Book of the month, farts and all

NewsFrom the OUP list:

Sounds as They Are: The unwritten music in classical recordings – (9780197659281)

Richard Beaudoin

In Sounds as They Are, author Richard Beaudoin recognizes the often-overlooked sounds made by the bodies of performers and their recording equipment as music and analyzes these sounds using a bold new theory of inclusive track analysis (ITA).

From the blurb:

Sounds as They Are theorizes non-notated sounds in recordings of notated classical music. It studies the expressive rhythm of sounds made by a musician’s body and sounds contributed to a track by the recording medium itself. The book establishes a typology of unwritten music across four major categories: sounds of breath, sounds of touch, sounds of effort, and surface noise. Audible events including inhales, exhales, finger taps, valve clacks, guitar squeaks, grunts, moans, and wax cylinder hisses are recognized as music and analyzed within the score being recorded. Scores, spectrograms, and audio excerpts combine to create a nomenclature for unwritten music. The book’s methodology is intertwined with the aesthetics and ethics of non-notated sounds, including their reception by sound engineers, critics, and scholars. It uncovers insidious inequalities across music studies and the recording industry, including the silencing of body and breath sounds along lines of gender and race. The book sets forth a theory of inclusive track analysis (ITA), a methodology that makes a comprehensive census of all audible events on a given recording and codifies their musical function. ITA is grounded in the philosophy of pragmatism. With applications beyond classical music, the theory demonstrates the expressive, interpretive, and embodied possibilities that emerge when all sounds are valued coequally.

There could be chapters on footstomping on the podium and humming along at the keyboard.

Mr. Beaudoin, Bravo, bravo, bravo!

This book reveals more about his free time and less about his expertise. If I had the free time to research candid hums, groans, and farts of great musicians I would be living a most boring life, luxuriating in my own lack of creativity.

He chose the right publisher:

Oh, you pee?

It’s not April 1st for a while.

Nuts.

An attempt to create a category of ‘sonic art’ in the margins of music.

John Cage did this already but then as ‘music’.

The German Klangkünstler Helmut Lachenmann used such sounds als sound art:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GWEuqv-9z3w

If you slow a recording down enough, you can insert so much woke garbage between the notes. Let’s call it micro-woking. (Insidious!)

I’ve read the blurb three times and I still have no idea what it says.

I suppose this is potentially interesting especially for a particular sort of record collector although some of the language in the blurb quoted above — for example “insidious inequalities across music studios and the recording industry” and “when all sounds are valued coequally” — suggests to me some mountain-out-of-molehill making is part of the underlying theory.

I know collectors who regard the truly intrusive coughing in Richter’s famous 1958 recording of Pictures at an Exhibition as an integral part of the reading’s magic. Others wish very much they could be removed, and I’d imagine with today’s technology they could be.

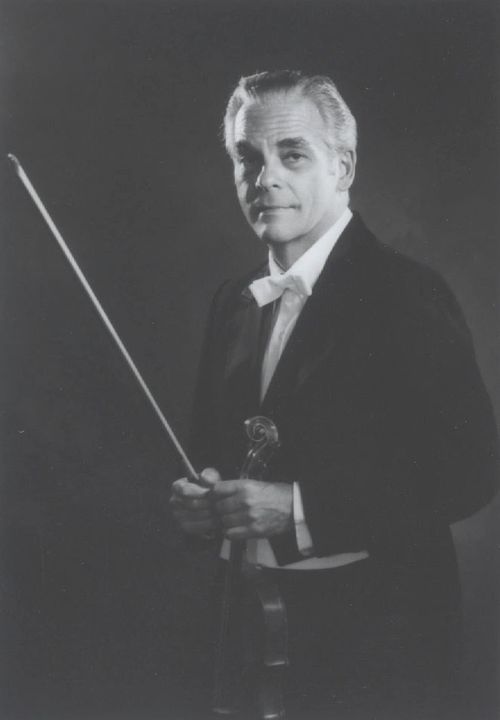

There is a moment in Jascha Heifetz’s stereo recording of Bruch’s Scottish Fantasy where quite clearly you can hear someone’s bow hitting a stand, unless it was Sir Malcolm Sargent’s baton. I have always found it somehow endearing; I know it’s coming and I wait for it, but if some engineer now decided to remove it I would hardly find that to be “insidious.”

I also enjoy the very audible group intake of breath at a key entrance in Rachmaninoff’s Symphony Dances in the Loren Maazel recording.

I know people who would find the recordings to be greatly improved if someone would remove Glenn Gould’s humming — others would find it to be artistic vandalism. Similarly, from a purely artistic standpoint the old and rare 78 rpms of an elderly Vladimir de Pachmann might be improved if an engineer could remove the talking and muttering he was encouraged to engage in by the original recording team, because that was part of his stage persona. It would be taking away history but might well increase the general regard for the recordings.

The ambient noises — maybe even birds singing? — that can be faintly heard in the marvelous “Live” recording of Debussy’s Blanc et noir by Paul Jacobs and Gilbert Kalisch for Nonesuch do no artistic harm to the performance, and capture a sense of occasion I suppose, but even so I would hardly say it would be invidious to remove them.

When Gregor Piatigorsky recorded the Schumann Concerto they were running out of session time due to retakes and for the final side, the end of the concerto, Leon Goossens blurted out an audible “bravo” when the final chord had not yet died out. The engineering of the time allowed for only a partial truncating of the bravo (and hence a very “karate chop” end for what little room resonance recordings of that time had), but it is there for all to hear and Piatigorsky wrote that he enjoyed hearing it and knowing that it was recorded, because it was sincere. I would want that bravo to be retained, but ironically it would be nice if some audio magician could restore the missing resonance of that final chord.

It wasn’t until I added a subwoofer to my sound system that I realized how many recordings, American, British, and European, include the recorded rumble of the local subway!

It is still a point of eternal annoyance to me that Rubinstein’s stereo recording of the charming Chopin A-Flat Major Mazurka (op 59) ends with the audible rumbling of the subway under the final chords. Grr.

John Cage did all this decades ago.

Serious musicology is not worthy of any reporting. Only books on such subjects make the cut.

This is a symptom of the prioritization of research over teaching in academia. Small, high-quality liberal arts institutions seek to turn themselves into second-rate research universities to compete with the Big Boys, and new hires are instructed to give minimal attention as possible to the courses they’re assigned and to their students, in order to focus on publication, where quantity matters more than quality in promotion and tenure decisions. When the most obvious subjects for study have seemingly been exhausted, scholars are compelled to turn to trivia. Don’t blame the author; he’s just trying to keep his job and feed his family.

Before technology made recording possible, these sounds would have been part of the normal audience experience. Perhaps music was never meant to be listened to in a sterile sound-insulated one-person cell?

A whole chapter on Glenn Gould, I imagine.