The man who made the modern New York Philharmonic

OrchestrasOur friend Valerio Tura has written an appreciation of Bruno Zirato, who was Arthur Judson’s executive arm at the New York Philharmonic Orchestra. Judson made the policy, Zirato made it happen.

He joined the orchestra in 1927, having spent seven years as Enrico Caruso’s secretary. He went on to be associate manager (1931-1947), co-manager (1947-1956) and managing director (1956-1959), drawing a salary as a contracted advisor until his death in 1972.

Here’s Valerio’s article, translated from the Italian.

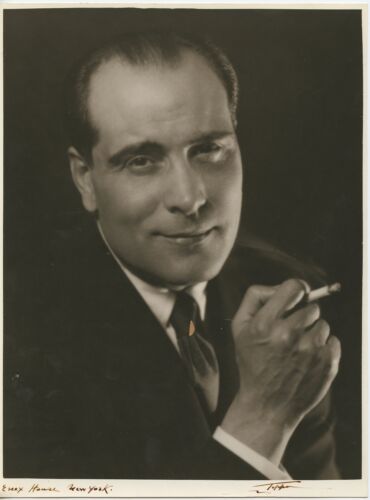

Bruno Zirato (1884 – 1972).

A life for music: between Scilla and Manhattan.

Bruno Zirato was born into a middle-class family in Reggio Calabria on September 27, 1884.

His real name, however, was not Bruno Zirato: it was Czar Bruto, immediately called Zarino by everyone. On October 2, his father Giovanni Simone, christened him with the commanding royal name of Czar Francesco Bruto (Francesco in memory of his grandfather…). At the time, Giovanni Simone was ‘Cavaliere Giansimone’, a respected civil servant. He finished his career as chief clerk of the Catanzaro Court of Appeal.

From an early age, Zarino developed a curiosity for music, especially opera. In one of his writings, he recalls that as a child, his maternal uncle Peppino used to take him to the theatre every now and then (that very same theatre in Reggio Calabria that would later be almost completely destroyed in the earthquake of 1908), sneaking him in under a large cloak and then holding him on his knee. The first unforgettable occasion was a Il Barbiere di Siviglia. Afterwards, he kept humming to himself Berta’s aria “Il vecchiotto cerca moglie”, all night long. The tune had stuck in his ears.

The condition of the family allowed the children to study. For a while, Zarino studied in Rome, at the college of San Pietro in Vincoli. At that time, he developed a certain talent for writing and he collaborated with Il Giornale d’Italia. Back in Reggio, at the beginning of 1912 we find him collaborating with the same newspaper, and also with some Neapolitan newspapers. Every now and then he signs an article, probably poorly paid. This activity lasted for a while, but Zarino realized that journalism was not his future. The earthquake had turned the city upside down, life was difficult, prospects poor. Being ambitious, Zarino was chomping at the bit. He sensed that the world was changing rapidly, and he realized that, at twenty-seven, he still had no social standing, Reggio is too small for him, so he thinks that perhaps he must seek his fortune elsewhere. Paris attracted him. He has studied some English, so his curiosity about America was also strong. Zarino collects some information, knowing that, in those years, New York was one of the most vibrant cities in the world, thanks to the talent and industriousness of waves of European migrants, and to the robust economic growth following the Civil War. He consults Michele Augimeri, a well-travelled family friend. Augimeri encourages him to leave, but points out that the name Tsar might be a problem in a country like the United States, where the principles of democracy are deeply rooted, and where a reference – even just in the name – to the monarchy can create problems. And so Zarino Bruto becomes Bruno Zirato: just a simple anagram. It is not clear how the name change was made official, but as it happens in the first weeks of 1912 Bruno Zirato boarded a train, left Reggio Calabria for Paris and in the Summer boarded a ship for the United States.

