Exclusive: Inside the Women in Classical Music symposium

NewsSusan Hall reports exclusively from the Dallas conference on women in music:

At the beginning of the 20th century in America, women ruled the musical roost. They performed on the piano and sang for friends in the comfort of home. Music was considered a feminine taste. Men who enjoyed beautiful notes and phrases hid their appetite for them..

A Mrs. Oates, inspired by a visit from the touring Metropolitan Opera, escaped from her Atlanta parlor and created headlines when she headed to Chicago to launch an operatic career. Her husband snagged her en route and swept her home.

Men took over music when raising money for symphony halls and opera houses became part of their muscular function as captains of industry. The story of the next hundred years is familiar. No one knew about Fanny Mendelssohn, the composer. Ethel Smyth got one performance at the Metropolitan Opera and disappeared.

Some names shine in the 20th century. Sarah Caldwell conducting in Boston added sizzle to music’s steak, but couldn’t keep the cash flowing. Diva Beverly Sills ran Lincoln Center and then the Metropolitan Opera. In his recent book on Lincoln Center, a former President of Juilliard snidely dismisses Sills as a leader, attributing her ‘failures’ to her diva personality. Yet Sills often remarked that in her executive function she daily sat at her desk and got work done.

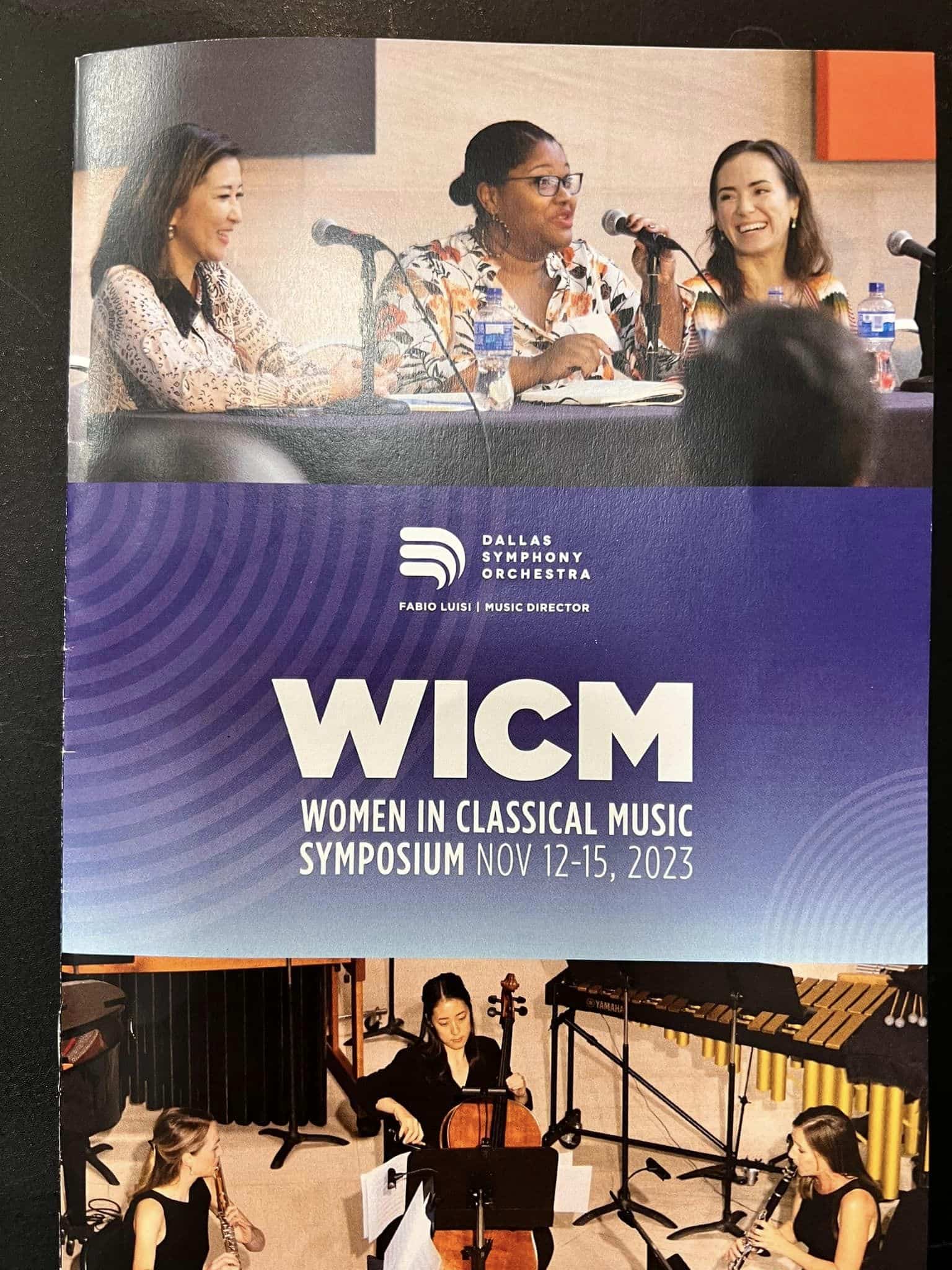

At the Women in Classical Music Symposium held in Dallas, women composers, conductors and CEOs took up Sills’ theme and asked to be judged on their work. Not as women. Not as women of color. And certainly not as anyone on the highly refined LGBTQIA+ spectrum.

Withstanding slights, helping hands (mentoring and educating) and focus on work are offered as key in Dallas. Note Barbara Hannigan, who just made a major American debut in Cleveland. She has said, “When I get on the podium, I am not a woman. I am a person doing their job.” Joana Mallwitz offers educational introductions for the works she performs. Both women attract audiences.

Marin Alsop was almost invisible at the Dallas event. Her notion that conducting is about gestures and women’s gestures are different than men’s is slipping away.

