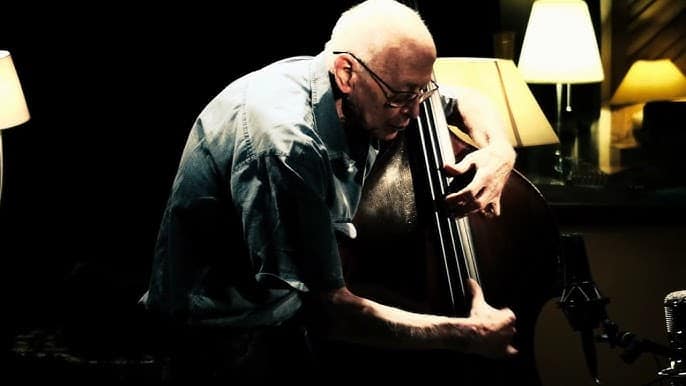

Death of an American heldentenor

RIPMessage from Frankfurt Opera:

The US opera singer William Cochran died on January 16, 2022 at the age of 78 at his home in Königstein im Taunus. This was announced by his close family. From the beginning of his international career, William Cochran performed as a Heldentenor in the most important opera houses of North and Central America as well as Europe and Asia.

After having won many of the most important singing competitions in the United States at the age of 24 – among others as the first co-winner of the Lauritz Melchior Heldentenor Foundation Grant – the student of Lotte Lehmann began his career in 1969 when he participated in the “New York Metropolitan Opera Auditions” and was awarded a contract by Sir Rudolf Bing to sing at the Metropolitan Opera as the “Young Heldentenor” even before the semi-finals of this competition.

Born in 1943, the tenor came to Europe in 1969, where he became a member of the ensemble of the Frankfurt Opera under Christoph von Dohnanyi and a regular member of the Bavarian State Opera in Munich. Regular engagements at the most important opera stages of the world followed (e.g.: Metropolitan Opera, San Francisco Opera, Covent Garden, Amsterdam, Opéra Nationale de Paris, La Monnaie Brussels, Zurich Opera House, Vienna State Opera, Berlin State Opera, Hamburg State Opera, and many more).

His repertoire comprised more than 60 operas, including all of Richard Wagner’s Heldentenor roles. In addition – and this was his artistic preference – character roles in contemporary operas. He also celebrated great success with the leading roles in Leos Janacek’s opera “Jenufa” and in Benjamin Britten’s operas. As “Peter Grimes” in Willy Decker’s production of the Brussels Opera he shone at the Teatro Real in Madrid in 1997.

For many years he appeared regularly at the Düsseldorf Oper am Rhein, for example in Schreker’s “Die Gezeichneten” (1987), but also in operettas by Jacques Offenbach, which suited his acting talent and sense of humor. The quality of acting in operatic performances was of great importance to William Cochran. This could be experienced impressively under Ruth Berghaus’ epic production of Wagner’s “Ring” cycle (1985-1987) in Frankfurt. “Technically, the education in Germany to become a singer is still excellent,” William Cochran told dpa in 2002, “but the charisma of the singer is the decisive factor for success. It comes down to the finishing touches.”

William Cochran became known through film, television and radio recordings as well as with numerous records, such as the first act from “Die Walküre” (Richard Wagner/EMI) under Otto Klemperer and “Doktor Faustus” (Ferruccio Busoni/DGG) with Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau under the direction of Ferdinand Leitner (This recording won the “Grand Prix du Disque” in 1971). William Cochran contributed to television and radio recordings with conductors such as Leonard Bernstein, Claudio Abbado, Richard Kubelik, Bernard Haitink, Wolfgang Sawallisch and many more as well…

His stage career ended abruptly in 2001 due to an accident that befell him on the eve of the premiere of the opera “Re in Ascolto” by Luciano Berio, whose main role he was to sing. He struggled with the consequences of the accident until the end.

