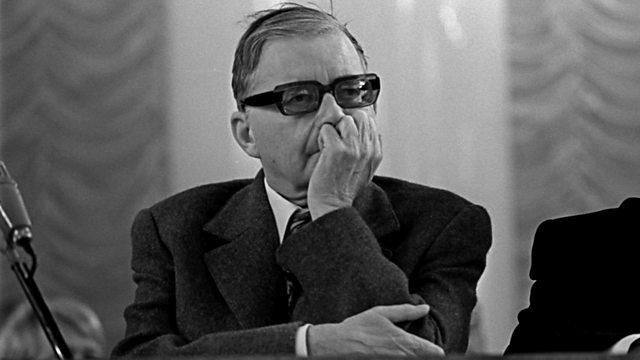

The day Shostakovich prepared to commit suicide

Daily Comfort ZoneEight years ago, we published an article by Emma Denton, cellist of the Carducci Quartet, about the bond she formed with her ailing father over his involvement with the eighth quartet of Dmitri Shostakovich. Her father, Alan Lumsden, died during Covid. Emma is about to perform the 10th Shostakovich quartet with the Carducci Quartet at the Wigmore Hall on January 3rd, 2024.

Here’s a revised version of her deeply moving article:

In 2016 our quartet won a Royal Philharmonic Society Award for our Shostakovich15 project, performing cycles around the globe culminating in a seven hour marathon of all 15 quartets in one day at the Sam Wanamaker Playhouse. As we approach the 50th anniversary of Shostakovich’s death in 2025, our relationship with the quartets continues to deepen.

Our Shostakovich 15 project enabled me to have some incredibly powerful and emotional conversations with my Dad, Alan Lumsden. In 1961, Dad was asked to translate an article that first appeared in the Sovyetskaya Muzyka following the premier of Shostakovich’s String Quartet No.8. The Quartet has always held an almost reverential position in our household and performing it as a teenager at the Royal Albert Hall with Dad watching was an experience that gave me the hunger and desire to become a professional quartet player.

Dad suffered from Alzheimer’s for over a decade and passed away during the pandemic. In the run up to our Shostakovich15 project, Dad’s decline made daily conversations increasingly difficult. However, it was wonderful to find that sitting down together and revisiting the 1961 article, set off a string of memories. He took great pride in recounting how during his last trip to Russia in the 1970’s he managed to flee across the Finnish-Russian border with his friend Dmitri, after being summoned to appear at a tribunal on charges of selling on the black market.

Growing up, I was aware that Dad had a very unusual and eclectic musical career. He was Professor of Sackbut at the Royal College of Music, taught recorder at Birmingham Conservatoire, was a member of the London Serpent Trio, the Early Music Consort of London, provided instruments and played on the soundtrack for Alien, freelanced as a trombonist with many of the top UK orchestras, as well as publishing and editing music. His study was full of weird and wonderful instruments including a medieval double recorder, ophecleides, sackbuts and serpents. He also had shelves and shelves full of old music with a distinctly musty smell. It was in his study that I first learned of Dad’s connection to Russia.

Before University, Dad had to join up for National Service. This was at the height of the Cold War and the powers that be thought that there was an urgent need to train Russian interpreters. It seemed the most profitable way of spending 2 years, particularly as those selected for training as interpreters were automatically commissioned. For the final months of his service, Dad was the official Russian interpreter at the Admiralty and later he was employed by the BBC Russian service to give regular talks on music in the UK. Dad was incredibly passionate about Russian culture and once berated me for reading War and Peace in English, as so much was lost in translation!

On leaving Cambridge, Dad was offered a job with Musica Rara, a London music shop which specialised in importing music. He made 3 extraordinary trips to Russia. Dad used to sit me and my siblings down and recount how he would wear up to 15 Marks & Spencer shirts at a time and would walk up and down the street taking them off one by one as he exchanged them for money or coffee. Underwear from C & A also proved popular! He would use the funds raised to buy manuscripts that were hard to come by in the west, including some Shostakovich scores. Unfortunately, this led to some very tricky encounters with the authorities, which meant that Dad was refused permission to return to Russia. It did however, give him a life long interest in Russian music and Musica Rara published a lot of his finds including many unknown works by Glinka.

