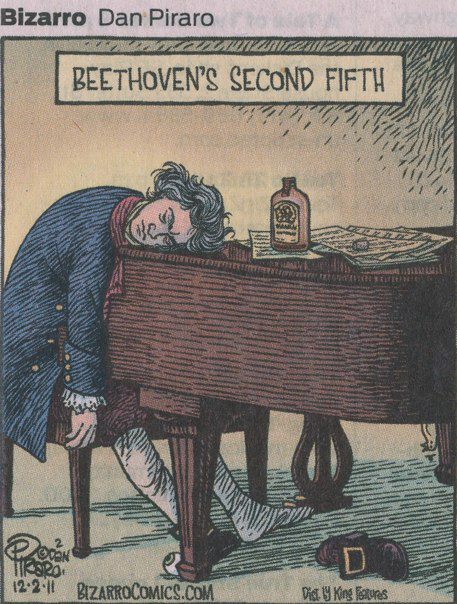

Was Beethoven drunk?

mainWelcome to the 69th work in the Slipped Disc/Idagio Beethoven Edition

Piano sonata no 21, Waldstein, opus 53 (1805)

If you want to think like Beethoven, eat like him.

Given his general lack of order and personal hygiene, it comes as a surprise to find that his diet was quite healthy. The woods around Vienna were rich in mushrooms and berries, the fields in root vegetables. There was asparagus in season and fish was fresh from the Danube. Beethoven was said to be partial to pollock and pike-perch. On the whole, he preferred fish to meat, though he usually had a stew on the go and he kept a salami in the larder. He was not a tidy eater.

For carbohydrates, he liked pasta, preferably macaroni. A legend flourished that he liked macaroni cheese.

If so, it would have been Italian parmesan.

On Thursdays, he ordered bread soup with ten eggs beside it on a plate.

The single most important item in his daily intake was coffee at breakfast, ‘which he usually prepared in a glass machine’. His devoted friend Anton Schindler continues: ‘Coffee seems to have been his most indispensable food, and he prepared it as scrupulously as a Turk. Sixty beans were calculated per cup and he would often count them out, especially when guests were present.’

He liked a glass of wine in the evening at Vienna’s White Swan bar in the Neue Markt. In one letter he writes: ‘Let us meet at seven this evening at the Schwan and drink more of their disgusting red wine.’ There is a theory that lead in cheap wine contributed to his kidney problems. He seemed to have no nostalgia for the astringent whites of his native Rhineland. His father had been an alcoholic, often in trouble with the police, but there is only one report of Beethoven being mistaken for a tramp as he staggered home from the pub, and that account may be apocryphal. Intemperate in so many others ways, he either handled his drink well, or he simply did not drink that much.

Does it matter to our understanding of his works to know what he ate and drank? I think it does. Although he lived in the most appalling squalor and dressed in torn clothes when he could have afforded better, there is an impressive order to his menu. Beethoven ate at fixed times and took regular walks. For all the chaos around him, he understood the creative imperative of good food and exercise.

The Waldstein Sonata – one of his three most popular after the Moonlight – would have been written in this general spirit of wellbeing and dedicated to his friend and patron, Count von Waldstein, who had long declared Beethoven to be the holy spirit in a trinity with Haydn and Mozart. The sonata has also been titled ‘L’aurore’, for ways that it evokes daybreak.

The three movements are, essentially, quick-slow-dance, but all three begin softly. The first known review concludse: ‘The first and last movements are among this master’s most brilliant and original pieces, but they are also full of strange whims and very difficult to perform.’ It lasts 25 minutes and there are almost 200 known recordings of this ever-popular work.

Wilhelm Kempff, a composer in his own right and a veteran of recording studios from the early 1920s, cannot be faulted in this sonata. The absence of any agenda, ideology or affinity in a piece that expresses no more than the joy of being alive allows Kempff to play with limitless freedom and fantasy. I find his 1964 recording to be his most satisfying, a master in command of his craft. All that is lacking is eros.

Vladimir Horowitz, recorded in his New York apartment in 1956, gives the middle movement an unmistakable languour of sex in the afternoon. Impossible to put one’s finger exactly on his G-spot but the eroticism of his interpretation can be almost overwhelming. There is even guilt to be heard between the notes. Who on earth was he seeing? Whoever it was, poor celibate Beethoven would have been envious. Friedrich Gulda (1958) has something similar in mind.

Arthur Schnabel was having a clandestine affair in the 1930s with an American admirer. Something of his seduction technique comes over in the middle movement, which begins as if he is requesting consent, knowing full well that his lover can’t refuse him.

The Scots pianist Frederic Lamond, who recorded in Mach 1930, was one of the last living students of Franz Liszt and therefore a useful clue to the generation immediately after Beethoven. I find his playing pedantic, schoolmasterly, colourless. This cannot have been Liszt’s way.

Benno Moiseiwitsch, a late-romantic specialist from Odessa much admired by the British aristocracy, recorded at Abbey Road in the middle of the Blitz. Emotion is suppressed behind a stiff upper lip, but the range of light and shade is reminiscent of another time and place. Moiseiewitsch studied in Vienna with Theodor Leschetizky. Perhaps he was thinking of a walk in the woods.