However, in the Bruto family there was another story going around. Zarino was definitely a handsome young man – tall, elegant, with sparkling eyes and a brilliant smile, along with a reputation as a “Don Juan”. The story (not a proven fact…) goes that, at the time, Zarino was the lover of the wife of a “bigwig” of the Reggio Prefecture: the vivacious lady was much younger than her husband, through an “arranged” marriage (a practice widespread in some areas of Southern Italy, at the time). The husband, suspicious of certain details, comes home earlier than usual one day. Zarino hears a noise. Alarmed, he jumps out of the lady’s bed, gets dressed as quickly he can, climbs over the window, and tries to hide by clinging to the outside of the windowsill. The husband does not believe his wife, who tells him that she was having a nap, looks out of the window and sees Zarino dangling down: with a shoe he hammers poor Zarino’s fingers, until he lets go, drops into the garden and runs away. The story going around in the family was that after quickly retrieving the bare minimum from home, he ran to the station and jumped on the first train to Rome…

In short, be that as it may, Zarino Bruto, now Bruno Zirato, for one reason or another changes air, as well as name. And who knows if the change of name was a way to cancel track of him…?

Cross-fading… Zarino/Bruno spends a few months in Paris, where among other things he meets a Kansas City doctor, a certain Nevins, who convinces him that a brilliant young man like him will certainly be successful in the United States. And so, on August 17, 1912 Bruno leaves Le Havre on the ocean liner named “Philadelphia”. On August 27, he disembarks in New York, queuing up at Ellis Island with high hopes and little money – a small supply put aside from his own meagre journalistic earnings, and perhaps some more money sent by his father.

We should not imagine Zirato as the typical southerner, with a cardboard suitcase tied with a string, who goes to America and works as a labourer, or as a porter. An extrovert and uninhibited temperament, Bruno quickly establishes contacts in the Italian-American community. The editor of the newspaper L’Araldo Italiano asks him to write a few articles; a Brooklyn professor gives him a few English lessons; he goes to the theatre with an elderly fellow Calabrese native, a certain Tigani, a melomaniac. To make ends meet, he teaches Italian. He has pupils of the New York bourgeoisie eager to learn the language of Dante (a century earlier, Lorenzo Da Ponte, who had arrived in Manhattan after some time in Philadelphia, did exactly the same thing… did Zirato know?). He also teaches opera singers who want to improve their diction. He collaborates as a lecturer at New York University and at the YMCA (Young Men’s Christian Association). In a diary that Bruno meticulously kept in his early American days, he noted down his income and expenditures with an “eye for the accounts” that would later be useful to him. He often urges his pupils to pay for lessons, and though he is definitely not rich, he takes care of his “good looks”, to maintain a certain elegance (another analogy with Da Ponte?). He buys new shoes and clothes, new shirts and collars. He regularly goes to the barber. As a chain-smoker, he spends a lot of money on cigarettes. He has them made by a Russian tobacconist – first-rate Turkish cut, customized with the initials BZ. Above all, he goes to the theatre to hear opera and operetta as often as possible. Likewise, he reads a lot, books and newspapers, to improve his English.

Things begin to look up for Bruno Zirato. From a basement in the Bronx he moves into a studio apartment on 46th St. in Manhattan. In addition to the Italian lessons Zirato adds a new source of income from a doctor friend. The otorhinolaryngologist Mario Marafioti is another Calabrese who had emigrated to New York. The enterprising Dr. Marafioti is well-known in the world of show-business. He is the “official” doctor of the Metropolitan Opera Company and treats singers. He created the production of “Opera Stars Lozenges”, pills for the voice with a special, highly-secret formula, and is in need of a salesperson. He offers Zirato the job of salesman with regular remuneration. He asks the extrovert Bruno to work for him for fifteen dollars a week. Bruno, with a lot of nerve, asks for twenty. Marafioti accepts.

Business is brisk, Zirato is a familiar sight in the singers’ dressing rooms. Although he is tone-deaf with the raspy voice of a smoker, he knows the operatic repertoire quite well. He knows many scenes by heart, and above all he is very talkative. Therefore, has no difficulties in getting on friendly terms with many of them. He goes to the theatre almost every night, often in gallant company: his fame of a “latin lover” also circulates in Manhattan… Among the singers who went to Marafioti’s for occasional treatment was Enrico Caruso, who, at that time, was at the height of fame in the New World, his notoriety comparable to that of a modern-day pop-star (a few years later, after the tenor’s death, Mariafioti would publish a book: Caruso’s Method of Voice Production).

