Alastair Macaulay: Is Tosca really a masterpiece?

OperaThe former NY Times chief dance critic reviews last night’s ROH revival of Puccini’s warhorse for Slipped Disc. The more he sees this opera, the more doubts he has.

by Alastair Macaulay

Puccini’s Tosca will be 125 years old next year. Jonathan Kent’s production, new in 2006, returned to Covent Garden repertory on Monday night for a group of five performances with one cast this month. (It will return in July, with two other casts and one other conductor, for eleven more showings.) Puccini’s score is fragmentary, and can be jerky, but American conductor Karen Kamensek – physically tiny – made it cohere skilfully.

She brought particular focus to the three chunks where Puccini is at his most musically and dramatically complex: in Act One, the Te Deum (offstage cannon fire, church organ and congregation, all overlapping with the villainous Baron Scarpia’s erotic and political machinations); in Act Two, the cantata (when Scarpia interrogates his prisoner, the artist Cavaradossi, while religious music – led by Cavaradossi’s lover, the singer Floria Tosca is sung in concert offstage); and in Act Three, the slow march at the Castel Sant’ Angelo (in which soldiers formally enter and prepare to execute Tosca’s lover, the painter Cavaradossi, while she maintains a running commentary about his performance of what she thinks is a make-believe death).

On Monday, it was marvellous to feel how all the separate layers of these scenes registered. Kamensek caught the inexorable pulse of these passages, while keenly realising such internal details as the tiny string portamenti, which lend their own texture and commentary. In such sequences, opera – showing how the public and the private intersect – is poignantly overwhelming and undermining at the same time.

Even so, and even though it’s over fifty years since my first Tosca (in this very opera house), I’m increasingly inclined to resist much about this warhorse. Its many admirers are right to call it a masterpiece. But a masterpiece of what kind? Really Tosca is about manipulative theatricality rather than of seriously convincing drama. It flamboyantly brandishes Christianity in all three acts, but really just for theatrical effect. (None of its invocations of God are as a fraction sound as sincere or touching as Minnie’s Bible reading in Puccini’s own La Fanciulla del West.)

When the determinedly secular Baron Scarpia, in church, calls out, “Tosca, you make me forget God!”, it’s just a standard melodramatic ploy. (It’s derived from Victor Hugo’s “Nôtre-Dame de Paris”, where the far more interestingly conflicted character Frollo genuinely thinks he doesn’t want to be tempted away from Christianity by the helplessly attractive Roma dancer Esmeralda.) As for Tosca’s renowned aria “Vissi d’arte”, it’s a display of religious passive aggression. (“God, I’ve done good things and done charitable deeds, so why do you repay me this way?”) Her belief in God then allows her to commit both murder and suicide.

Religion is just one of the triggers employed in Tosca; art is another. But I’m less moved by – I have less belief in – Cavaradossi’s painting than I do with Marcello’s in Puccini’s La Bohème; and Tosca the singer is more of a harried professional than a dedicated musician. In Kent’s superficially glamorous production, Paul Brown’s designs for each act feel like several separate zones tacked together; Mark Henderson’s lighting is no help here. (And the stars in the night sky above Rome in Act Three are absurdly large.)

All three of Monday’s lead soloists had telling moments. The Lithuanian soprano Ausrine Stundyte was touching in Tosca’s moments of greatest frailty, but under pressure her voice proved both squally and underpowered. The Italian Gabriele Viviani has the authority to carry the role of Scarpia; but his voice, too, tends to lose firmness in the most proclamatory passages. Best was Marcelo Puente as Cavaradossi: although this Argentinian tenor’s voice becomes slightly tight at top and bottom, he often weds words and melody to gorgeous effect. Nothing all evening was more touching than, as Cavaradossi prepared for death, his quiet statement “Io lascio al mondo una persona cara”: I leave to the world one person dear to me. In such lines, Puccini’s understanding of human sentiment still flies to the heart. Manipulative, yes; but here I confess myself successfully manipulated.

