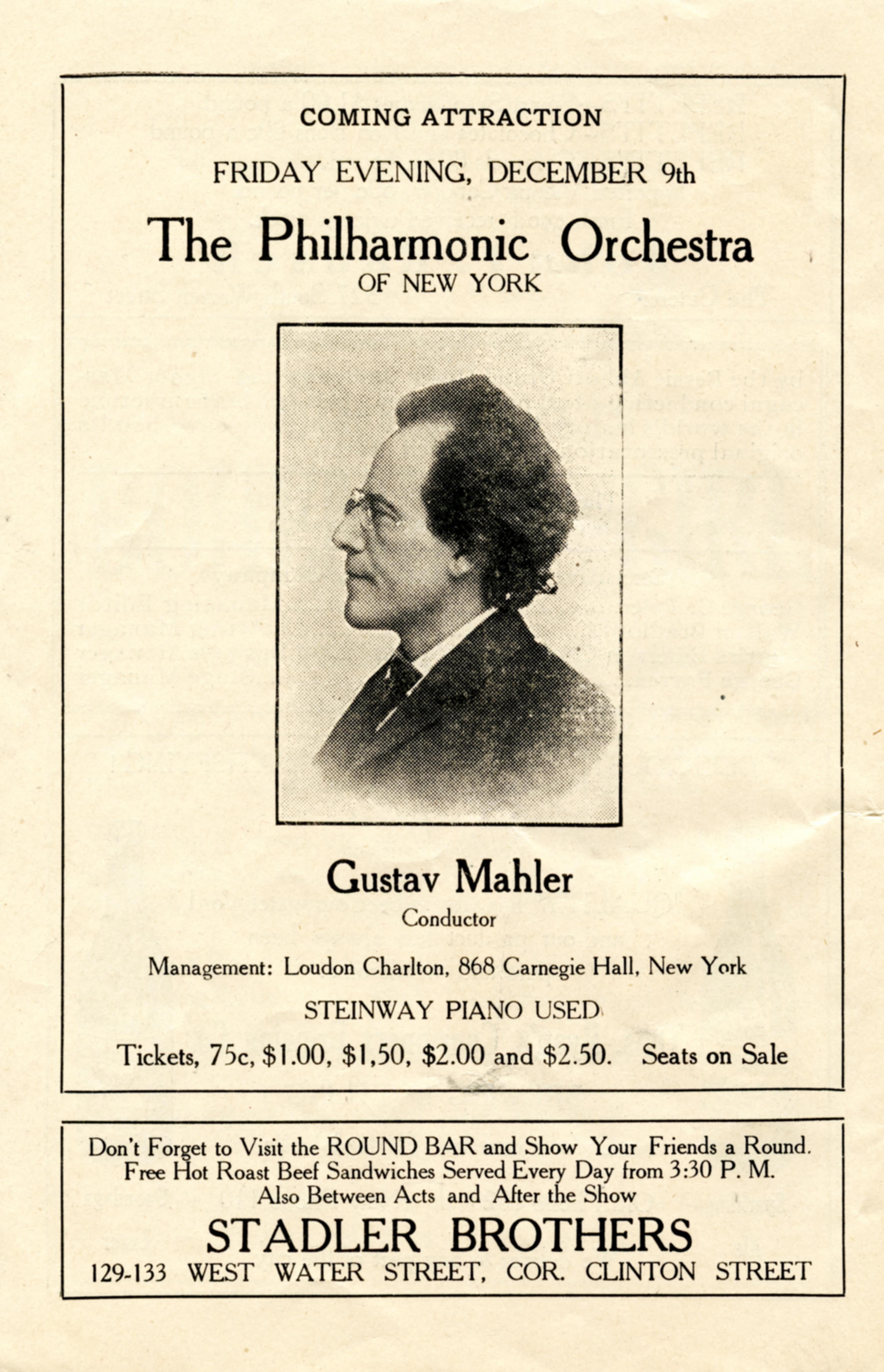

Germans rewriting history (1): Mahler

aboutFrom a speech by the Federal Culture Minister Monika Grütters: ‘Sudeten German artists have written history in many ways, which is an integral part of our educational canon: in music with Gustav Mahler, in literature with Rainer Maria Rilke, and in the film Oskar Schindler is immortalized, who saved 1,200 Jews from the National Socialist terror regime.’