On December 24, 1914, it was freezing cold. Zirato is queuing at the Met box office, as he often did, to buy a standing room ticket. Massenet’s Manon is on, with Caruso and Farrar singing, and Toscanini conducting. I like to think that Zirato waited for Caruso at the exit to congratulate him and ask him for an autograph, and that this was their first meeting. Let us not forget that Zirato does not go unnoticed, not only for his imposing stature, but above all for his natural communicativeness.

In early Summer 1915, shortly after Italy’s entry into World War I, Zirato organized an “Italian Bazaar” with friends from the Circolo Italiano. This event was to be a charity sale to raise funds to send to Italy for the families of war refugees and of the fallen. To liven up the sales, Zirato invites some singers, Italians or Italian-Americans, to perform at the market, and also later musical gatherings at places like Madison Square Garden to collect donations. Among those who responded were Rosa Ponselle (born Ponzillo) and Nina Morgana, whom we will soon meet again… But Zirato sets his hopes even higher. He decides to ask for help from the most famous Italian, Caruso, and goes to him at the Knickerbocker Hotel. “All right,” the singer replies to him, “I’ll come willingly, I’ll do anything, but I won’t sing…!” The next day Caruso is at the market and draws caricatures (his favourite hobby) of those who donate five dollars at the “Italian Bazaar”. In the end, he himself leaves a generous donation. Later, he let himself be persuaded by Zirato to take part in other similar charity initiatives, even as a singer, no longer just as a caricaturist.

Evidently the extrovert Calabrese Zirato captures the sympathy of the Neapolitan Caruso. Every now and then he invites him out for lunch, asks him to write letters in reply to his admirers, to send photographs, to do some shopping. He leaves Zirato small gifts, as well as – obviously – tickets for opera performances, and allows him to use his car, driven by his personal chauffeur. The frequentation between the two goes on throughout the Summer, since the war prevents Caruso from returning to Italy, and so, at the beginning of the following theatre season, Caruso proposes to Zirato that he devotes all his free time from Italian lessons to act as his personal secretary, for three hundred dollars a month. In those days, quite a good amount of money!

For the next six years, Zirato was not only Caruso’s personal secretary, but also factotum, advisor, confidant, alter ego, administrator, manager, card-games partner, and cashier who dispensed the gifts distributed by the munificent singer. In a word he was Caruso’s shadow, in symbiosis. A few rare photos show them together: at the racecourse, at a party with friends and family, at Caruso’s second wedding to Dorothy Benjamin, and just walking through Manhattan. In a silent movie that Caruso made in 1918 (admittedly of little success…), entitled My Cousin, in which he played a famous Italian tenor in New York, Zirato has a bit part playing himself. We see him holding off admirers at the Metropolitan’s exit, filtering journalists, fans and beggars, at times almost acting as a butler (VIDEO LINK – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BtDG_3o_1-E&t=1820s).

Despite being ill, Caruso wants to be Zirato’s “ring-bearer” when the latter marries, in June 1921, the soprano Nina Morgana *2), whom he had met at the “Bazaar Italiano”. The tenor, prevented by illness from being present at their wedding, sends the bride a diamond ring as a gift. Many years later, in a radio interview, Zirato recounts many personal details of his collaboration with the tenor (AUDIO LINK – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uMhJZyuXgOU&t=339s).

