First night review: A ballet that will linger long past morbidity

NewsBy Alastair Macaulay, former NY Times chief dance critic, exclusive to slippedisc.com:

The golden “EIIR” tapestry logo remains on the gorgeous red curtains of the Covent Garden opera house a while longer, although its “CIIIR” successor is said to be ready. On Wednesday 5, the Royal Ballet opened its 2022-2023 season by dedicating the performance to the memory of the late monarch – and then danced Kenneth MacMillan’s Mayerling (1978), a morbidly psychosexual and political study of royal troubles (including morphine addiction) that made the collected scandals of Margaret, Diana, Andrew, Harry, and Meghan seem small fry.

Mayerling, a richly absorbing yet obviously imperfect work that has opened several other seasons in the past, has been one of the company’s signature works since it was young. (Over the decades, it’s entered the repertories of companies from Houston to Warsaw. This season, it will be danced for the first time by the Paris Opera Ballet.) Its darkness – part of what makes it great – courageously extended everyone’s idea of ballet.

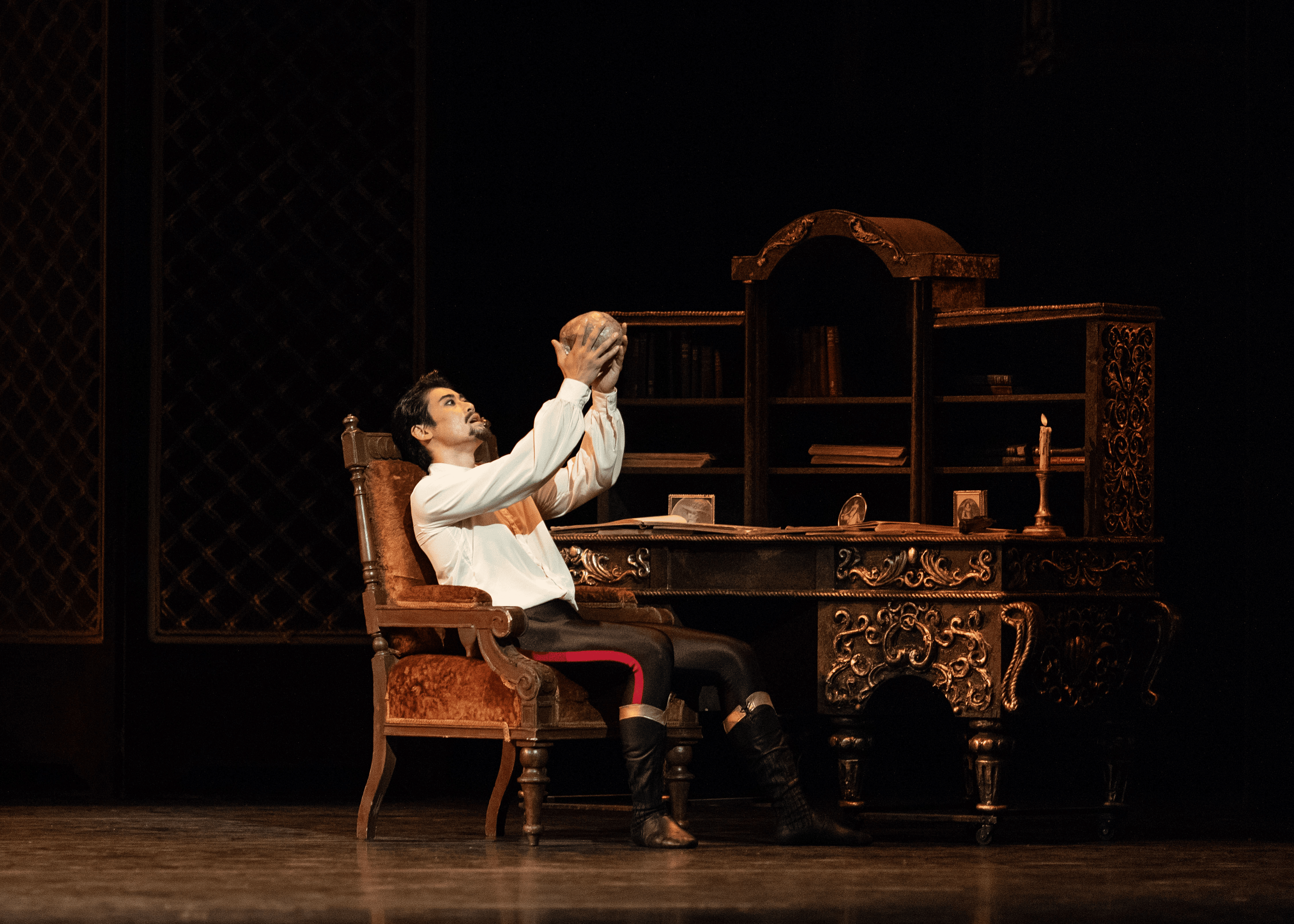

When it was new, the Royal Ballet fielded three casts; this season has five. Several women (Merle Park, Monica Mason, Alfreda Thorogood, Jennifer Penney among them) have danced two or three of its foremost roles; Genesia Rosato, Princess Louise at the 1978 premiere, went on to play no fewer than four other important Mayerling parts. Wednesday’s cast, led by Ryochi Hirano as Crown Prince Rudolf, featured two of today’s most prestigious international ballerinas, Marianela Nunez as Mitzi Caspar (the mistress to whom Rudolf first proposes the idea of a double suicide, but who betrays his idea to the Habsburg secret service) and Natalia Osipova as Mary Vetsera (the teenage mistress who joins him in both sex and death). Often today’s Royal Ballet feels like a hotel for international stars; in Mayerling, it’s a real company again.

MacMillan dedicated it to Frederick Ashton, his predecessor as the company’s artistic director and resident choreographer. Mayerling is to a score arranged from multiple Liszt compositions by John Lanchbery; Ashton had made six ballets to Liszt music and had often commissioned Lanchbery to arrange scores for him. Ashton, the ultimate chorographer laureate, was a friend of the Windsor royal family; MacMillan, one of the Angry Young Men generation since the 1950s, had already depicted the collapse of the Romanov dynasty (Anastasia, 1971) and the sexual escapades of our so-called Virgin Queen, Elizabeth I (Gloriana), before coming in Mayerling to the Habsburgs’ worst crisis.