The English phenomenon known as Solomon, recording in 1952, treats the finale as an apotheosis, a hymn of redemption from external stresses of war, deprivation and slow reconstruction, one suspects. In all of these pianists, there is more imagination let loose than in the industrial-production recording machines of the 1970s and 1980s.

Emil Gilels (1972) is the great exception. His slow movement is an invitation to something other than intimacy. Gilels seems to be asking us to join him in a quest for nothing less than the meaning of life. He puts the question, then pauses. Puts another, then takes us by the hand. The way he involves a listener in his thought process is, to my ears, unique. Vesa Siren, the Finnish critic on our panel, says: ‘Every time other great pianists start to play Waldstein, for at least a brief moment I wish they were Gilels.’

It’s asking an awful lot of a 21st century pianist to join this exalted company of explorers, but Boris Giltburg (2015), Russian-Israeli winner of the Queen Elisabeth Competition in Brussels, has his own brand of daring and a wonderfully varied set of colours in which to expound it. He is still feeling his way into the literature at this time, but his foundations are secure and his promise high. This is a Beethoven artist who will grow and grow. I am surprised that his contemporary Daniil Trifonov, who often plays the Waldstein in recital, has not recorded it yet.

Clearly there is much more to be said.

Also this is interesting concerning composers and wine:

https://www.futuresymphony.org/composers-and-wine-interview-with-ron-merlino/

For Gilels, don’t overlook the DGG DVD of a 1971 recital in an Austrian church. Not only the Waldstein, but also an Op. 101 of unsurpassed profundity, the Mozart A minor, and a Schumann Nachtstuck Op.23/4 of such subtle, gracious rubato that one wonders why he wasn’t persuaded to record the great Schumann works. The Waldstein’s slow movement here seems warmer and less distant than his contemporaneous studio recording. ( For those with SACD players, Universal Japan just last month released all 9 of the Beethoven sonatas that weren’t recorded digitally by DGG. These appear to be new DSD transfers of the analogue master tapes, and sound far better than what you can hear on the Gilels Beethoven CDs released down the years.)

By today’s standards the camerawork is a trifle stiff, but this turns out to be an advantage for the Beethoven sonatas. ( For me at least, the Barenboim Beethoven piano sonata cycle that EMI released on DVD from Berlin had too many jump cuts from one camera angle to another.)

And the lighting creating a halo around Barenboim’s head was a bit distracting, too. It wasn’t there for his Carnegie Hall cycle.

I have always found Richard Goode’s recording of this among the very best. Some interesting choices to explore here though.

No Maurizio Pollini? His phenomenal recording for DG from the early ‘90s, I believe, is a classic. Pure technical and musical joy. What was he not considered here?

Why (NOT What was he not ……)

Rudolf Serkin.

Thanks for this wonderful story and posting. The history is illuminating and inspiring!

Backhaus?

Bread soup? I liked the parts about his menu; this I didn’t know.

Benno Moiseiwitsch was admired by more than the British aristocracy: he was Rachmaninoff’s favorite pianist (other than the composer himself). He was a great pianist.

I think you missed some of the usual suspects: Richter and Arrau, (one of my all-time favorites), Daniel Barenboim and another South American phenomenon, Nelson Freire.

Richter never played or recorded this sonata

I was a grad student in a physics lab in the late 70’s, and we kept the lab radio tuned to the local classical music station (which was a good one, back in the day). I turned the radio on one morning just as the Waldstein was beginning, and the performance had me transfixed — motionless — straight through to the end (by which time my colleagues and professor had arrived and had to make detours around me). At the end, the announcement came as no surprise to me: the pianist was Emil Gilels.

I do wonder why Beethoven allowed himself to be convinced to replace his original slow movement, the Andante favori. Funny how, for such a strong-willed man, he let himself be persuaded in this instance and in the case of the Grosse Fuge.

Peter — You mention “Andante favori” and “Grosse Fuge” together. Interestingly, the rapid notes at the end of the former are a simplified schematic of their more intense, insistent, and frenetic appearance at the close of the latter. Physics, eh? That could explain a lot. You were very fortuunate in your musical family. Hungarian?

Native Californian, of Hungarian parentage. I try to keep my arts chauvinism in check, though imperfectly.

Your observation, musically connecting the andante and the fugue, is intriguing and will send me to a direct comparison of the two works!

What is this rubbish?

Hello! Other hypotheses point out that the fish from the Danube River that he ate was highly contaminated with lead. Now, if you add the “cheap wine” that others refer to, lead poisoning is assured. Poor Ludwig!

Don’t forget D.BArenboim in his tv recital.

My two personal greats in my favorite Beethoven sonata: Gieseking and Schnabel, both from the ancient 78RPM era. Gieseking is masterful in the first movement, while no one has equaled Schnabel in the final movement, where he makes mighty waves crash against the cliffs.

Close runners-up: Gilels and Craig Sheppard.