The offensive movie TAR was represented by Natalie Murray Beale who guided director Todd Field on musical matters. Tar the conductor was hurtful to her partner and her orchestra. Nothing this mean-spirited invaded the Symposium.

Leonard Bernstein’s protegee JoAnn Falletta did not turn up, but her spirit did. Leon Botstein of Bard recently invited her to conduct The Orchestra Now at the Rose Theater where she created a glorious aviary with her musical selections. For years Falletta has led the Buffalo Symphony, one of the smaller, local symphonies that may hold hope for the future of classical music. Falletta is an important part of her community, and enjoys being greeted by her first name when she shops. Her local, community-based path (minus talk of baking and babies) was often discussed in Dallas.

Of course Falletta deserved a bigger job. Yet, as Dallas Symphony CEO Kim Noltemy, the instigator of this Symposium, said of her own career: Make decisions with no regrets and no recriminations. As a mother, Noltemy did not pursue the “in, up, out” career trajectory. Her choice. Now in mid-career, CEO Noltemy is one of the most thoughtful and exciting executives around.

Community outreach is critical. In the US, there are many different communities. In the Central Valley of California–not the cool Los Angeles, San Francisco and Napa, Rei Hotoda leads the Fresno Philharmonic. A local farmer grows peaches preferred by the toney French Laundry restaurant, ($400 a person for a simple meal). Hotoda commissioned a work about him. And she is developing a work honoring survivors of the concentration camps built to contain Japanese during the Second World War. Many members of her community are their descendants. Hotoda is not going to dumb down the works she commissions.

Which leads us to the critical and not often openly addressed problem in America. We do not educate. Period. The job of elementary music education is left to struggling music institutions. Lincoln Center claims to have answered this call. Can a giant disco ball obscuring the three neo-Fascist style buildings at the center of the Lincoln Center complex help do this job?

The Symposium offers an alternative path to classical music’s survival. Return to normalcy where people are judged by their work. This path is surprising, provocative and warm in the style of the Symposium’s founder.

Susan Hall

Comments