Comment of the Day: The Mann who knew his place

Album Of The WeekFrom a pseudonyous comment to our Album of the Week:

Golo Mann deserves indeed a fairer assessment. (I met him several times during the last two decades of his life.) He was discreet and withdrawn, but no enigma, not even to himself. He self-diagnosed during the first years of emigration:

“Golo Mann was born as a ,son‘; did not like it; could not help it.“

The oppressive personalities of his parents, the inferiority complex towards his brother Klaus, a general sense of inadequacy despite his great talents, compounded by a lifelong difficulty in coming to terms with the fact of being gay, all this made him a hurt, vulnerable, somewhat tortured man. But he was not “embittered”, let alone generally so. He was a skeptic, and more often than not a pessimist, in an era when history had a knack of making even pessimists appear as lighthearted fools.

Also, as anyone who interviewed him for radio or television would, I think, concur, he was a hard case to steal a sound-bite from. His eloquence and erudition were impeccable; but his carefully convoluted periods, formatted in paragraphs, complete with mental footnotes and references, were drafted for the printed page, not for the fleeting instantaneity of audiovisual media. Golo Mann was, essentially, a “Gelehrter” of the XIXth century mercilessly thrown into the mid-XXth.

I concur very much with Norman Lebrecht. Whether or not Golo was “embittered” is to my mind a matter of definition. I would say that in part he was, but not totally. He did write that any intelligent and sensitive person who had witnessed the period of the Third Reich could never again experience unclouded happiness. My recently published e-book “Fände einer nach vielen Jahren…: Erlebnisse auf den Spuren von Klaus Mann” contains a whole chapter concerning my encounters with Golo Mann. He was always very fair and cooperative towards me as his brother Klaus’ biographer – with the exception that in 1977, he maintained the secret still kept by the entire family that Klaus Mann’s diaries actually existed. They didn’t start to appear until 1989.