I must disagree with you, Norman, in your estimate of Frederic Lamond. I find his playing fascinating. Let us not forget that not only was he one of the last surviving students of Liszt, he was one of Liszt’s last students altogether, this at a time when Liszt was old and preoccupied with many other issues in his life and not the teacher he once was. As you said, Lamond’s playing is no way necessarily a reflection of the way Liszt might have played Beethoven; Lamond was his own man.

And he was an excellent Beethovenist – Lamond was slated to be the first pianist to record all the Beethoven sonatas, but someone (perhaps Gaisberg? Legge?) felt Schnabel’s technique was more up to the task and gave AS the gig.

Greg Bottini — In his contract with HMV, Artur Schnabel stiipulated that if he did not live to complete the Beethoven sonata cycle, Edwin Fischer should be sked to finish it. Not Backhaus, Gieseking, Kempff, or Elly Ney, but Edwin Fischer.

I also like Walter Gieseking very much in the “Waldstein”, and mentioned him before I read your post. Interesting that it’s your favorite Beethoven sonata.

Good coments on Frederic Lamond, who with Mark Hamburg, Emil von Sauer, Felix von Weingartner, and Moriz Rosenthal were indeed among Liszt’s last students, and recorded for HMV and others.

Hi Edgar,

I Hope all’s well with you!

Thank you muchly for the additional info re: Schnabel. It’s very interesting to me that AS should want Fischer to finish for him if he wasn’t able to complete the set.

Lamond’s Beethoven recordings are, as I mentioned, fascinating and quite enjoyable, as are his recordings of Liszt works. He is (undeservedly) nearly forgotten today, but all his solo electrical Liszt and Beethoven recordings are presumably still available in good transfers on a 3CD APR set.

I’m sure you’re aware of von Sauer’s recording of the two Liszt concertos with Weingartner. They are the only recorded examples of Liszt students performing together, and are presumably available on an Opus Kura CD, which I haven’t heard (I own the old Dutton issue, which is superb).

I have heard Charles Rosen play Beethoven sonata recitals on two occasions. His interpretations were overwhelming. As he was a student of Rosenthal, I pat myself on the back for having heard in person a student of a Liszt student!

But I’m not fooling myself into thinking that Rosen’s interpretations are necessarily anything like Liszt’s were.

I’m not sure why the Waldstein is my favorite LvB sonata; it has been since junior college days, when I first heard the Schnabel recording. I didn’t catch up with the Gieseking until much later.

BTW, have you been able to track down any of Craig Sheppard’s Beethoven?

Mark Hambourg won a Liszt scholarship but was never a pupil.

What’s the basis for this? I have always read that Schnabel named Kempff as his preferred successor (as suggested also in the Wikipedia entry on WK).

Fine survey- I would add several more recordings: Among Barenboim’s three recording, the last one, (Decca CD or EMI on DVD ) is exceptionally fine, among the highlights of this cycle.

Arrau is also at his very best in this sonata.

Among 21st century recordings I would add Igor Levit for a very fine second movement.

My all time favorite is – I agree with Norman- is Gilels’ magnificant interpretation.

Alfred Brendel (1974), of course.

For those willing to look beyond the obvious names, there’s a very fine recording by Paul Jacobs on Arbiter. Jacobs understands the kinetic, motoric element of the opening movement, which anticipates Prokofiev. And he plays the octave glissandi in the finale as written.

A very fine pianist. I like this moving tribute to him which ought to have a few more views: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=96ORKky-IZo

“Vladimir Horowitz … gives the middle movement an unmistakable languour of sex in the afternoon.”

Well, it wasn’t with Wanda.

“Impossible to put one’s finger exactly on his G-spot…”

It’d be a medical miracle if you could locate one in a man, unless you’re making a bold new anatomico-biographical revelation about the pianist.

Ever hear of the prostate?

It’s Moiseiwitsch for me in the “Waldstein”, which I saw him play at his Dallas recital in 1955.– deep beautiful tone in the slow interval that introduces the almost Impressionist finale.

This interval replaced the “Waldstein”‘s original slow movement, published separately as “Andante favori” and also recorded by Moisewitsch.

Gieseking, Schnabel, Kempff, Moiseiwitsch’s good friend Solomon Cutner, and Paul Lewis among others.

A couple of years ago I heard Martin Roscoe perform the Waldstein, turning on its head a sonata I thought I knew reasonably well. The first movement (as well as the interlude) changed from a main feature to a slowly building prelude to the last movement when all hell let loose. In the audience it was something I hallucinated rather than heard. Perhaps the nearest equivalent would be the finale of Op 111.

Totally different and utterly compelling. Unfortunately in recording he doesn’t seem as inspired as performance.

“On the whole, he preferred fish to meat…”

He did have the occasional craving for meat. Here is an interesting letter by Schlesinger:

http://uk.apropos.info/beethoven/beethoven_veal/

There are enough references to his drinking habits to assume that he would probably be regarded as an alcoholic by today’s standards.

A fascinating read. The physiological aspects of music is often overlooked until one arrives at the concert hall with a bad stomach …

Can the Brendel and Schiff recordings of the Waldstein also set high standards in this sonata?