How wrong is that?

Mahler was not Sudeten. He was born on the Bohemia-Moravia borders to a Jewish family, citizens of Austria-Hungary. To depict him as ethnically Sudeten and a symbol of German unity is a particularly ugly distortion in light of what Sudeten Germans symbolised.

Gustav Mahler‘s mother tongue was German. And in this sense he came from that part of Bohemian/Moravian society which had that cultural background. Wether it is a good idea to call this Sudeten is a different matter.

How about someone shows the common decency of asking the Bohemian/Moravians what they think about this.

Do they accept Mahler as one of their own or not?

I say any further discussion of this topic on SD is in gross violation of Bohemian/Moravian sovereignty.

The South Moravian Liberation (SML) Front disagrees. So does the Liberation Front of South Moravia (LFSM).

What about the BSM (Bond against the Suppression of Moravians) and the SPMCI (Society for the Preservation of Moravian Cultural Identity)? Not to speak of the MVV (Moravians Vorwärts Verein).

Not that “Bohemian/Moravian sovereignty” matters much in the grand scheme of things.

More important is the question: was Mahler a German composer? In a cultural sense, yes, he was. Was the Austrian-Hungarian Empire a German nation? Yes, in a cultural sense: it belonged to the Holy Roman Empire. Did Mahler write in the German classical tradition? Yes. Did he represent the humanist side of German culture? Yes. Was he a Jew? Yes, which puffickly fits within the cultural context of humanist Germany.

An interesting aspect in this respect are the texts which inspired him and which he set to music. The 8th Symphony comes to mind, with its second part (Faust!). Or also Des Knabens Wunderhorn. Culturally, there is a strong link between Mahler’s music and German(speaking) culture.

I think that normaly Mahler should be in relationship with Czech Republic like Dvořák or Smetana. he was born in the middle of the Czech Republic of today. But I don’t see any strong link with Germany. he made his profesional carreer in Austria mainly where his music was not beloved (I made the trip to Grinzing it’s very difficult to find the grave there’s nothing about Mahler in town and it was a very bad surprise for me about Vienna) and he didn’t stay a long time in Amsterdam where his music was understood for the first time.

You must have missed the Gustav Mahler Saal and Rodin’s sculpture at the Staatsoper. Just right across the Staatsoper is the Mahlerstrasse (it had a different name only from 1938-45). And you have obviously not yet seen the memorial plaques at the former hospital where Mahler has died or at the apartment complex in Auenbruggergasse where he he lived with Alma.

I know the sculpture inside the opera house, I saw it on a documentary. But there isn’t much on the streets about Mahler in Vienna. That’s a fact. Bruckner has a big memorial same thing for Beethoven…And I don’t talk about the difficulties to find the last home of Mahler in Grinzing… It’s almost a shame.

While Mahler took great interest in Smetana’s operas and wacky tone poems, he conducted surprisingly little Dvorak. He eventually did conduct “The Wood Dove” (or “Wild Dove”) and “A Hero’s Song”, Op. 111 – both late orchestral tone poems from Dvorak.

Mahler grew up speaking German and, like his father, read German literature. What Russian literature he read – principally Dostoevsky – would have been translated into German. This is not to say that Mahler didn’t have strong feelings for his native Bohemian/Moravian soil – he did! However, Iglau – now Jihlava – was a garrison town for the ‘mighty’ Austro-Hungarian Army, being that it was situated roughly half-way between Wien and Prague. With the exception of Budapest, all the conducting posts that Mahler had in his gradual rise to stardom, were with theaters where German was the principal language. In those days, many ‘foreign’ operas were sung in German. Even Mahler’s brief post in Prague was at a German theater. It was from hearing the garrison band on a daily basis in Iglau, that Mahler developed his love for marches and ‘marshal’ music in general. As a young man, he became a Wagner disciple as a matter of course, even taking the obligatory pilgrimage to Bayreuth. The fact that Mahler would later have a nasty adversary by name of Cosima Wagner, did not diminish his enthusiasm and expertise in all things Wagner. Even though the young Toscanini was a competitor who took Wagner away from Mahler at the N.Y. Metropolitan Opera, Mahler continued to conduct Wagner excerpts with his N.Y. Phil. He was ALWAYS highly lauded for his Wagner.