All MacMillan’s three-act ballets – Romeo and Juliet (1965), Anastasia, Manon (1974), Mayerling, and The Prince of the Pagodas (1989) – start out by depicting formally admirable Ashton-type high-society worlds before charting the forces that will shatter them. Mayerling is the most original and imaginative of these, and yet it’s the one that best masters the many Ashtonian felicities with which it brings to life its varied and vivid social fabric. Ladies-in-waiting, chambermaids, officers, whores, royal mistresses and ex-mistresses, all are keenly characterised in dance terms, with delicious footwork and upper-body vigour.

The steps for the six chambermaids are irresistibly juicy, but there’s also a fleeting female quartet at the Hofburg Palace, led by Rudolf’s mother, the Empress Elisabeth, and his wife Stephanie, in which the royal women elegantly pivot before graciously hopping backwards, their lines and symmetries marvellously capturing the charming decorum of the Austrian upper crust. A fortune-telling episode for three women – Mary Vetsera, her mother Helene, and their scheming visitor Marie Larisch – is the most perfect and colourful scene ever made by MacMillan.

These piquant details become the frame for the sex, violence, and still breathtaking psychological need of the expressively acrobatic duets for Rudolf with, first, his terrified and conventional bride Stephanie and, ultimately, Mary Vetsera. MacMillan’s imaginative understanding of these private lives still astounds.

On Wednesday, several leading dancers – Hirano as Rudolf, Laura Morera as the machinating yet needy and compassionate Marie Larisch, Francesca Hayward as Stephanie – had fleeting moments when their movements lost psychological urgency, while Osipova, playing Mary with unhesitating intensity, had none of the occasional stillness that heightens this role. Some original flaws remain: he scenario says that, as Rudolf makes his way to his bridal night, the four Hungarian officers are talking politics to him, but it looks more as if they’re trying to blackmail him. MacMillan made too little of the moment when Mitzi betrays Rudolf. Even so, Mayerling stayed brilliantly alive. No other MacMillan ballet has its wealth of internal detail. You can lose yourself in the cross-currents of its relationships.

photo: ROH/Helen Maybanks

Comments