After his first visit to Russia and six months after the premier of Shostakovich’s Quartet No.8, Dad was asked by the Musical Times to translate an article written by Yury Keldysh, entitled ‘An Autobiographical Quartet’. Dad told me how difficult this was at the time to translate from the Russian and still preserve a good sense of the meaning. His article has become a fascinating read for me. It is a good example of intelligent Soviet criticism, but only really tells half the story of the 8th Quartet. In the article, Keldysh noted the use of quotations from Shostakovich’s earlier works, the ‘lyrical content’, ‘deeply-felt emotion’ and the dedication to ‘victims of fascism and war.’ But interestingly that is almost as far as it goes. Perhaps in 1961 Russia there was a resistance to delve deeper. From what we know now, it seems that Shostakovich was very near suicide at the time, partly as a result of being coerced into joining the Soviet party. Shostakovich’s friend Lev Lebedinsky provides an insight into Shostakovich’s desperate state of mind:-

‘Shostakovich dedicated the Quartet to the victims of fascism to disguise his intentions, although, as he considered himself a victim of a fascist regime, the dedication was apt. In fact he intended it as a summation of everything he had written before. It was his farewell to life. He associated joining the Party with a moral, as well as physical, death. On the day of his return from a trip to Dresden, where he had completed the Quartet and purchased a large number of sleeping pills, he played the Quartet to me on the piano and told me with tears in his eyes that it was his last work. He hinted at his intention to commit suicide. Perhaps subconsciously he hoped that I would save him. I managed to remove the pills from his jacket pocket and gave them to his son Maxim, explaining to him the true meaning of the Quartet. I pleaded with him never to let his father out of his sight. During the next few days I spent as much time as possible with Shostakovich until I felt that the danger of suicide had passed.’

The use of his initials DSCH as a musical monogram woven throughout the work points towards the intention of the Quartet to serve as a ‘requiem’. Yet Keldysh finishes the article by criticising the ‘monotony of thematic material’ and the ‘tiresome repetition of fragmentary melodic particles.’ In performing the Quartet we find the opposite to be true. Within the complete cycle, it often has the greatest impact on the audience and it is perhaps the economy of melody and musical material that helps.

A lot has been written about Shostakovich since Keldysh’s article appeared, much of it conflicting and contradictory. The one certainty is that his music has had a profound affect on audiences and performers alike and on a personal level, it helped me reconnect with my Dad during his last few years on a level I no longer thought possible and for that I will always be grateful.

Emma Denton

What a touching article! Thanks for reprinting it. The Carduccis, who regularly play at Holywell Room in Oxford and are very much loved by the Coffee Concert community, recently performed a quartet by Shostakovich that (and a Beethoven quartet) was received with great enthusiasm. They are very wonderful musicians.

Well done. A great story.

It explains the somber sound of that music. I am now listening to the Emerson Quartet playing it.

In Wendy Lesser’s Music for Silenced Voices: Shostakovich and His Fifteen Quartets, she writes that Maxim “has repeatedly and emphatically denied the story about the sleeping pills.” There’s more, but for that please read this monumental work.

Unbelievable. And very moving. Thank you for posting this.

I spent time with Alan Lumsden rehearsing for the 400th birthday party for the serpent, organised by his fellow Serpent Trio member, Christopher Monk. He was musically demanding, yet managed to be kind as well to this fledgling serpentist – I had only had the thing three weeks! He insisted on me sitting next to him, on either first or second parts – at the time it felt like so he could berate me more easily, but actually it was to help me achieve his high standards. I use scale and rhythm books of his in my teaching almost daily with students; he created effective ways of teaching intonation via scales. And I have a lovely set of Devienne duets arranged for serpent by him, that sit well for tuba, euphonium and trombone. Fabulous man who won’t be forgotten.