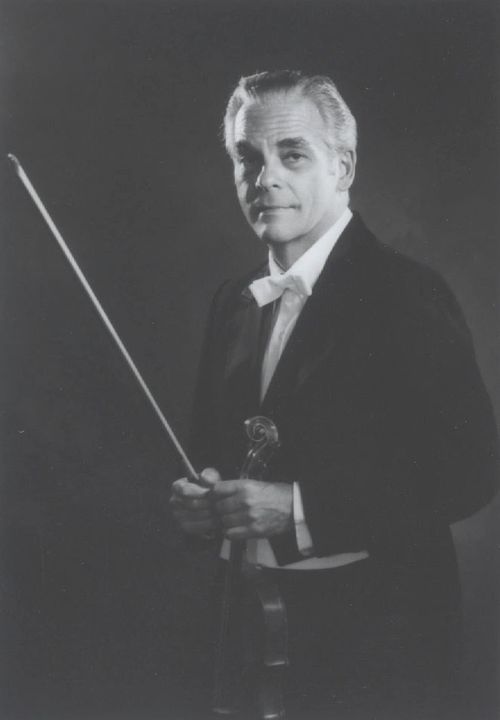

press photo: Marc Brenner/ROH

No, it isn´t..Vulgar,cheap little shocker.Musically tacky,cheesy, and also vulgar.Exactly like the plot. Like a cheap italian thriller from the 1970s.

Under other skies maybe, these vulgarities occur on a daily basis.

Well chacun and all that, however, in my opinion, it’s still more fun, and more enjoyable than all of the newer operas I’ve seen at the Met during Mr. Gelb’s tenure………..

You are on the wrong website. This is a website for classical music.

Oh dear, if he applied the same standards to ballet, “manipulative theatricality”, then no ballet would be a masterpiece. (C`mon, dancers flapping around pretending to be swans?)

Nothing in the universe can equal the greatness of music critics. Think of it: they don’t write music, they don’t perform music, most of them not even had any serious musical education in theory or music history, and yet – purely as a result of their innate gifts – they can judge any musical work of any period, and any performance by any musician or ensemble or orchestra or opera house, no matter what. Their dedication forces them to endure an infinite range of musical experiences and while they invest all their energy in conveying to the world the results of their penetrating wisdom, and while they may complain bitterly about the failures that sprinkle music life, they never ever complain about their plight, which is fed by the high-minded idealism they know is the fundamental requirement of their noble task (and they don’t even complain about the meagre pay they get for their sacrifices).

Tosca not a master piece? Since the 18th century, composers have desperately tried to meet the aesthetic requirements of critics, and what we see is how often they failed to meet their standards. And with opera, they continuously failed to understand what the art form is about – they have continuously made the grave mistake to think it’s the music which carries the plot, which transcends the literal front side of the narrative and creates a symbolic metaphor as direct emotional experience, whatever the plot is. How could they be so stupid! Critics have always explained that it is the other way around, that it is the plot that is the heart of opera, and never the music. Did composers listen? No, they did not. Do audiences understand why Tosca is not a masterpiece? No, of course not, because they fall into the same aesthetic trap as the composers. So, critics are much to feel sorry for, since their insights are ignored again and again, but we can still admire their heroism: they stick to their guns in a hostile world, keeping the flame of musical insights burning in the darkness of ignorance.

You evidently read just the headline and not the essay, whose diversion into “Tosca” as drama wasn’t part of the musical assessment of performance so much as a thoughtful and informed literary musing based on a lifetime of reading and listening, however one may agree with the writer’s thinking.

You write, “Tosca not a masterpiece?” in answer to the writer while he himself said, “Its many admirers are right to call it a masterpiece,” then goes on to say, “But a masterpiece of what kind?” A reasonable question and a good jumping off point for a reasoned discussion about its effectiveness as drama.

The point of music criticism is to start or to advance an ongoing conversation about art — and decreasingly in our time, to treat performance as news that’s worthy of being reported in our papers of record. If no one talks or writes about it, a performance is an evanescent event that only those who were present will remember; if someone writes about it, it’ll be there for historians to mine forever.

And if no one talks or writes about the art form, it could mean the art isn’t important enough to remember. In this instance, the critic Macaulay — who has very reputable bona fides as a writer — is no more in love with his own words than you are.

