When Celi was chief of the Berlin Philharmonic…

main… between the end of the War and Furtwängler’s return.

… between the end of the War and Furtwängler’s return.

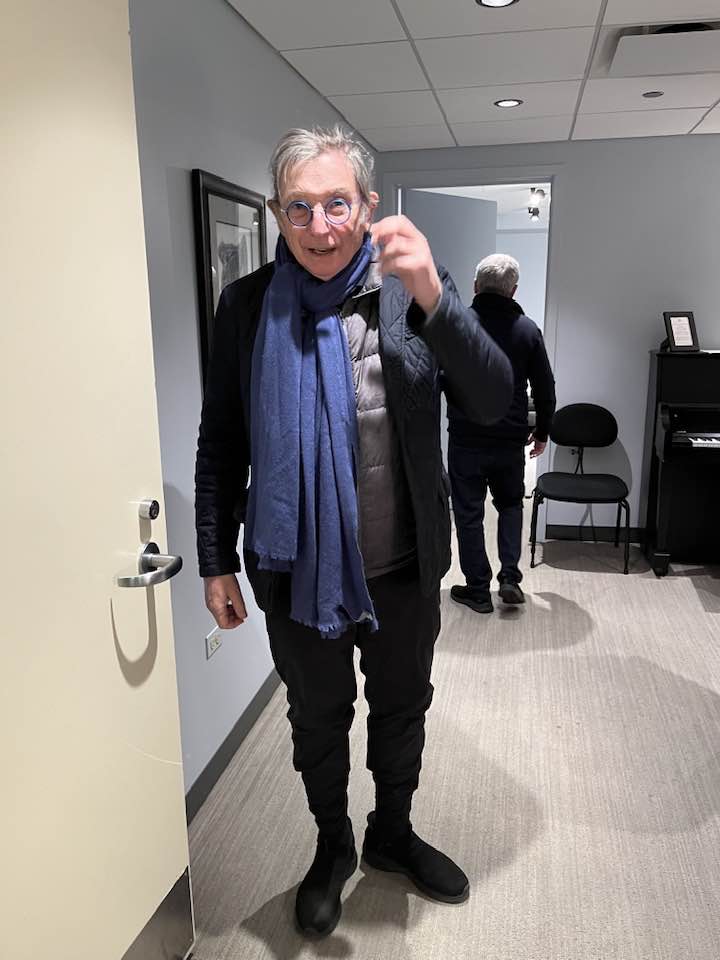

We hear that Stephen Rose, former head of…

There have been some irreparable losses. Germany mourned…

The steady departure of cherished professors at the…

The prolific international conductor Michael Tilson Thomas, diagnosed…

Session expired

Please log in again. The login page will open in a new tab. After logging in you can close it and return to this page.

…the Berliner Philharmoniker, in a gesture of cultural surrender to the victorious Americans, for the first time ever used American seating, Celli on the right outside. Fortunately that was only a short lived fashion. After Furtwängler’s return the strings were going back to the acoustically more reasonable seating in the middle again.

Celi though, in contradiction to his own keen interest and perfectionism all things acoustical around music, used the misguided American seating all his life.

Tonmeister: “Celi though, in contradiction to his own keen interest and perfectionism all things acoustical around music, used the misguided American seating all his life.”

Yes, poor thing, it’s a shame he didn’t have your far more gifted ears to guide him…and what rubbish the results above!

(Forgive the sarcasm, learned friend – just couldn’t resist needling your pompous certitude.)

Dear angry friend, if you believe anybody with fame is immune to ignorance and therefor must have the position of ultimate certitude in all matters, then you speak with certitude in promotion of servitude.

And above results are presented in a mono recording, rendering the seating almost irrelevant to the results, certainly.

“Angry”? Oh, dear…defensive AND tone-deaf.

Okay! This is a no brainer! In a live concert it’s better when cellists sit in the middle because the F holes are facing the audience. In a recording it doesn’t matter where the cellos are because they have microphones. When the cellists sit on the right in a live concert, because the F holes are turned toward the back of the orchestra, it can happen that the middle register tones are lost or not strong enough. That’s it!