Time passes. It is now the Spring of 1922. A few months have passed since Caruso’s death (August 2, 1921), Zirato is thirty-seven years old and has been married for less than a year. In October, a son would be born, christened Giovanni Enrico Bruno Zirato: Giovanni like his grandfather, Enrico like Caruso. In the meantime, Nina’s artistic career takes off with regularity, especially at the Met, contributing to the family budget. For a number of years, the fees his wife receives from the Met and elsewhere, including for concerts, is the couple’s main source of income. After Caruso’s death, and after having continued to work for his widow Dorothy for some time handling practical and administrative tasks, Zirato has to make do. He does a bit of everything. He works as an artistic agent for, among others, Lily Pons and Ezio Pinza; as a “talent-scout” for Gaetano Merola, director of the San Francisco Opera Company, and for Ottavio Scotto, director of the Teatro Colón in Buenos Aires. Occasionally the Met also asks Zirato to collaborate for the same purpose. He works as an “envoy” in New York for the Milanese agent Emilio Ferone, of the Lusardi agency, at that time the “longa manus” of La Scala; together with the South American artist Samuel Emilio Piza, he organizes a season of concerts in the salon of the Plaza Hotel, the “Plaza Artistic Mornings”. He also writes, writes, writes… In addition to L’Araldo Italiano, Zirato writes for such magazines as Musical Courier and Musical Digest. He also writes a biography of Caruso, with the help of journalist Pierre Key in the role of “editor”. But the collaboration is difficult. Perhaps for this reason the book will only yield a “succès d’estime”…

During his years working with Caruso, Zirato skilfully established relationships in the classical music world. Giulio Gatti-Casazza, the legendary general director of the Met, is among his best friends and generous with advice. Even Toscanini is part of Zirato’s network of relationships, having left the Met in 1915, and returned to the United States regularly from 1926 onwards as conductor of the New York Philharmonic Society (which a little later, in 1928, would merge with the New York Symphony Orchestra, taking the name New York Philharmonic Orchestra, with the acronym NYPO). So is Clarence Mackay, wealthy “boss” of the Postal Telegraph and Cable Corp., philanthropist and president of the NYPO. In a radio interview (TWO AUDIO LINKS – https://digital.library.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metadc28124/m1/#track/6 + https://digital.library.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metadc28124/m1/#track/7),

Zirato recounts a time when Mackay called him to work for the Philharmonic. Relations are not easy between the temperamental Toscanini and the then general director of the NYPO, Arthur Judson. Mackay, perhaps trusting in Zirato’s “facilitator” skills, wants him as a buffer between the two. Zirato quickly absorbs the essentials of Judson’s professional skills, his ability to sense the potential for change, his relationships, his ever vigilant and rigid control of the administration. Unlike Judson, Zirato is not a musician, but he has a habit of always keeping a watchful eye on the accounts, a trait appreciated by Mackay. (When asked what his musical instrument is, Zirato replies “The cash register…!”). One of the first tasks entrusted to Zirato is to work on the organisation of the NYPO’s complicated, though successful tour of Europe with Toscanini, in 1930 – a project that, despite the obvious difficulties, all the protagonists want with obstinacy and courage, in the aftermath of the great economic crisis of 1929. When Judson’s deputy, Edward Ervin, returns from the tour, he retires. Zirato is called upon to take his place. He is soon promoted to the role of “Associate Director”, and, a few years later, to that of “Co-Manager” because Judson had so many affairs that distracted him from the NYPO’s activities. Zirato is now the orchestra’s “man-machine”, the main point of reference, always available to everyone: the members of the “board”, the newspapers, and the public. Above all, he is pivotal in every negotiation with conductors and guest artists, with the orchestra’s instrumentalists and their powerful unions… Gradually Zirato, willingly or unwillingly, also helps Judson in his work as artistic agent, representing conductors and soloists.

