My year in pursuit of Krystian Zimerman

Editors ChoiceThe pianist Zsolt Bognar has spent much of the past year immersed in an award-winning Szymanowski album and its elusive performer. He takes up the story here.

A few days ago in London, the 2023 Gramophone Award in Piano went to the veteran Polish pianist Krystian Zimerman, for his Szymanowski album released a year ago on Deutsche Grammophon. My search for adequate words to describe the recording invited a year of listening, debates with fellow musicians, and even world travels, to seek insights into its unique musical language, performance, and masterful engineering.

Already six months after intending to share written impressions of the album—and still without anything to show—I traveled from Cleveland to witness Krystian Zimerman in recital in Amsterdam and Duisburg, wherein some of the featured Szymanowski works were programmed. The hope was that attending the performances would yield answers, but the enigma remained and words remained elusive. I ordered the available 180g vinyl pressing with its elegant program notes by Jessica Duchen, as well as the CD—even purchased a new audiophile system—playing the recording for friends and colleagues on repeated listenings to its remarkable presence and narrative power.

The album centers around the monumentally difficult Polish Variations Opus 10, a work whose performances and unofficial recordings by Zimerman I wrote about here [https://slippedisc.com/2020/02/krystian-zimerman-wont-you-please-come-home/], as well as a prismatic selection of shorter works. For reasons unclear, some of the selections were recorded in 1994; the remainder were recorded in Japan in 2022. In an incredible feat of production, these are sonically matched. Each component of the album deserves mention as integral parts to a compelling achievement: an musician in his prime, the venue in Fukuyama, designed by legendary acoustician Yasuhisa Toyota, the engineering team, and the extraordinary Steinway instrument.

Szymanowski’s output as composer is largely unknown to most audiences. As such, stylistic comparisons are tempting; here in selections ranging from 1899 to the 1920s, the music ranges from radiantly idealistic post-Chopin, post-Scriabin explorations, to darker visions in the Masques, Opus 34, that in fleeting and veiled gestures anticipate expressionistic outcries of Alban Berg and Béla Bartók.

Zimerman in the concert hall and Zimerman in the recording studio are two separate universes. The two in recent years have come closer together, as with the Schubert Sonatas album of 2017, but the differences are clear. Whereas his performances characteristically deploy narrative risks, acoustical explorations, and metaphysical reactions to the energy of an audience, his recordings bring a more controlled narrative, deliberate in pacing, clarity, and voicing. A pianist friend of mine indeed described this album as “a masterclass in timings and colors”.

The album’s recorded sound embodies breathtaking warmth and presence. As expected, it is a showcase of the pianist’s crystalline craft and arresting rhetoric.

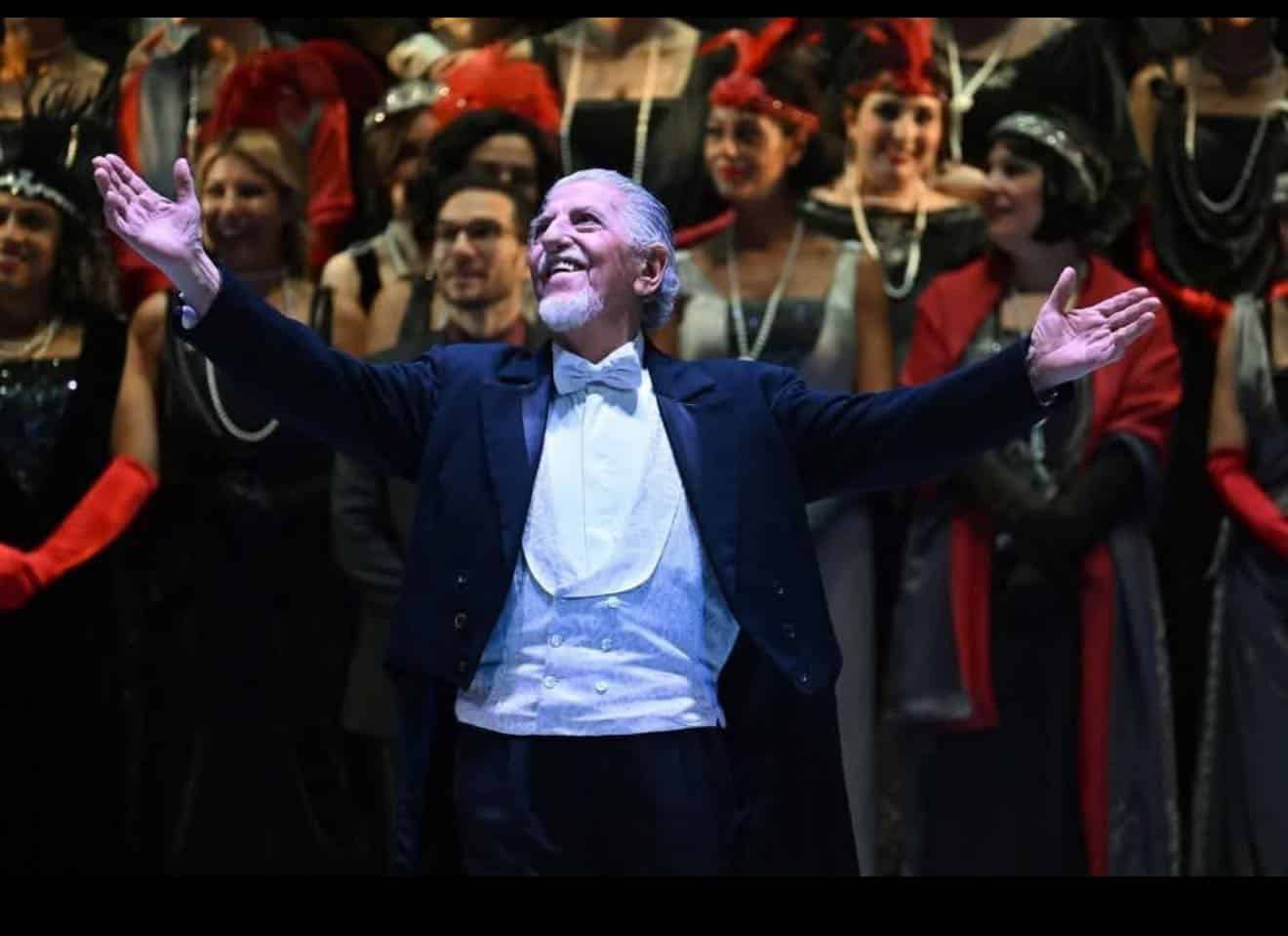

As for what I witnessed in the concert hall, Krystian Zimerman—at 66 years young—takes to the stage with fascinating duality: the magnetic presence of a king, yet with an unpretentious and good-humored enthusiasm in sharing this music. For those fortunate enough to witness Zimerman’s upcoming November and December recitals in Japan, the Polish Variations appear to be programmed along with works of Chopin; I plan to attend with the same sense of awe as I had in Europe.

Despite my months-long journey of listening and compulsive travels, my attempt at a review lends no special insights into the music on the album, but thankfully words are ultimately only peripheral. Krystian Zimerman reaches a new level in his recorded legacy and pianistic craft, one whose music will continue to reveal its message through time.

Comments