Misguided? How? There is no perfect orchestral seating plan. No best, either. Many conductors have experimented with seating and there’s no definitive plan. Think Stokowski. Some conductors change it depending on what the music is or what the hall is like. I like violins split left/right. But then you get a score like the Shostakovich 5th with 3 violin parts and you have a new problem. Maybe the reason so many American orchestras play with such brilliance and ensemble is that misguided seating.

For pretty much all repertoire up to the early 20th century the traditional seating with violins split left/right and the celli playing frontally into the audience is clearly the best. It’s also visible in the scores, that composers expected that seating.

Few exceptions apply under special acoustical circumstances.

Stokowski, well… Just because he experimented with it, doesn’t mean it justifies changing the seating.

After Bartok, Stravinsky, Shostakovich etc. I agree, it’s more flexible, how the string seating should be.

Brilliance: you make it sound like there can never be enough brilliance. But that’s not what the music most of the time requires. IMO many top American orchestras have an overly brilliant, borderline harsh industrial sound ideal.

And ensemble is not depending on American seating. In fact having better contact between top and bottom voices, having the basses behind the first violins as in the traditional seating, often improves the ensemble and intonation.

…also note that many American orchestras today have gotten the news and have gone back to a pre-Stokowski seating by default (while being more or less flexible for other seatings at times for particular programs or conductors).

NY Phil: Furtwängler variation. Violas on the right

MET: (un-American) traditional seating

LA Phil: recently apparently made the switch to traditional seating.

Pittsburgh: traditional

Cleveland: Furtwängler variation. Violas right

Dallas: dito

etc.

Who decides the seating? Orchestra or conductor? On more than one occasion, on both sides of the Atlantic, I’ve seen orchestras change seating arrangements depending on the conductor, even on a guest conductor. I’ve even heard private comments of exasperated musicians being unable to hear each other because of a seating the conductor imposed.

AFAIK most orchestras have a default seating, and on top of that some conductors with a good relationship with the orchestra can chose their preferred seating, if they see a good reason for it.

Chief conductors sometimes change the default seating.

Musicians complaining about a change in the routine? No, that can’t be. Never heard about such a thing. 😉

On a related note, if I recall correctly, Herbert Blomstedt once talked about seating arrangements, stating that the Staatskapelle Dresden and the Gewandhausorchester Leipzig had specific clauses in guest-conductor-contracts, requiring the invited conductor to acknowledge and abide by the orchestras traditional seating arrangement (exceptions only being granted with the explicit consent of the musicians themselves).

On an aside, does anybody know the reason for the Concertgebouw Orchestra placing their bassoons behind the flutes and their clarinets behind the oboes, an opposite seating from that employed by virtually all other orchestras?

Easy to resolve, the old blind test thing. Place a select audience in a hall. Orchestra not on stage. Audience puts on blind folds. Orchestra takes seats plays a number selected to be neither too short nor too long. Orchestra leaves stage.

Audience takes a break and fills out survey on what they heard.

Repeat the process. Orchestra changes seating or keeps from first time. Do over a period of several days.

I’d be willing to wager that the largest number of audience members won’t be tell the difference.

Oh well, with that test you could wager, that the largest number of the audience won’t be able to tell the difference between Florence Foster Jenkins and Anna Netrebko.

Or between a metronome or Riccardo Muti conducting. etc.

I base my observation on a quasi-scientific test conducted at a meeting of the International Horn Society several years ago. The gentleman who conducted the test, his name slips my mind, arranged for several well known players to play four different top line horns. They did this behind a screen. The purpose of this test was to determine if the audience could determine horn make by sound alone. As the test progressed audience members said they could recognize the players but not a real difference in the music produced. The kicker was horn #1 and horn #4 were the same instrument.

There is a lot of “I know I could tell the difference” out there. There is nothing to validate this claim.

I believe anyone who actually uses their ears will be able to distinguish whether the cellos are on the right hand side or somewhere in the middle of the ensemble without much difficulty. Same with the basses. The sad thing is that I reckon most audience members do not really know how to listen – actively to listen, that is. Most are basically passive listeners.