After his active career, William Cochran dedicated himself to the musical education of young singers and the goal of introducing children to the specific art form of opera as early as possible in schools. Under the patronage of the Hessian Ministry of Education and Cultural Affairs and the Hessian Ministry of Science and the Arts, the project “Oper in die Schule!” reached some 10,000 students in elementary and secondary schools nationwide from 2004 to 2008. William Cochran’s work and the project with students from the Frankfurt University of Music and Performing Arts was awarded the INVENTIO sponsorship prize in 2004 by the acting Federal President Johannes Rau.

The Frankfurt Opera honored him on his 70th birthday with the words, “William Cochran’s scenic explosiveness, unmistakable vocal idiom, and the radiant penetrating power of his high-top notes sparked what in theater might be called a “magic moment.”

William Cochran leaves four children from his first marriage, eight grandchildren, and his partner and family.

Will the large presence of American singers in German opera houses continue, or are we seeing the end of an era? It’s little wonder that Cochran lived in Germany. The lack of work for opera singers in the USA makes it difficult for them to live there. They go to Europe as something like economic refugees. Germany has long been very generous to them.

In stands in contrast to the trillions of dollars the US has spent stationing troops in Germany since WWII. In the last ten years alone it has cost one billion. There are currently 35,000 US troops in Germany, down from up to half a million during the height of the cold war. The money spent has been tremendous economic boon for Germany.

https://www.iamexpat.de/expat-info/german-expat-news/germany-spent-almost-billion-euros-us-troops-past-10-years

And that’s the irony. The US has spent trillions presumably defending Germany, but American opera singers have to flee to Germany for work.

That heavy presence of American singers seems to be a thing of the past. There was a time, up to about 30 years ago, when it seemed as if the second tier – and below – of German houses was heavily staffed by American singers. More recently that role has been filled by singers from Eastern Europe, and, even Central Asia. I have often wondered why. Are fewer singers being turned out by American conservatories and universities? Or is the current generation less ambitious?

Quite simply, the Eastern and Central Asia singers are cheaper to employ. This is happening all over the world (and not just in opera).

And they are inferior to other European singers, especially German, English, Scandinavian and French.

Some of the Americans then (e.g. James King, Helen Donath and others) were clearly of the FIRST tier. In any event there is no question in re: the decline of US talent (as well as other places such as Italy) and the tremendous – often vastly over-exposed and over-promoted – surge of performers from Eastern Europe, especially in theatres like the Met.

There has been a significant increase in the number of Asian singers getting jobs, especially Koreans. Many study in Germany. They are thus well-informed about the system and expectations and thus have an advantage over Americans who didn’t study in Germany.

@ William Osborne: Korean singers don’t have much of a chance as soloists unless they’re mezzos or baritones. The sopranos and tenors have it much harder, with a few notable exceptions.

Amplifying the knowledgeable responses already posted by other contributors:

Singers have always been ambitious: it’s a highly competitive career. The competition they face now is not merely the sheer quantity of alumni turned out by the domestic training system – the contrary of «fewer singers being turned out» – but the market itself (even with the growth of regional opera companies that did not exist in the immediate postwar era, there’s only so much work to be had), the decreasing interest in – much less awareness of – the classical performing arts (which do not form part of the US school curriculum), & other entertainment options (e.g. the internet).

The German-speaking scene in the aftermath of WW2 could accommodate so many US singers because of conflating supply-&-demand. Germany & Austria regarded opera as a cultural imperative, providing a market (demand) that has never existed in the US, but they didn’t have the number of artists (supply) available to fill all openings – we’ll never know just how many talented artists were casualties to the war. Decades later, the Eastern world opens up – e.g. fall of communism, Asia becoming a economic superpower even in the Western world – & this opened up a supply of artists who previously could not have had such operatic opportunities. And frankly the lucky-chance stories that US singers of that postwar German/Austrian period lived would be impossible today: the application/audition/hiring process is much more stringent, specifically to weed out competitors in a crowded field.

Eastern European singers are cheaper.

