The opera lover and the hedgehog

mainIn this weekend’s Wall Street Journal I write about the relationship between two philosophers, Hannah Arendt and Isaiah Berlin.

It was hate at first sight. And then it got worse.

Here’s the intro:

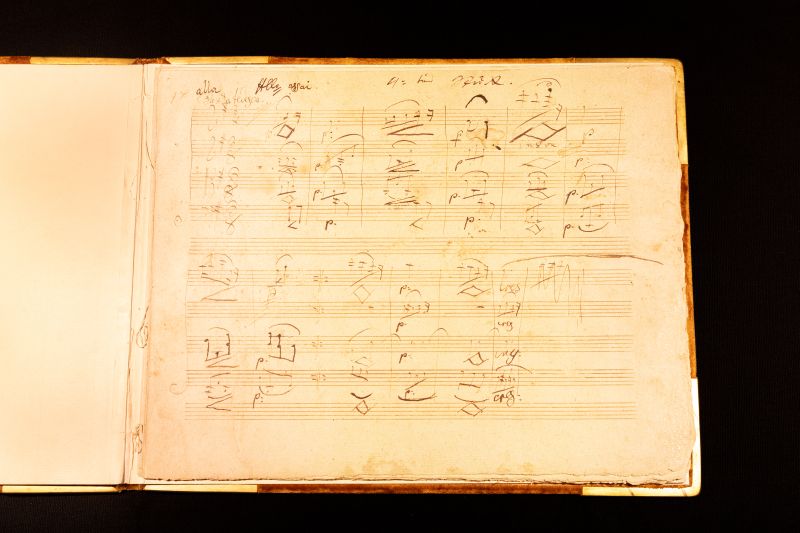

In the halcyon age before Covid, I caught a flight to a small town in Germany to see an opera about love between two philosophers. The love was not in the least bit Platonic. Hannah Arendt was 18 years old, fatherless, a virgin. Martin Heidegger was in his mid-30s, married with two sons, a leader in his field. In modern terms, the liaison was a classic #MeToo scenario, an abuse of trust and duty.

In real life, Arendt was in denial, and Heidegger drew a line between life and mind. He would tell his students: “Aristotle was born, worked and died, now let’s turn to his ideas.” Ella Milch- Sheriff’s opera, “The Banality of Love,” projected something of his view that an individual human being is uninteresting. But in this case and many others, the ideas are shaped by the all-too-human flaws of the lives that conceived them—the two sides are inseparable. It is surely time to reassess Arendt, a major philosopher of totalitarianism, in light of her formative philosophical influence, a brilliant chameleon who would transform himself into an intellectual apologist for Nazism.

Now read on here.

I was taught music history in the ‘70s and early ‘80s with a similarly blinkered approach, rendering a fascinating subject completely sterile and hopelessly boring. I hope things have improved.

Love to read on. Can’t. Paywalled. And I guess you can’t c&p because it is their property.

The article is behind a paywall.

Hannah Arendt was a great philosopher, with an excellent explanation of totalitarism and her ideas remain topical as we can see all around us – the threat of totalitarian ideology is a structural flaw of human societies and has always to be kept in check.

Heidegger I never found very interesting and his meandering about ‘being’ and ‘time’, if you really think it through, nonsensical: projections of non-existent problems which seem deep but have no substance. Heidegger did not like modernity, in which he was not alone and in which he was right – but that does not mean that for that reason, nazism would be better. It is a matter of gradation of insanity.

I would really like to read the article, as I wonder at “apologist for Nazism.” I remember reading the Eichmann articles in the New Yorker when I was a student, and a few years later again after I saw the movie about her.

I vaguely recall that she had some issues with the conduct of the trial, and that a lot of leaders in various Jewish communities took umbrage. And of course everyone knows about “the banality of evil,” which I think is a chilling and apposite condemnation — I never saw it as defensive. It suggests that any one of us can be culpable in evil, not just maniacs.

So I would be very intrigued to know your argument, though not to the extent of subscribing to the WSJ.