Alastair Macaulay: ROH choreographer isn’t without talent

balletOur dance critic has seen the dark side of the Royal Ballet’s Festival of New Choreography:

by Alastair Macaulay

In repertory at the Linbury Studio Theatre until February 20.

The word “festival” suggests a celebration. This month, the Royal Ballet is presenting a Festival of New Choreography this month. Here’s hoping that the festival leaves us seeing serious new possibilities for ballet as an art form. But its opening item, “Dark with Excessive Bright”, isn’t just a (superficially pretty) anthology of clichés – it reminded me how horrid, how dated, and how boring ballet itself can be.

“Dark with Excessive Bright,” the work of the Canadian choreographer Robert Binet, occurs in the Linbury Studio Theatre, lasting forty-five minutes. It’s one memorable device that it stages three simultaneous dances in separate areas of the floor, so that the audience can either watch the whole from an upper balcony or parts at close quarters. This is nothing new: at Tate Modern in 2003, Merce Cunningham (1919-2009) presented an Event on three simultaneous stages, and went on to present subsequent Events on multiple stages for the rest of his career. The difference is that Cunningham’s simultaneous dances were thrillingly unalike and all first-rate.

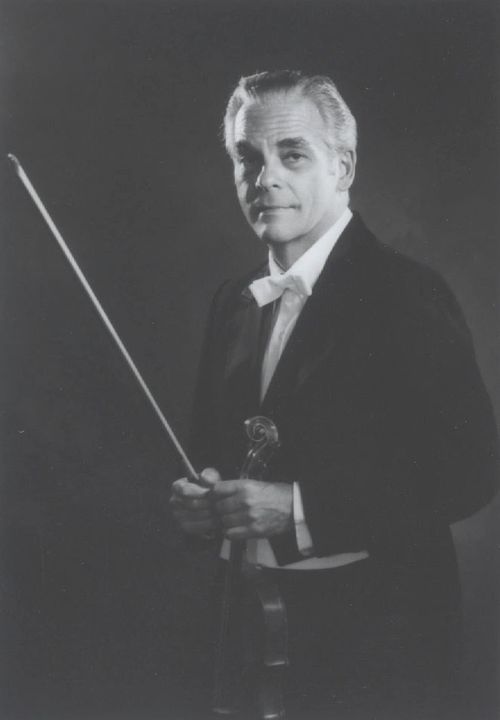

Binet – who has been choreographic associate to the National Ballet of Canada – isn’t without talent: in 2015, his “The Blue of Distance”, for New York City Ballet to Ravel piano pieces, was a changing landscape that often showed speed, slowness, and stillness simultaneously (and musically) on one stage. Here he gives us three stages on which everything is tedious, unoriginal, lethargic, precious, interchangeable, and wretchedly mannered, with many laboured demonstrations of “sensitivity”. The eleven dancers wear body tights in various shades of beige flesh tones; the men’s torsos are also clad in coloured but translucent veils. The music, by Missy Mazzoli, is drearily precious. Some of it is played live by a pianist and (at one point close to the stage) five string players: all of it is about mere surface effects.

Piquée arabesque, the épaulé arm gesture forward into space, the manège of piqué turns, the forward bend from the waist, the small assemblé jump – there’s no harm in showing us these familiar parts of the ballet vocabulary. Binet, however, gives us whole phrases consisting of nothing else. A few dancers – Reece Clarke, Nicol Edmonds, Anna Rose O’Sullivan – delivered their dreary movements with admirable honest-to-goodness simplicity , but too many (even the usually marvellous Joseph Sissens) did them with misguided facial displays of deep feeling.

In particular, it allows people,to see at close quarters how clunky the Royal Ballet’s current point shoes are, with women’s blocked shoes seemingly sawn off to make the foot look not pointed but crudely truncated, as if by hostile carpentry or amputation. (To make matters worse, the edges of the “point” area are now sewn into a frayed look that suggested wood-shavings.) This is not how the shoes of other important ballet companies look; it is antithetical to the elegant illusion that ballet pointwork has been all about.

Heaven knows I have no objections to men lifting other men as well as women. This has become not only a hallmark of twentyfirst-century ballet but one of the few ways in which ballet echoes those western societies in which same-sex relationships are now open. And yet Binet makes it look mere tokenism.

At no point do men and women do the same movements side by side; at no point does the footwork of men and women ever resemble one another. (And isn’t it time we saw male pointwork? With those hewn-galosh pointshoes, Covent Garden is all set to lead the way.) The stage society here never suggests equality in the workplace. The dancers here look like some singular species in the zoo, never like people in the modern world outside.

The only mention of Missy Mazzoli’s music here opines that it is “drearily precious” and “about mere surface effects”. Is this a just criticism? I for one would disagree.

Love me an Alistair Macauley review!

What a dull, irrelevant, and spiteful review. Anyone who enjoys reading such diatribe only shares the same miserable mental inhabitants as the author. Just a sign of the times though. Selling himself out to controversy for the sake of a few clicks. I am only disappointed that I see the need to give this oxygen.