‘Ha!’ (Mefistofeles in Goethe’s Faust II, 3rd Act, 4th scene, in the translation of Diana Stutterford, Oxford’s World Classics 1998)

‘ere. ‘ere. Well said! Good for you !!

You are so right and in Austria they call them rightly ‘Gescheitscheisser’ like this mediocre writer as most are

It’s such a fabulous opera conducted by the greatest and sung by the greatest, Callas was but many others did

It’s such a ridiculous article not even worth posting

ROH disastrous casting by overrated and definitely overdue German Katona just pulled a bad cast together like he often does

Soprano totally overrated and no Verismo singer all, Scarpia weak and Cavaradossi what you mostly get nowadays

Quality isn’t what counts nowadays, it’s wokeism especially in UK and US (there the audience abandoned the institutions ruined by low lives like this critic)

Hardly read any bigger rubbish here but it’s the Zeitgeist

I’m curious as to what exactly is ‘woke’ about this casting?

There is at least one music critic whose articles are themselves often miniature artistic masterpieces, in terms of musical insight, literary expression and… humour. I heartily recommend to all the superb English translation by Henry Pleasants of the music criticism of HUGO WOLF, the great (greatest?) German song composer.

There once was a music critic like Robert Schumann… They’re not all ignoramii (as Hyacinth Bucket would say)!

Borstlap: “it’s the music which carries the plot, which transcends the literal front side of the narrative and creates a symbolic metaphor as direct emotional experience, whatever the plot is.”

What’s a symbolic metaphor? And why doesn’t it matter what the plot is?

In opera, the music makes experience general, the audience can engage with it with their own ideas about it. Example: in Mozart’s Le Nozze di Figaro, Figaro protests against the power of the count, which in a literal sense is not interesting for a contemporary audience since the power of the aristocracy has been overcome; but the audience experiences it as a protest against suppression in general and can easily sympathize with the music and the personage.

Thanks, that is at least a lucid explanation. The same could be said of most Shakespeare plays, of course. So how can what the music adds to the plot be defined?

Mmmm…. I think it is this: the music epxplains on an emotional level what is happening on stage. What we hear is the ‘inside’ of things and what we see is the ‘outside’. Hence the curious fact that operas with silly or even incomprehensible plots can remain very engaging because of the music, and operas with great plots but thin or non-expressive music, disappear after their first productions.

Also a libretto which has a type of text which leaves much space for the music to ‘explain’, offers inspiring material for composers. Case in point: Debussy’s great opera ‘Pelléas et Mélisande’ which is a setting of Maeterlinck’s play of the same name. The play, where the text is implicit most of the time, does not seem to work very well as a play because of the blandness and monotony. But with Debussy’s layer of the ‘inside’ of what is happening on stage, the whole thing suddenly comes to life in a stunning way. Example: when Golaud, the jealous husband, violently mistreats a helpless Mélisande, the onlooking grandfather Arkel, powerless to help the protagonists, says: ‘If I were God, I would feel sorry for the heart of men’. This feels as a bland platitude in the play, especially after the violent scene. But in the opera, suddenly a whole world of emotional engagement of Arkel is revealed, in its gripping profundity, with only a few very appropriate chords. And the audience experiences the awful abyss of emotional turmoil of the protagonists in a direct way. Only music can do this….

Agreed – thanks. If only you always wrote as clearly as this!

Oh! But I write ALWAYS as clearly as this…. Maybe you read too fast, or too shortly after a copious meal.

Funny thing is John, this guy’s a former NY Times dance critic (not music or drama). He’s entitled to his opinions obviously, but can they be taken with any degree of seriousness?

Before being appointed chief dance critic of the NY Times, AM was a music and opera critic for the Financial Times

Yes but who cares what he thinks? There are those who like it and those who don’t. If I think it’s a masterpiece, and some critic thinks it’s rubbish, or vice versa, then the critic’s rancid rantings won’t make a jot of difference. I guess most of us are the same. We make up our own minds about works of art through personal encounters.

Critics who evaluate the worth of musical works are hugely overrated. Very few of them have written any pieces of any worth. They are just Don Quixotes, whose egos far exceed their importance.

