Ruth Leon recommends… Let’s Face The Music and Dance – Astaire and Rogers

Ruth Leon recommendsLet’s Face The Music and Dance – Astaire and Rogers

Lovers of Fred and Ginger can argue happily for hours about which is their favourite number. It’s like trying to decide which is your favourite child.

As an experiment, I tried separating the dances from the songs to see which of their pure dance numbers left the most lasting impression. This is the one that came top in my catalogue of epic performances in dance history. Not the most acrobatic, not the most innovative, not the most technical, not the most difficult, not the most complex. It is, however, the most romantic and, although they weren’t trying for this effect, the most sexually charged.

Even without Irving Berlin’s irresistible lyrics, perfectly attuned to the sweeping strings of his music, this is the one. Let’s Face The Music and Dance was written by Berlin in 1936 for the film musical Follow The Fleet and has been sung and danced subsequently by everyone from Nat King Cole to Diana Krall but never, I suggest, with quite the same romantic heft as in the original.

By the way, watch carefully, don’t get carried away, and notice that the entire dance is filmed on a single camera shot with the cameraman ‘dancing’ with Astaire and Rogers so that he is invisible unless you are looking for perfect camerawork, which this is.

The way Ginger’s dress seamlessly wraps around her beautiful legs is as much part of the choreography as the actual steps. An elegant and romantic dance, indeed. Later on in Swing Time, there is another magnificent duet in which they dance to the music of Waltz in Swing Time, also filmed in that single camera shot without any edits. Escapism at its best, especially when it was experienced inside a lavish and architecturally themed Movie Palace.

Alan Shulman’s 1959 arrangement for Raoul Poliakin and His Orchestra on Everest Records: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OyUveMooprQ

Wonderful, thanks. I wonder how many hours they spent rehearsing as Astaire was known for his perfectionism?

Your comment about the cameraman is spot on. These days they would have an idiot running round them with a hand held camer like in Strictly Come Dancing, which makes us dizzy.

Mark Sandrich, the Director, would have been responsible for coming up with that single-take dance sequence. Amazing when you think that the ‘unchained camera’ was still a comparatively new idea and sound on film was not a decade old!!

Out of the despair of Depression USA came the most fabulous artistry via the film musical.

I disagree, thinking the highly sensuous “Night and Day” from “Gay Divorcee” was the best. But you’re right about that excellent single take with “Let’s Face the Music”.

Weights were put into the hem of Ginger’s dress for this number; it had to be altered when it hit Fred in the face during rehearsal! It’s director, Mark Sandrich, would be dead in 9 years at the ridiculous age of 44.

Worth consideration is the staggering contribution to American culture by Jewish emigres to that country. This was the background of Irving Berlin.

I’m currently reading the biography of Samuel Goldwyn and virtually every single man who started the US film industry (except Cecil B. DeMille) was a Jewish immigrant or from an immigrant family. Most of them were manufacturers and wealthy speculators.

Neal Gabler’s book on the topic was even titled, “An Empire of Their Own: How the Jews Invented Hollywood”

Thank you for that excellent reference. I’ll get the book!! There’s probably a lot of cross-over with the fabulously-written Goldwyn biography.

Quite a bit as been written about this film and this particular number. One source says there were 20 takes of this dance alone.

The sources that I found do not address the question I have — as part of the plot to the film this is a dance number in a show before an audience with an orchestra in the pit. Were they dancing to this actual orchestra “live” or was the score dubbed in later?

Standard studio workflow for musicals was (and remains) to pre-record the sound, then actors would dance (and lipsync) to that recording played back. The orchestra you see at the end of the above clip would be merely pretending to have played.

Pre-recording and playback would be the only way to get identical tempos among different camera takes that might be later cut together in editing.

VERY early sound movies like Jolson’s “The Jazz Singer” were indeed shot “live” where the musicians you see are the performance you hear, recorded then and there, but the desire for polish in both sound and sight makes that generally impractical other than for “concert” films.

The very earliest musical films had the small band/dance orchestra seated directly behind the camera. Ergo, “Broadway Melody”, 1929. It was the case that, even then, multiple camera set-ups were used so that all images were dancing to the same tune, as it were, being edited together for the final film. Later playback was cheaper because there wasn’t the need for so much film and so many cameras.

We tend to think of early film as in every way unsophisticated and this just isn’t true. “The Jazz Singer” was partially-synchronized – and not a full ‘talkie’ – as was “The Man Who Laughs”, 1928, (and others, of course) which was shot as a silent film and later partially synchronized because of the advent of sound on film. I highly recommend this latter film for the stunning performance of Conrad Veidt. This film is not, of course, a musical.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=S4-TDtrgtak

Partially-synchronized films were also released as silent films because theatres did not have the expensive equipment to handle sound film for some years.

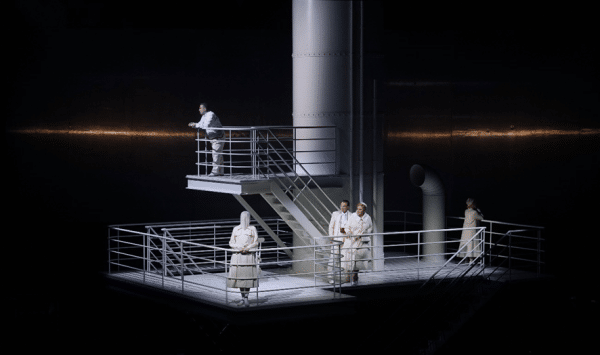

I was baffled for years by the dance floor in this scene until I read a commentary explaining that it was supposed to be the light and shadow from the lighthouse canopy.

Painting shadows on the floor… they’re still doing German expressionism and “Dr. Caligari” in 1936!