Singling out a make of horn, though, is quite different and a much more complex and difficult process. I honestly do not believe you can equate that with the positioning of sections within an orchestra on stage.

If you sit in the expensive seats, in front of the orchestra, relatively close to the orchestra you can indeed hear the placement. When orchestras split the violins left and right it makes a startling impression listening to things like the finale of the Tchaikovsky 6th, most any symphony of Brahms and Mahler. But as you go back in the hall, the stereo spread diminishes significantly and all the sound seems to emanate from a single point – kind of like a mono recording. You still have the reflected ambient sound in a good hall, but positioning a section by sound becomes quite difficult, except maybe for the low brass.

Maybe a listener can’t tell the difference in horn makes, but the players sure can. A horn that fits a player well is flexible, has just enough resistance, and can play at all volume levels. Cheaper horns are much harder to play than more expensive ones. Same with almost any wind instrument. An expensive $50,000 Heckel bassoon may not sound any different than a $10,000 one to listeners, but ask any player which is easier to work with.

The horn example is turning into a “Squirrel” so I injected it. Though the thing about good horn players they can sound good on almost any make of horn. It what they’ve learned to do.

If you call one seating “traditional” and “clearly the best” and “visible in the scores” it makes it sound like that is, indeed, the better arrangement, but those are just claims.

I actually *asked* Celibidache why he used the seating he did. It had nothing to do with Americans (who were not the ones to introduce this seating, by the way). This is why Celibidache seated the orchestra the way he did, according to the master himself:

======

There is an order from high to low pitch that goes from left to right. It’s not just in the strings, but in the brass and winds, too. As in a choir, the strings have soprano (vn 1), alto (vn 2), tenor (va) and bass (celli/bass). [Celibidache arranged the choir the same way.]

The brass is arranged in the same pitch order, with trumpets on the left, then horns, then low brass.

====

In fact, Celibidache put the horns as close to the violas as he could. Why? because they often share harmonic functions and range. For the same reason, low brass and cello/bass should be near each other. Sometimes the horns were in the winds, to the right of the oboes (behind the violas, as if they were last-stand violas).

He agreed with Stokowski that there should be a clear pitch continuum, spatially, across the entire orchestra and that like-functioning instruments should be near each other, if possible. There are several spots in 19th-century scores that suggest this is a logical arrangement. For example, the first movement of Beethoven’s 7th, Tchaik 4, just to name a couple. In those works a figure is passed from high to low and back up again. In a live performance, the motive “moves” across the stage and back. Nevertheless, the spatial location of motivic elements in western music is of minimal importance (relative to other modes of musical organization and function).

It’s not at all certain that just because 18th century seating was the way that it was, that that was the seating composers of the time thought would be best for playing their music. After all, spatial location takes a (far) back seat to harmony, line, and rhythm when it comes to musical parameters that composers felt were important enough to notate.

Do you know of any contemporaneous composers’ explanations for a particular seating, or critique of one, or preference for one? It would be interesting to hear if they cared, and if so, why.

Since we (people) have almost no ability to spatially locate bass frequencies, there is almost no reason to put the bass instruments in the middle. The lower they play, the more non-localizable their sound will be. Therefore, you can understand an argument that it makes sense to NOT interrupt the grouping of higher frequency instruments with a bunch of cello and bass players (because their location makes little acoustic difference).

Stokowski’s (and Celibidache’s) way is one way of looking at it. It has logic, acoustic phenomena behind it, and it works (does not thwart great music-making). You can assess whether it (the seating) does what its supposed to do. Whereas, if it’s value is tied to whether it’s “traditional” or “American,” then there is no musical way to assess whether to use it or not (and it’s just a matter of preference.)

It occurs to me that I have never seen choirs with SBTA seating. That would be the equivalent arrangement to VN, VC/CB, VA, VN2. Given that choral voice parts have (in many pieces) the same functions as their string counterparts, I wonder why we don’t see that.