Those who rate concert performances almost as useless. If you were there, you will have formed your own view; if not, then it’s purely academic – unless, perhaps, the concert is to be repeated, when an adverse criticism migh serve as a caveat. The only time that critics are of some use is of a particular opera production with a run of performances, when they could provide some guidance to would-be attenders on the standard of the singing, playing and conducting.

That being said, the standard of music criticism, like that of parliamentary debate, has declined these last hundred years or so. As evidence, I would cite the ‘Lexicon of Musical Invective’ by Nicholas Sloninsky, a compilation of some of the most amusing critical put-downs. In 1901, the critic W F Apthorp, writing in the Boston Evening Transcript, wrote a stinging dismissal of Tosca, in which he says that Puccini ‘shows a well-nigh diabolical ingenuity in massing together harsh, ill-sounding timbres’.

If I were myself a critic rating music critics, I would judge Apthorp to be far greater than Alistair Macaulay; nevertheless over the last 122 years, the public have begged to differ over their verdicts on what is, to me, an undoubted masterpiece.

Apthorp must have been a nice man.

The reason that critics feel free to passionately deconstruct performers but have become very cautious with new music, is that since Slonimsky’s book they fear to appear in the next edition.

The best of the Puccinis, IMO.

I was at the opening night in 1958 the cast was Tebaldi, Del Monaco and London add the walls of the old Met c,ame falling down, unforgettable Opera came alive!;;;! In this opera the singer is matter!;;

The delusion of some people is really flabbergasting… at the time of the french premiere D’Indy wrote that Tosca was a flop (or he wised it was). In fact, after 120 year the opera is still performed, discussed and analyzed….

Indeed. And, D’Indy is still remembered and generally adored for having composed…having composed…um…

…having composed some extremely beautiful music (especially in the symphonic field) that ignorants won’t even bother to listen to…

https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=aYAXhD_iCE0

Both Debussy and Stravinsky admired Puccini….. and they were really quite stingy with any praise on anything.

“really quite stingy”. Understatement of the year…

Little hope of persuading new people to buy opera tickets when they run the serious risk of being attracted to operas which are tacky, cheesy and vulgar. Imagine the shame! Never mind that they could progress to the works that critics might just, with a little luck and on a good day, approve of.

Stay at home and watch soaps on the TV. Much safer.

Yes, but what about “Tosca”!!??

Insufferable.

But even they cannot hold a candle to the critics of the critics.

Finally a really interesting and thought-provoking “review” on SD. Mind you, if he thinks Tosca is emotionally manipulative, he should give Suor Angelica a try….

The Wikipedia article on Tosca has a nice selection of nasty comments about the work, dating from the premiere. I enjoy, in particular, this one, “”In the 1950s, the young musicologist Joseph Kerman described Tosca as a “shabby little shocker.”; in response the conductor Thomas Beecham remarked that anything Kerman says about Puccini “can safely be ignored”. The article says that Tosca is the 5th most performed opera.

People enjoy being cheaply shocked. Puccini was very skilled in that art.

The so-called ‘problem’ with Tosca is not the plot / libretto, but the music: it is highly expressive in a direct way, and sensationalist, in a devil-may-care way, and that has more than a touch of the indulgent and the vulgar. But the brilliance of the writing, the honesty of the sentiment, and the sweeping drama of the musical narrative makes it all entirely convincing and one forgets any vulgarity that one had noticed.

The same goes for Strauss’ Salome, by the way.

Joseph Kerman shared this revelation more than 70 years ago.

Prima la musica. Poi le parole. Forget about the “plot”. Just listen to the music (and shut your eyes to the puffed-up importance of the stage manager / producer and his or her antics).

Your parameters for measuring “masterpiece “ status are downright silly. There is only one measurement for determining masterpiece status – the music. And most find Tosca to be glorious musically. Remember the critic who referred to Tosca as “…..a shabby little shocker”? He was wrong too.

I remember having read that the wife of that critic used the same phrase about her husband too.

Oh, I thought she was referring to something quite specific!!

Is it possible you have missed a key attribute of Tosca? Puccini is making a statement of criticism about the hypocracy found in government and church leaders. He is drawing on the compelling music of 1,000 years the church has contributed to western music and simultaneously showcasing human corruption in church and government that lies at the heart of those institutions. Feel manipulated? Just as Puccini would want you to. We have been manipulated; drawn in by the beauty and deep historical resonance the church’s music set alongside human failings in its leadership. Tosca IS a materpiece.