At the helm of the NYPO Zirato would have relationships with some of the greatest musicians of the time: Szell, De Sabata, Stravinskij (who nicknamed him “Sparafucile”…), Klemperer, Karajan, Munch, Copland, Cantelli, Leinsdorf, Ravel, Boult, Monteux, Ormandy. He would take the orchestra to important heights. He helped develop the work barely started by Judson for wider broadcasting of the concerts, first on radio, then on television. He invested his energies in the production of records, and in increasing the number of national and international tours. Of particular importance among these is NYPO’s very first tour of continental Europe after the end of World War II. The tour is promoted in collaboration with the State Department, in the autumn of 1955: twenty-seven concerts conducted by Mitropoulos, Cantelli, and Szell, in fifteen European cities, including Berlin and Rome, capitals of countries that not many years before had been enemies of the United States, as well as three other Italian cities, Naples, Milan, Perugia. Crucial for the successful organization of the tour was Zirato’s idea to solicit help from the legendary Anita Colombo, formerly Toscanini’s personal secretary and later the organizational “pillar” of La Scala. At the same time, Zirato asserts his strong personality, which echoed inside and outside the orchestra. One significant episode stands out. Many singers frequented the Zirato-Morgana family. The occasions were often dinners in their flat at 322 West 72nd Street. The famous African-American bass Paul Robeson, known for his decidedly “liberal” political ideas (during McCarthyism his name would end up on the “black list” and his passport would be withdrawn), was occasionally invited to the family. One day, during a fund-raising event for the NYPO pension fund, a board member tells Zirato that he does not think it is appropriate for an orchestra executive to invite a “coloured person” home. Zirato’s response, as heard by those present, is cut to the chase: “All I need to know about Paul Robeson is that he has one of the most extraordinary bass voices I have ever heard!”

Zirato would easily win the utmost trust of the conductors who gradually took over with stable relationships at the helm of the NYPO, among them Bruno Walter, to whom one of the most important episodes in Zirato’s career is linked.

On the evening of November 13, 1943, Walter (no longer very young at seventy-seven) calls Zirato over the phone to tell him that he is in bed, has colic, is debilitated and does not feel able to conduct the concert the following day, Sunday, at three o’clock in the afternoon.

The first idea, to immediately call Artur Rodzinski, who a few months earlier was appointed Musical Director of the NYPO, turns out to be infeasible given the short notice. Rodzisnki had just left for a rest period at his home in the mountains of Massachusetts, and is now blocked by a snowstorm. The idea of cancelling the concert is immediately discarded: there is no time to warn the audience, nor to cancel the live radio broadcast. Zirato has an intuition. He tells Walter that he intends to entrust the concert to a young conductor, just over twenty-four years old. The previous year, this guy had made a good impression as an assistant to Serge Koussevitzky, who brought him from Boston, and who occasionally comes as an assistant to NYPO rehearsals, showing talent and flexibility. Walter leaves the solution of the problem in Zirato’s hands. A few minutes later, the phone rings in the young conductor’s small flat. He is having a carefree evening party with family and friends, playing the piano for mezzo-soprano Jenny Tourel, with whom he has just finished a chamber concert at Town Hall. On the other end of the line is Zirato, who says to him – we may imagine the phone call – in a light tone: “Get ready, Bruno Walter is not so well, Rodzinski is buried in snow, maybe you’ll conduct tomorrow’s concert…! Take a look at the music on the programme.” The playbill announces Robert Schumann’s Manfred Overture, Miklós Rózsa’s Theme, Variations and Finale, Richard Strauss’s Don Quixote, and the Prelude from Richard Wagner’s Meistersinger. The young conductor, perhaps not taking the call too seriously, continues to play and have fun in friendly company, a witness will say until four in the morning… The next day at nine o’clock, half-asleep, he answers another phonecall from Zirato: “Come here at once,” he tells him, “Walter won’t move from his bed, Rodzinski will never get here in time, the concert is yours!” The other stammers: “And what about rehearsals…?”. And Zirato: “No rehearsals. Just run here. I’ll explain later.”

The young conductor grabs the chance with courage and a touch of recklessness. He more or less knows the music on the programme, and that’s enough. He has just enough time to notify his parents and some friends, dress in an afternoon concert outfit, make a quick visit to Bruno Walter (who receives him wrapped in a blanket) for a few checks on some passages of the scores and on the tempi, to have a word with the orchestra concertmaster, John Corigliano, and with the two soloists of the demanding Strauss score, the cellist Joseph Schuster and the violist William Lincer, and then it is already concert time. While the young conductor waits in the wings for the moment to take the podium, Zirato steps out onto the proscenium to inform the audience of the change: he concludes his brief speech by introducing the replacement conductor and saying “He will seek to entertain you!”

