An eyewitness account of Gustav Mahler’s final days

Why MahlerIn his forthcoming book on Mahler reporting in the Neue Freie Presse, Michael Haas translates an account of the dying man’s arrival by train in Vienna western station written by a diplomat, Paul Zifferer.

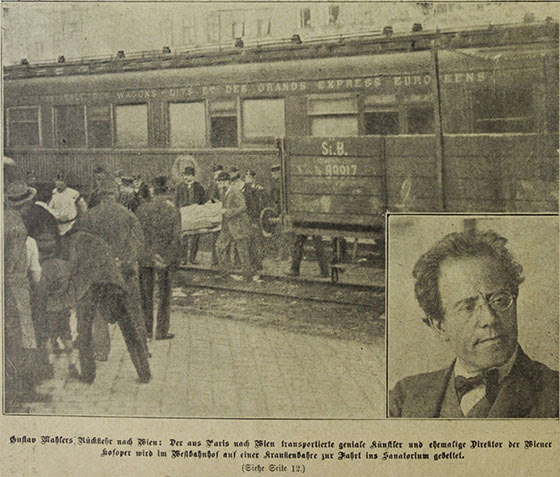

…Medics enter the carriage. They reappear shortly afterwards, jumping from the running board, conferring among themselves. The automobile for the invalid is parked right by the tracks. They attempt to move a stretcher into the carriage but no amount of turning or twisting appears to work with all attempts proving futile. And, watching this, our thoughts turn to the patient trapped since yesterday evening in the narrow bed of the sleeper, all because he had become obsessed by his determination and singular desire to return to Vienna: to come back home. Suddenly we notice some movement in the carriage and carried by two men, we can see Gustav Mahler through the windows. His ravaged body is dressed in a grey summer suit. His noble hands rest gently on the shoulders of the two men supporting him. At first, we only see the back of his head, the black wiry hair, the narrow boy-like shoulders, but suddenly the patient turns his head and one recognises the contours of his face: the broad steep forehead, in which locks of hair defiantly fall, the pointed nose above his thin, firmly pressed lips and the wilful chin. His face is pale and exudes both suffering and fortitude. His movements are defiant, radiating tension and energy, and an intense will to live. His face radiates determination, yet what we see is only a mask.

As they place the patient onto the stretcher, there is a painful movement of his lip that only lasts a few seconds. Immediately afterwards his determination takes over again, his muscles tighten and a red blanket that picks up the sun is tucked around him. The wind plays gently in his hair as if wishing to caress him. And then, Gustav Mahler raises his eyes-the glasses through which he so often shot his stern unyielding looks are missing. An undefinable flickering in his eyes appear, searching and yearning, looking in the distance towards the city growing pink in the first signs of eventide. A smile appears to flutter across his face, but only the corners of his mouth turn upwards for a brief second. Immediately afterwards, his face resumes the expression from before, the determination as if he didn’t want to lose for a moment the resolve that had been necessary to make this long journey…not far away, near one of the freight loading stations stands a simple young worker who has occasionally helped out as a stage hand at the opera. His co-workers all scurrying about their duties really have not got the faintest idea who this sick person is being moved on a stretcher in to a waiting automobile. The young worker, however, does recognise Gustav Mahler from the time when he was still opera director. Moved, he continues to look at him while wiping his eyes with his dirty blue sleeve…

Read on here.

Of greater interest to me, is this ‘blog’ Michael Haas wrote, regarding Berthold Goldschmidt and Mahler’s 10th symphony.

https://forbiddenmusic.org/2013/09/30/berthold-goldschmidt-and-mahlers-10th/

Mahler most likely harbored hopes of a full recovery, prior to his last collapse in Paris (while in transit, more or less). He had purchased some acreage well south (I believe) of Vienna. This was the property where Alma later built herself a home. This is where she and Anna lived for much of the inter-war period. There are quite a few photos of Alma, Anna, and various guests at this house, which can been viewed at Marina Mahler’s “Mahler Foundation” website. For all the heavy criticism that has been dished out towards Alma – some of it surely well deserved – she did do three very important, positive things. She used her money and contacts to get Franz Werfel out of Europe. She helped to keep Schoenberg afloat, financially speaking (as requested of her by Mahler), and she did not opt to toss the sketches for the 10th symphony into the fireplace. To me, those three serious contributions outweigh whatever faults she had.

Fascinating.

I’m delighted to be interrupted from my Beethoven birthday bash with this important Mahlerian news. The Austrian diplomat’s excerpted account reads more literately than Lina Schmalhausen’s prosaic account of Franz Liszt’s final days from her diary. The book, no doubt, will be an interesting read. Julius Korngold’s gripe about Mahler’s famous Adagietto being “bourgeois sentimentality” may be true, but without it and Visconti’s film, there would not be a larger receptive audience to Mahler’s music. The circle of classical music supporters, in general, is much larger because of the characteristic of “bourgeois sentimentality” than in Mahler’s time.

Korngold sounds like Lenin or Stalin.

Lina Schmalhausen’s account of Franz Liszt’s final days are fascinating and appalling. She told the lurid story in much more detail than did the great Alan Walker (whom I once met; he’s the soul of gentlemanliness).

Nowadays, Cosima and Richard would certainly be charged with elder abuse.