Incidentally, in the Gasteig hall in Munich, Celibidache was exceedingly perplexed with the problem of the bass sound. He was constantly tinkering with placement of the ENTIRE orchestra farther to the left or closer to the front of the stage, etc., in an attempt to reduce the prominence of low frequencies. I’m not sure he ever felt he got it “right,” but it never was a question of doing what American orchestras did. I would be surprised if that had had anything to do with why Celibidache chose the seating he did.

But Celibidache’s idea, that the seating must reflect the pitch of the instruments in linear fashion is arbitrary and has no justification in the phenomenology of sound. Celi was simply wrong on that.

To the contrary, it is better to separate neighboring voices laterally in space, since then they are easier to differentiate for the listener.

You are also wrong on the ‘bass instruments’ as you call them. There is a confusion in your argument between harmonic function (bass voice) and acoustic phenomenology.

A cello and even a bass are *acoustically* not limited to the bass register.

They are full spectrum instruments. To hear their line, their harmonic function, their rhythmical ‘gestalt’ well, they should be seated in a way where the full spectrum of their sound energy reaches the majority of the audience.

Celli in particular are prone to being very directional in the radiation of their sound, due to their position in front of the body of the player mostly.

If you ever sat behind the stage in one of these surround concert halls and heard a cello concerto, you would know. Contrary to a violin concerto, which behind the stage sounds a bit dull for the solo voice but you can still hear the violin somewhat, for a cello you almost completely lose the sound behind the player behind the stage. The effect starts on the sides already.

Which is the reason why – as any experiment with the seating will show – the celli should sit in a way to the audience, where the instruments face them frontally and show the biggest surface, which gives the most sound energy over the full spectrum to the audience.

Arguably also in much of the classical repertoire, a bass voice (harmonic function) that is rich in energy and has contour of the ear to follow it better (overtones, transients and bowing noise give that) is beneficial for the ensemble and the listener alike, it improves the ability of all other instruments to base their voice in intonation and rhythmical (Celi would have said ‘vertical’) context. Which is one reason why in Vienna the double basses form a row behind the orchestra. As a fundament to all. The other reason they are in front of the wall is the nature of nondirectional radiation of bass energy, which means sitting immediately in front of a (large) wall, their bass sound energy is amplified.

A conductor who is exceptionally egocentric (hear hear) might not care so much where the celli sit, since if they sit frontally to the audience or sidewards, they always sit frontally to him, he hears no difference…

The same can be said about the early days of mono recordings, with one microphone approximately above the conductor’s head. Maybe it is not a coincidence, that Stokowski enforced the concept of a string seating linear high to low voices, because it was the most efficient for mono recordings.

Again, to say proximity in pitch of voice dictates proximity between groups is not a valid argument. Many traditional seatings (Wiener Philharmoniker) show a clear preference to base the harmonic architecture on the bass lines. Which requires their positioning to be beneficial for listening for both the rest of the orchestra and for the audience alike.

To place the basses close to the first violins is beneficial for defining the outer voices of the harmonic structure in intonation.

Many choirs on semi-professional level and better these days also experiment with a mixed placement of singers, no groups, but individual alteration, so each singer is immediately neighbor to all other voices. That gives the maximum connection in the harmonic and rhythmical context, but requires good ability to hold one’s own line nevertheless. I have also seen SBTA or other choir seatings that do not follow the SATB linear fashion very often.

We find examples for a seating with Celli in the middle (frontally to the audience and violins split left right) in an overwhelming amount of scores. From Mozart to Bruckner and Strauss. It was simply the standard and the composers knew it and used it also for lateral spatial effects.

To place instruments with harmonic neighboring voices or even unisono playing at times close to each other has only *one* reason: efficiency. It is arguably easier for the first and second violins to play in unisono, if sitting next to each other.

But if you once heard a climax in a big orchestration by Mahler, Bruckner or Strauss with the violins distributed all over the front of the orchestra in the biggest possible width, you will be sold to that sound which gives the best of all worlds, full bass, full tone and brilliance, and lateral separation of the voices that makes it easier for the listener to enjoy the polyphony and harmonic richness.

After all, psychoacoustically our ears prefer neighboring harmonic voices with lateral separation, not proximity, since that eases the process of dissecting the voices in their individual lines again at will, enjoying the polyphonic richness much more.