As the US is in the middle of World War II, the concert opens with the Star Spangled Banner, to which the entire audience joins in chorus, then continues with increasing success. The chronicles note that the concert is greeted by ovations for the conductor, who during the interval receives a telegram from his mentor Koussevitzky: “I’m listening to you on the radio: magnificent!” Thus, Zirato’s intuition began the young conductor’s career. His name was Leonard Bernstein, known to his friends as Lenny.

The first three pieces of that legendary concert have fortunately come down to us (THREE AUDIO LINKS – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VSaI11O5WzY + https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Q0fpNSKViso + https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7bOVpiuT2kk).

Later on, Judson too (due to accusations of conflicts of interest and lack of assiduity in the management of the NYPO, due to the increasing attention required by his many affairs, and above all due to controversies in the newspapers and disagreements with the “board”) retired definitively in 1956. Bruno Zirato is officially appointed the sole Managing Director of the NYPO, a position he would hold until he retired from the front line in 1959. Not without, however, having gotten the “board” approve the appointment of his “discovery”, Leonard Bernstein, as “Musical Director”, as the successor to Dimitri Mitropoulos. Zirato would nevertheless remain as a paid advisor and an esteemed, “éminence grise” of the orchestra and of Lenny, until the day he died on November 28, 1972.

The general public has not known his name, just as few know the names of those behind the scenes: impresarios, organizers, key-people, who, however, live and work, far from the spotlights that illuminate the successes of great artists, actors, singers, directors, conductors.

Valerio Tura

*1) This work would not have been possible without the cooperation of Bruno Zirato’s granddaughter, Nina Zirato-Goebert, and of the historical archive of the New York Philharmonic Orchestra (NYPO), who generously made available texts, documents, images. Among other things (articles, radio interviews, journalistic reports, documents, letters, etc.), some notes were particularly useful, written by his son Bruno Zirato Jr. (1922 – 2008): after a brilliant career in radio and television, the latter probably planned to develop these notes into a book about his father’s life, but it was never written.

*2) Nina Morgana (1891 – 1986), lyric soprano (AUDIO LINK – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q0Y8k6UeX9E), made her Met debut in 1920, at the age of twenty-nine, with Rigoletto (Gilda), and then sang regularly at the Met until 1935: her last performance was in La Bohème (Musetta). Her repertoire included Sonnambula, Pagliacci, Il barbiere di Siviglia, Carmen (Micaëla), Guillaume Tell (Jemmy), Les Contes d’Hoffmann (Olympia), L’elisir d’amore, among others. Among the great singers with whom she shared the stage, in addition to her friend and supporter Enrico Caruso, are Gigli, Lauri-Volpi, Pinza, Martinelli, Pertile, and among the conductors Marinuzzi, Toscanini, Reiner, Serafin. In 1966 she was among the guests of honour at the “Farewell Gala”, the last evening in the old Met, before it was demolished and the company moved to the new theatre at Lincoln Center.

*3) Arthur Judson (1881 – 1975), a leading figure in New York and American musical life, as well as the founder of what was to be the origin of the CBS/Columbia empire (radio, TV, records, artistic agency…), had a very long career and a multifaceted personality: violinist (with poor results…), organizer, producer, artistic agent, manager of large music organizations, entrepreneur in the music world, pioneer in the borderland between classical music and the radio/sound industry, even testimonial for advertising campaigns… He often pursued different activities simultaneously, with practices that today’s sensibilities would consider to be in conflict of interest. It must be said, however, that the US mentality of the first half of the 20th century did not see this as too big a difficulty, let alone as something to be censored. And even US legislation would only become more cogent on the subject a few years after World War II. During Judson’ tenure, the NYPO absorbed through “merger” other more or less competing New York orchestras, becoming in fact the only symphony orchestra in the city capable of holding its own against (and often surpassing) the other historical American orchestras: that of Philadelphia (of which Judson was general manager, for a first period even at the same time as the NYPO), those of Chicago, Cleveland, Cincinnati, and Boston.