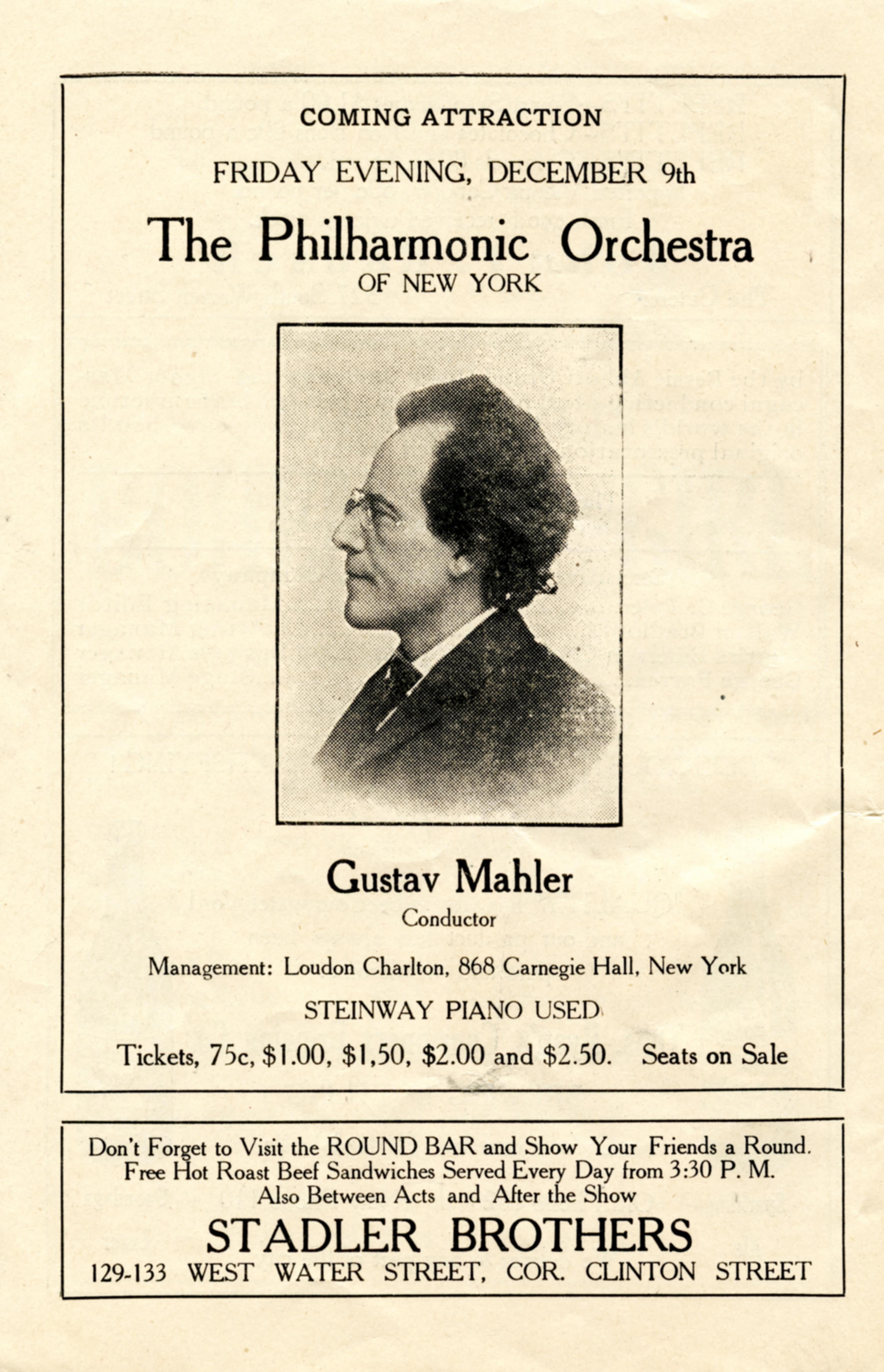

I am very anxious to hear the recordings of Michael Mann playing the viola. It is little known that Michael was the only member of the Mann family who attended Klaus Mann’s funeral after his suicide in Cannes on May 21, 1949. Michael Mann arrived late at the funeral – the coffin with Klaus Mann’s remains had already been lowered into the grave, but had not yet been covered with the earth. Several witnesses have testified that Michael Mann did not speak, but very fervently played his viola (without accompaniment, of course) at his brother’s graveside. I don’t remember who said that he played “a Largo by Benedetto Marcello;” I searched for this piece in vain for years. Several people thought that it was just a piece that Michael Mann had in his repertoire at the moment and had nothing to do with Klaus. It turns out that the designation “Largo” was probably misleading: an Adagio from an Oboe Concerto in D Minor is one of Marcello’s best-known works, and I can only conclude that it was this Adagio that Michael Mann played at Klaus Mann’s graveside as a final farewell before the earth was shoveled over the coffin: https://youtu.be/mgYZJSzUrrg. I find this Adagio by Marcello in fact one of the saddest and most beautiful musical statements from the entire Baroque epoch – the equally lovely and better-known Adagio by Albinoni is said to be not entirely authentic.

Now this is what I call a ‘divine surprise’: Having Fredric Kroll commenting on my casual remarks, which Mr. Lebrecht kindly thought worth highlighting (although I suspect he still disagrees with them).

This is all the more touching because, in one of my first encounters with Golo Mann, I had, in my youthful naiveté, thought nothing of interrogating him head-on about Klaus. Granted, yours truly was emerging from a seminar on the subject of “Der Wendepunkt”, and we had a duty towards literary history, hadn’t we, but still. What I got from Golo (not that I ever dared addressing him thus) was an object lesson, nay , a masterclass in evasive action. I thought I had been immersed in his comprehensive panorama of wartime life in émigré (refugee, more properly) intellectual circles; which I may well have been. But on the precise subject of my inquiry, Klaus Mann, I knew less when we were done than when I had started.

This was of course more than a decade before the diaries were ventilated, let alone published.

Anyone interested in Klaus Mann, in the Mann family in general, or just in the fine art of intellectual biography, owes Fredric Kroll a debt of unbounded gratitude.

Mr. Kroll: Is your book translated into English or French? I greatly look forward to reading it. I ran into an Austrian German teacher here in Paris that had written, or was writing a thesis on Klaus Mann. I hear Golo be came very right-wing at the end of his life. Is that true?

More welcome information about Thomas Mann’s sons. Benedetto Marcello’s beautiful Adagio exists in an exquisite transcription for piano recorded by Edwin Fischer, who I think adds a four-note moving bass line at the end. This transcription is credited to J. S. Bach. Fischer’s student Alfred Brendel also recorded it, but without the addition. T The original version for oboe can be heard from Leon Goosens. There is no finer eulogy.

The persistence of surnames is noticeable in Manniana. His elder brother Heinrich married Nellie Kroeger, as in Thomas’s novella “Tonio Kroeger”. There is a pastor Pringsheim in “Buddenbrooks”, that being Katia Mann’s maiden name, and Mr. Kroll recalls “Felix Krull”, another novella.

Family tensions were already there. Thomas’s mother was Brazilian. His sister, an unsuccessful actress, had taken her own life.

It is certainly true that Golo Mann had the family demons on his shoulder and that he was in many ways not exactly happy. But that should not disguise the fact that he was wildly successful in his own right, and not just as a “son”.

He was a sought after professor and public commentator, an advisor to high ranking politicians, and some of his books enjoyed an enormous circulation: his “Deutsche Geschichte” (translated into many languages), his “Wallenstein” biography, his “Propyläen History of the World”.

I realize that that doesn’t stop anyone from being less than happy. But it is also safe to say that his professional success would have been more than enough for most people.

Carl Gustav Jung: “I have yet to find a patient who thinks his parents did right by him.”

There have been found two parents, a man and a woman, in the south of France in the fifties of the last century, who had three children who freely declared their parents did very well. A book has been written about the case by psychiatrist Dr Albert Sauvage: ‘Le grand miracle de l’amour: secret encapsulé dans l’ombre de l’inconnu’, 1958, Editions Fugitives, Paris.

Åh, but were they patients of Dr. Jung, John? That is the operative word.

The Mann sons were more interesting writers than the father.

Evan: I wouldn’t go that far, but they were interesting in their own right. I can’t think of anybody more different from the patrician Thomas Mann than the bohemian Klaus Mann. Once again, let us not forget the brilliant Erica. Thomas Mann also had daughters. The book of short stories I have read by Erica-all of which take place in Nazi Germany-is brilliant and profound.

Reading Thomas Mann is a very slow process since every detail is carefully worked-out to prevent the reader from missing little bits that later-on in the book may have some significance. His son Klaus however, took great speed to get to the other cover; he belonged to the 20th century while his father was really a 19C one.

Thomas Mann used Leitmotif literary devices and wrote his short-story “Tonio Kroeger” in sonata-allegro form.