A master’s thesis on orchestral seating:

http://www.jdsmusic.co.uk/Orchestral%20Seating%20-%20JDS%202009.pdf

SC was selected by the Americans to lead the Berliners during this period of

de-nazification.” Does anyone honestly think that the American Army dictated the seating arrangement? Celibidache insisted on this seating ( 1st, 2nd, viola, cello from conductors left to right) in 1984 at Curtis and, believe me, he could have had any configuration he wished. Many of the videos of SC with various orchestras also show this arrangement.

This video of Egmont was an obvious propaganda tool (note the sun breaking through the clouds at the coda) “orchestrated” by the Allies, especially the Americans. The performances is, IMHO, rather theatrical but effective…very different from the tempi SC chose toward the end of his career.

For better or for worse, like it or lump it, it’s a historical document of interest both politically and musically.

“Does anyone honestly think that the American Army dictated the seating arrangement?”

We don’t know, but it is a curious correlation, that this propaganda film by the Americans is the very first time the Berliner Philharmoniker string section is documented to be sitting in the ‘American’ fashion. All the war time footage (Furtwängler Beethoven 9 etc.) shows a traditional seating.

Since the bizarre way Celi as a conducting graduate of Berlin music academy became right away the acting chief conductor of Berlin Phil after the war must have left great primal imprints on him, this seating might then become his preferred one, nevertheless his interest in all things acoustical should have told him later, that it is a mediocre solution only.

Since Furtwängler on his return showed much of a cold shoulder to the young competitor, we can also speculate, that this seating was somewhat of his ‘mark’, to separate the young lion from the old lion. All speculation…

One forgets that orchestras in the 18th and 19th centuries were mainly opera orchestras and the setting in the orchestra pit should be quite different due to the reduced space therefore the basses on the back side and celli in the middle since bowing horizontally a cello placed on the right side of the pit would be a problem by hitting the wall. By consequence when moving up on the stage in order to play a symphonic repertoire the orchestras kept their usual setting. I wonder whether the violinists in the second violin section and the violists are really happy struggling to project the sound when their instruments are facing the audience with the back.

Sure, and brass players sit in the back, because in the opera pit they need to be able to sneak out into the canteen for a beer during their long rest periods…

Not so. Acoustical laws are the way they are.

Just listen.

Or get a good book about the subject that explains it in detail.

https://www.amazon.de/Akustik-musikalische-Aufführungspraxis-Jürgen-Meyer/dp/3955120589

The loss for the second violins or the violas on the right is less, since their instruments are not in the acoustical shadow of their whole body, as the celli are.

I am a cellist and I played often in string trio and string quartet and I know how reluctant the violists are to sit on the right side. This is the reality from inside and it reflects the musicians’ preference no matter what the books say. Orchestra musicians follow the required adjustments coming from conductors or managers. By the way in the La Scala’s pit the brass is located on the right side though quite far away from the door and the corridor leading to the alcohol as you, Tonmeister, would imagine.

Abbie Conant.

I like how skillfully Celi conducts with his hair.

First, I would like to thank all who are taking the time to discuss this topic. I’m learning a lot from you!

I have a couple more observations to make after reading and thinking more about the points raised here.

It seems we will never determine which seating arrangement is “the best one.” That’s because there are differing ideas about what “best” means. And there are so many differing conditions (variables) that render one arrangement “best” in one case and “worst” in another.

In light of this, I’m gravitating toward three criteria for judging the value of any particular seating arrangement:

!. Does it help or hinder the musical results?

I think we all can agree that the proof of the pudding is in the eating. Or hearing. But hearing pudding is just gross. To call any particular arrangement “mediocre” when it was the plan used during a concert-of-a-lifetime, would be to utterly miss the point. Whether the artistic result was “because of” or “in spite of” the seating is most likely unknowable. However, if great performances are not forthcoming, changing the seating might help!

2. Does it empower or piss off the musicians?

The instruments of the orchestra are not mindless tone-generators at the service of a conductor-cum-audio-engineer. The person playing the instrument has ears and a brain, and they will make all sorts of conscious and unconscious adjustments to play the music, no matter what position they are placed in.