..and, oh, what a mess he made of the kindly Dimitri Mitropoulos’ music-directorship…constantly impeding Mitropoulos’ open-minded embrace of contemporary music. In this excerpt from William R. Trotter’s excellent Mitropoulos biography “Priest of Music”, the conductor, a patient and saintly man, greatly surprises a colleague whom he met for lunch immediately following a meeting with Zitato:

“That same morning, Mitropoulos and Zirato had had a tense, protracted, ultimately ugly argument about some of the thornier contemporary works Mitropoulos wanted to program during his first season as the Philharmonic’s music director.

“When the conductor finally appeared, somewhat later than expected, Strauss [his friend] was startled by his appearance. Mitropoulos’s color was normally very rosy—on this occasion, his skin was white with anger and his hands were trembling. Since the conductor rarely used profanity, the impact was powerful when he did. On this occasion, he slammed down into his chair and snarled: ‘That son of a bitch Zirato!’

“‘What happened?’ Strauss naturally asked.

“[…] Zirato had taken it upon himself […] to forbid the conductor to schedule ‘excessive’ amounts of modern music in the forthcoming season.

“‘I have to do it’’, Mitropoulos had told him; ‘this is my mission!’

“‘Mission?’ Zirato snarled. “Listen, you are not Saint Francis of Assisi and Carnegie Hall is not a church. You’re lucky you have the damned job. We took you instead of Stokowski because we thought you’d be more manageable. Now you be a good boy and take care of yourself.’

How dare he.

Thank you for this tribute and historic information on arts management. I arrived in NYC in 1957 and had the luck to work with Mr. Judson briefly before he was replaced by Ronald Wilford as head of CAMI.

Wonderfully informative article. Of course, I knew Zirato’s name and of his association with the NYPO, but not much else about the man himself. Thanks for posting this.

In the Don Quixote conducted by Lenny, Joseph Shuster was the solo CELLIST, not the violinist. Shuster was NYPO principal cellist at the time.

Thank you for this remark. The mistake has already been corrected.

Fascinating stuff. Thank you.

Greatly enjoyed this article. However, re: Lenny’s Don Quixote,

Joseph Schuster (as is obvious) was a ‘cellist, not a violinist.

Thank you for this remark. The mistake has already been corrected.

A fascinating story; many thanks for sharing it!

One detail (not directly about Zirato) is striking: in 1943, during WWII, the NYPO program that launched Bernstein’s career contained, in addition to Schumann and Rozsa [sic: not Rosza, as in the article], works of Richard Strauss and Richard Wagner, the one still alive and willing to work under (or with) the Nazi regime, and the other a source of inspiration for it. The U.S. had learned not to repeat its mistakes of WWI, when even Beethoven had been proscribed in some venues as an “enemy” composer. And perhaps it holds lessons for our day, too…

The spelling mistake of the name of Miklós Rózsa has already been corrected. Thank you.

Some details here that are either incorrect or should be researched further.

— After the merger with Damrosch’s New York Symphony, the New York Philharmonic, for decades, was known as the “Philharmonic-Symphony Orchestra of New York”. Look at the labels of the American Columbia 78s of Bruno Walter and others. They can barely squeeze the name of the orchestra onto the label!

–The tale of the Bernstein NY premiere has its variations. I’d consult Humphrey Burton’s wonderful biography of Bernstein, the tale is on pages 114-117. My favorite line is Rodzinski’s to Zirato. Quoting Burton: “Call Bernstein” was the maestro’s immediate reply, “that’s why we hired him.”

Bernstein was the Philharmonic-Symphony’s assistant conductor.

— Conspicuous by his absence is any mention of John Barbirolli. He followed Arturo Toscanini’s tenure in 1936. Zirato’s role in Barbirolli’s term should be a fascinating tale.

FYI, the soprano Nina Morgana, a true soubrette was a Caruso mistress and they conducted a tour of the US together prior to the Zirato relationship. The diamond ring was more than just a standard over the top Caruso present.