One composer who cannot be decolonised

Comment Of The DayA response from Professor Robert Eshbach to the gathering storm of academic wokeism:

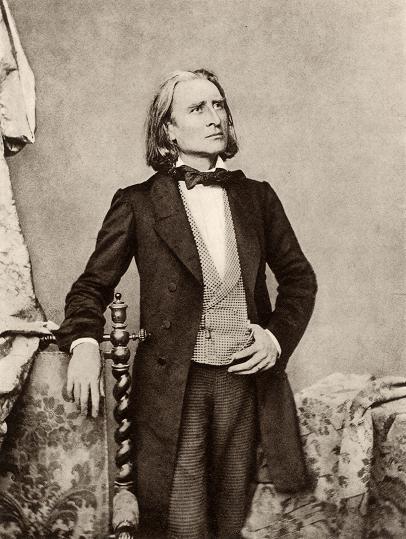

Who among the debunkers and ‘decolonisers’ of 19th-century music would dare to try to hold their own in a conversation with Franz Liszt—to accuse him to his face of a narrow, monolithic viewpoint? A man who spent his childhood in multi-ethnic Hungary, among Magyars and magnates, Turks, Slavs, Gypsies, Catholics and Jews—who traveled from St. Petersburg to Constantinople, from Paris and London to Weimar and Rome? The languages he spoke, the books he read (and wrote), his knowledge of art, his comprehensive understanding of music, historical and contemporary, and his unparalleled ability to perform it. The people he met, from tsars and sultans and kings to peasants and beggars—the writers, the painters, the philosophers, composers and virtuosi, the politicians and generals and priests in whose circles he shone… A charismatic “rockstar” named after St. Francis, with a spiritual life that led him to take the minor orders of the Catholic Church… A transformative genius who began his life on the Esterházy sheep farms and grew up to live with a princess—who, even in old age, continued to travel 4,000 miles a year by coach and train and steamship. A world-renowned teacher and a generous philanthropist. A critic of musical conservatism and a champion of Wagner. A pathbreaking futurist composer who, as a national hero also wrote Hungarian music in traditional forms. An artist of immense influence on those who studied with him, those who quarreled with him, and those who followed him.

Oh, no… he knew nothing about humanity—and he has nothing to teach us.

Comments