In the past, the American singers have travelled to Europe simply because there were more opportunities to sing in Europe (especially Germany). As time has gone by, more opportunities have arisen for American singers to sing in their home country (with the advent of young artist programs). More Americans have been able to get their careers started at home rather than setting up home in a smaller German house and moving up over time. The large ensembles in many European houses have also become much smaller which has changed the outlook for singers heading over. Another note…great training goes on in the American Conservatories and universities. In fact, this is still the case. When an excellent teacher from the US comes over to teach while on sabbatical, they are often offered positions or encouraged o stay on the European side due to a lack of quality teachers. This has happened time and again. None of these folks have headed to Europe as economic refugees. It is now, as it has always been, about where the work is. It will always be that way.

Uh, leaving one’s country to find work is a central part of being an economic refugee. During the 13 years I lived in Munich, I also saw how much many of those singers hoping for jobs suffered from poverty and isolation. But what you say about excellent American vocal pedagogy is true.

It reflects the vastly different priorities of the two societies – one based on promoting and preserving great culture, the other on vast displays of militaristic imperialism in the service of powerful unaccountable corporate elites.

“…Trillions of dollars spent stationing troops in Germany since WWII.” You might check your arithmetic. But there is no irony here. Opera is culturally more important and opera houses more numerous in Germany than in the U.S.

So there’s no irony that the military budget ($750 billion) is 5000 times larger than the NEA’s ($150 million.) Indeed, it shows where American interests are….

It’s always nice to laud the career of a performer post mortem, but plumping up basic facts is no help.

As for Cochran having “regular engagements” at the Met, he debuted with 10 performances of “Die Meistersinger” in two months in 1969, but in the tiny role of Vogelgesang, not Walther. 16 years later he returned for two performances as Bacchus to the Ariadne of Jessye Norman, but the sum total of what Patrick J. Smith of Opera magazine had to say was that “Norman easily overmatched William Cochran’s worn but serviceable Bacchus.”

While he had a more substantial career at Wiener Staatsoper (58 performances between 1972 and 1989), his roles do not define the stuff of Heldentenors: Tamino, Lenski, Hoffmann, two Janáček heroes, and, after a 10 year absence, the Tambourmajor in “Wozzeck”. Yes: he did four performances each as Lohengrin and Bacchus, and seemed to be the go-to Erik in “Holländer” for four seasons, but these roles do not, for me, qualify him as a Heldentenor.

San Francisco presented him 12 times: once as Froh (“Das Rheingold”), five performances in the lesser role of Tichon in “Kát’t Kabanová” and six late-career (1997) outings as Herodes.

Coven Garden hosted him exactly once, in 1974, apparently as a replacement for Jon Vickers.

I think that’s enough research to conclude that his glory days were spent in Frankfurt and provincial houses in Germany.

Despite your efforts to denigrate Mr. Cochran’s career, he still had a more distinguished body of work than most singers.

RIP

It is true that Cochran during his long career flew mostly under the radar of record companies and major opera houses, but he was a cornerstone of the operas in Frankfurt and later Düsseldorf for many years and the very imporsonation of a house tenor who sang more or less everything, often in very interesting productions on the height of the Regietheateer movement. He sang Siegfried in both the 1987 Berghaus production of the Ring in Frankfurt, and in the Wernicke 90’s version in Brussels and Frankfurt. I heard him as Parsifal in Düsseldorf later, still in good voice. Here’s a sample of the NY Times review of this 1987 Siegfried:

“The most interesting of the singers of major roles was William Cochran, an American tenor, as Siegfried. Mr. Cochran is a longtime member of the Frankfurt company who has never had much of an international career. But as Siegfried he revealed a genuine baritonal, heroic tenor allied with excellent phrasing and diction and willing acting. He is a bulky man, but that didn’t hinder the careers of many notable Heldentenors of the past. And while his voice is neither inherently beautiful nor perfectly produced, he is certainly superior to many of the singers of this gargantuan part on more prominent stages today.”

Your fact checking may be 100% spot on. But the tone of your text, and the fact that you write anonymously (clever name), together with my singer‘s sensitivities, point very strongly to either sour grapes, or you knew William Cochran and had a beef with him. There‘s nothing wrong with correcting information if you know better, but it can be done with grace and kindness.