Well said John. What is frequently not understood is that Puccini was a superb commentator of the social scene of the time. Tosca is about the abuse of power. Boheme, the wretched choices for women at that time, Butterfly, the outcome of colonialism. All have a serious background made clear by means of drama and music which live in the mind.

My music professor didn’t think so either. He called Tosca “a shabby little shocker.”

The ghost of Joseph Kerman has entered the chat.

I have just read Alastair Macaulay’s biography in his own website, and as we know, these official biographies often tend to embellish and glamourise reputations, academic and professional experiences. Although he did have an association with Julliard’s, said association was in the dance department and not vocal arts or orchestral music. It is, therefore, logical to ask about his professional credentials and intrinsic knowledge when commenting on the conductor’s skill, the vocal prowess (or lack thereof) of the lead singers, Pucccini’s composition and style, the orchestra’s performance or even the artistic director’s decisions and staging. John Borstlap’s comments are spot on in their analysis, irony and sarcasm…

As it stands, Macaulay’s “critique” is but his own personal opinion, which he is, certainly, entitled to but to elevate it to the status of being an “official review” of Tosca (both as an opera in general and as the ROH’s current production) is delirious, to say the least! We can treat it as his personal opinion or make the mistake of ascribing it the real weight of officialdom… If Macaulay makes that mistake and pontificates about areas he has no training in or professional knowledge of, that’s his problem… if we take it as gospel, that’s our problem…

Taste is very personal, and often ever evolving… let him have his… but let’s not give it more credibility than it deserves (and it doesn’t).

Granted, there is a market for everything in the world, and some people (like the FT) will even pay for such an opinion, which would make Macaulay’s opinion profitable (good for him) but still not authoritative (good for everyone else).

Ah… but he’s rubbed shoulders with the glitterati for donkey’s years… isn’t that a qualification? Would a flight attendant fly the plane or tell the pilot how to do it just because both have the same amount of fly time???? Certainly not, because the flight attendant wouldn’t want to endanger his/her own life… he/she had skin in the game… critics, on the other hand, will have no qualms doing so, as they are criticising “the pilots” from the comfort of their own armchairs… so what if that “pilot’s” career crashes because of the critic??? His armchair will still continue to provide him with the necessary dosage of small power to boost his ego and write the next critique.

We all handle money, every day of our lives in myriad different ways… however, I cannot give financial advice or advise anyone else if I’m not qualified to do so… but music? The arts? As long as the person had a hunch, a keyboard and a platform (really Norman?), he’s good to go…

But hey, who am I to criticise, anyway???

Yet another comment from a critic discussing the narrative of a work and not even mentioning the librettist or original playwright … especially for works that are wholesale taken from the play they are based on! Puccini is no more the author of the narrative of Tosca than Mozart is for Le Nozze di Figaro… so credit (or blame) where they’re due, please.

It’s astonishing how so called opera lovers don’t know anything about the pieces they have seen and listened to billions of times. Tosca is a strongly anticlerical drama, written in a time when the Catholic Church was the Italian state’s biggest enemy. Religion is used by the Vatican power as an excuse. Cavaradossi is a student of revolutionary painter Jacques-Louis David, he is probably an atheist (or, in any case, anticlerical) and he thinks that Tosca’s faith is very simple minded. That’s in fact what triggers all the drama: he doesn’t tell her about Angelotti because he’s afraid she might tell her confessor, and he doesn’t trust priests to respect the seal of confession. Writing that this opera “brandishes Christianity” means you did not understand anything about it, not even its plot.

All VERY true.

Whilst I don’t necessarily agree with everything, I appreciate the perspective; and the review read much better than the usual formulaic synopses and superlatives.And is much less self congratulatory than any by Hugh Kerr.

Umm … derivation goes back alot further … howsabout Angelo in ‘Measure for Measure’ ?

Of COURSE Tosca’s a masterpiece ! Just as a ‘problem’ play’s still a Shakespeare play.

But wait ! ‘Dance’ critic ! Ahh !