I would rather choose whatever arrangement those particular musicians prefer or are used to, than risk annoying them because of some exceedingly small possibility that the clarity and intelligibility of their playing, or their intonation, might be thwarted by their placement. You can lose musicians’ respect almost instantly by insinuating anything of the sort. Such loss of respect would likely have a larger impact on the musical result than the minor acoustic adjustments afforded by this or that seating arrangement.

3. Does the physical space require spatial adjustments?

For example, cello bows not hitting the wall in an orchestra pit is probably more important than maintaining a high-low frequency spatial distribution.

“Ac-cent-uate the Vertical”

One thing we haven’t discussed here yet is vertical space. When I was in orchestra at the back of the cello section, I was astounded when we began using risers. This was like “stadium seating” that you find in some movie theaters – and the impact was instant and obvious. Because each of us could hear the rest of the group with something like the vantage point of the conductor, we could far better fit into the ensemble (in many more ways than just balance).

Choirs use risers very, very frequently (predominantly). I wholeheartedly recommend them. And if you think they’re bad because they might make the brass too loud, think again. When brass players (or anyone else) can hear clearly, they can balance themselves much better, without having to rely on conductor signals, or their own estimations from a “blocked” position. Trusting the musicians while at the same time giving them more and better information (i.e., a better ability to hear everyone else) is a winning strategy.

Maybe we don’t see much more use of risers is their cost (of setting up/tearing down) and not their lack of positive impact on musical quality.

o o o

In general, then, I think seating arrangements ought to flow primarily from what musicians best need to be able to do the job, and secondarily what limitations the space may be imposing.

This is probably obvious, but I would treat adjusting the seating arrangement as a last-resort musical tool. In other words, if the musical “problems” we’re having can’t be solved by listening and playing, AND a seating change might help solve those specific problems, then (and only then) are spatial positioning changes worth trying.

Now you’ve done it. Another element: risers SC demanded risers and in Carnegie it cost a fortune (stagehands union, et al). and the last row had to be 2 meters high (that’s about 80 inches or 6 feet 8 inches. He also demanded a circle of clear space between the podium and the first desks of strings of 2 meters so that he could get a true perspective on the sound mix. (Honestly, we cheated on both; the top riser in Carnegie was lower than demanded and the space around the podium was about 1 meter.

Speaking of risers and seating arrangements:

https://www.google.fr/imgres?imgurl=https%3A%2F%2Fclassicalvoiceamerica.org%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2015%2F09%2FPhilly-Stokie-595.jpg&imgrefurl=https%3A%2F%2Fclassicalvoiceamerica.org%2F2015%2F09%2F30%2Fthe-philadelphia-orchestra-sound%2F&docid=PeOdq8MPxAWmQM&tbnid=4K-Sc7TGwywENM%3A&vet=10ahUKEwiwoLeqsqbbAhWRy6QKHUoeBRgQMwg6KAIwAg..i&w=595&h=374&bih=602&biw=1242&q=stokowski%20orchestra%20seating&ved=0ahUKEwiwoLeqsqbbAhWRy6QKHUoeBRgQMwg6KAIwAg&iact=mrc&uact=8

I do read with a bit of bemusement the statements that show a certain disdain for US actions after WWII. It was a European mess we really didn’t want a part of. Twice in the last century the US got sucked into those conflicts. I know one European musician who complained about towns in Germany and Austria being “shot up” by forces of the American 3rd Army. He said there was no resistance in those towns. The 3rd Army Commander had in fact order his soldiers to leave indelible marks on these here to fore undamaged towns as “American War Memorials.” Just a reminder of what they had started.

1. why did he nver conduct opera?

2. what was his stand during the nazi era?

In brief (I am sure there are many here with more knowledge on SC who can expand or explain better)…

1. (From a 1984 NYT article) “And his experience with opera is minimal; he did a few in Berlin, with unhappy results. He did not say so in as many words, but the implication was that the trouble with opera is singers.

”You have to have very bad ears to be an opera conductor,” Mr. Celibidache said.”

2. Read here: http://www.fundatia-celibidache.com/biography