No work of Beethoven’s is easier to play badly

mainWelcome to the 57th work in the Slipped Disc/Idagio Beethoven Edition

Piano Sonata No 14 in C sharp minor op. 27/2 “Moonlight Sonata”

Beethoven’s second sonata under the opus 27 number bears the same title as the first: ‘Sonata quasi una fantasia’. The 14th sonata did not acquire the Moonlight title until a few years after Beethoven’s death when the poet Ludwig Rellstab said that’s what he was reminded of in the opening melody, the moon shining on Lake Lucerne.

The title stuck like chewing-gum to a shoe-sole and could never be removed. It has also featured as the title of a novel, a film, several documentary works, numerous paintings and as the origin of a Beatles’ song ‘Because’, yet that does not explain the enduring popularity of the original music. What gives the Moonlight Sonata its unique place in millions of hearts is the opening melody, which is so simple that that a child or an adult beginner can play it with perfect accuracy after no more than three or four piano lessons.

‘Surely I must have written better things,’ sighed Beethoven when the first royalties rolled in. Contradicting himself, on another occasion he told the piano specialist Carl Czerny that, together with the Appassionata, this was his favourite piano work.

There are 189 different recordings on Idagio and you’d go mad if you listened to more than a tenth of them. No work of Beethoven’s is easier to play badly, and none has been played worse by some of the greatest pianists on record. The hypersensitive Vladimir Horowitz, for instance, performed few of the Beethoven sonatas, choosing the three most popular when he did. He recorded the Moonlight Sonata three times. The first, at Town Hall New York in 1947, is barely listenable in distant, crackly sound. The third, taken in 1973 is aloof to the point of disinterest. The second, taped in his own living room in 1956, has certain unique qualities, such as record speeds in the finale and bizarre twists and turns, which persuade some critics to number it among the great Beethoven redorcirngs. What I miss is the unique timbre that Horowitz brings to every other composer he approaches. He just doesn’t have it in Beethoven.

Infinitely more interesting is the Russian pedagogue Heinrich Neuhaus (1888-1964). A pupil of Scriabin (he made his Moscow debut playing all 10 Scriabin sonatas), he was the teacher of Richter and Gilels and a close friend of Pasternak, who ran off with his first wife. Neuhaus is a Russian cultural monument. When he plays the Moonlight Sonata it does not splash light on a Swiss lake so much as conjure a cloistered contemplation of human dliemms, dreams and disasters. The sound is remarkably clean for Soviet standards and the playing unforgettable. Its antithesis is Maria Yudina, who denies the possibility of pleasure, as if morally deterred by the work’s popularity.

Evgeny Kissin, a pianist who is often likened to Horowitz, creates his own timeworld in Moonlight, and very persuasive it is. Like a university philosopher, Kissin has a way of throwing a bridge of an idea across a sea of ceaseless detail. He keeps the listener’s mind on the main theme as intently in the static opening movement as in the frenetic finale. Some find Kissin a tad detached; in this sonata he is all there.

Lang Lang has not recorded this sonata, at least not yet. His arch-rival Yundi Li, winner of the 2000 Chopin Competition, made a 2012 recording for DG which is exaggerated in both speeds and dynamics and was a great success among his teenaged groupies. Valentina Lisitsa, a Ukrainian with a huge Youtube following, lets herself down with muddy chords in the finale.

Rudolf Serkin occupies a position in American piano playing analagous to Neuhaus’s in Russia. As a teacher at the Curtis Institute and co-founder of the Marlboro Music School and Festival, he mentored three generations of US pianists in a non-intrusive way, cultivating varieties of personality and inclination in his studio. Never a flashy pianist himself, drawn to the drier and more thoughtful composers, he plays the Moonlight as a demonstration piece, his analysis almost audible as he plays. His mind runs twice as fast as his fingers. For comparison, go to the Swiss master Edwin Fischer (1949), who seems to turn inwards where Serkin looks out, yielding nothing to curiosity seekers.

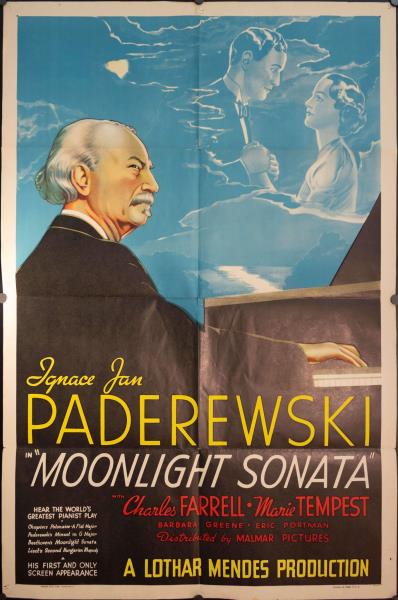

No discussion of the Moonlight Sonata would be complete without taking in the dramatic role of Ignacy Jan Paderewski, formidable virtuoso and, from 1919, first prime minister of independent Poland. Paderewski first recorded the Moonlight in 1906 at a stubbornly deliberate plod when the engineers must have been urging him to speed up as the shellac was running out. He did, just in time. Twenty years later he recorded it again, in New York, wiser and faster. The third recording, and the most famous is the one he made in 1937 for the movie Moonlight Sonata, in which he co-starred opposite Marie Tempest and Charles Farrell.

The story? Young man tries to win the hand of rich girl. A plane with Paderewski on board makes an emergency landing in a field nearby. Turns out Paderewski’s playing brought the girl’s parents together 20 years earlier. Curtains, all live happily ever after. You can hear why people fell in love to Paderewski’s playing: it’s hypnotic.

The great man died three years later in New York, aged 80. His remains were returned to Poland in 1992.

Comments