As a composer, it would be fair to say that Mahler’s influences were more cosmopolitan in a a pan-European sense. As well as being inspired by Haydn, Beethoven Schumann and Wagner (with a tinge of Lehar, here and there), Mahler was clearly familiar with Verdi, Berlioz, Smetana, (some) Dvorak and Tchaikovsky. As a conductor, Tchaikovsky’s “Eugene Onegin” was one of his specialties, as was “The Bartered Bride” (Smetana). Mahler even conducted Tchaikovsky’s “Manfred” Symphony on two different occasions (a truly proto-Mahler work, if there ever was one). A bit of Richard Strauss rubbed off Mahler too, here and there as well. Mahler badly wanted to give the world premiere of “Salome” (the Austrian censors wouldn’t permit it), and loved hearing a performance of “Don Quixote” someplace in Germany.

In Mahler’s last two seasons with the N.Y. Phil., he became even more cosmopolitan and ‘catholic’ in his music programming. While he didn’t ‘get on’ with Rachmaninoff on a personal level, Mahler recognized that Rachmaninoff had come up with a truly masterful concerto, when he accompanied Rachy in the American debut of his 3rd Piano Concerto. So much so, in fact, that Mahler had his orchestra start all over again at the end of the rehearsal. Not one player protested against this. It was even rumored that Mahler was carrying a score to Ives’ 3rd Symphony at the time of his (Mahler’s) death.

The problem in assessing Mahler the man, as well as his accomplishments, is that we’re looking at Mahler through a rear view mirror. While we don’t want to downplay what transpired in Europe in the following decades, it’s easy to forget that Mahler lived in that elevated, rarefied time before the great European tragedy kicked in. Yes, there were warning signs all over the place. Personally, I truly believe that that’s what Mahler’s tragic A-minor symphony is all about (and not about his own personal insecurities and superstitions). But that’s another story. Pan-German feelings were on the rise within the Austro-Hungarian empire, as were strong desires for independence among the many minorities in the Hapsburg Empire as well. Along with all that, Theodore Herzl realized the dangers of the ever growing antisemitism in Vienna, and founded his Zionist movement as a solution. Yet, when World War I commenced, many Jews fought with the Austrian and German Wehrmacht, viewing themselves as Germans, first and foremost (Mahler died three years prior). Tragic, yes, but that’s the way it was. Few people would have predicted the insanity and degradation that followed in the 1930’s and ’40s. We can argue for all eternity, just how much Wagner was responsible for all that (I believe in making the actual criminals be responsible). Be that as it may, Mahler grew up in a time when aspiring to the great German culture – with Vienna being his eventual cultural target – was much like how Frank Zappa viewed coming to Hollywood, after having spent nearly his entire early life in the ‘inland valley’ region. Each corresponding city – Vienna for Mahler and Hollywood for Zappa – was the perceived zenith in both of their minds.

I often wonder: what if Mahler had lived longer and met the northern Moravian composer who came up with an entirely different solution, Leos Janacek. He certainly would have viewed him as the true successor to Smetana (and Mahler would have become far more familiar with Dvorak’s output as well).

And then there is the Finno Ugric Jean Sibelius who Mahler once met in Helsinki where he conducted…Beethoven and Wagner (what else?).

It is reported that Mahler eventually spent more time with painter Akseli Gallen-Kallela (Axel Waldemar Gallén).

https://www.br-klassik.de/themen/klassik-entdecken/was-heute-geschah-10291907-mahler-trifft-sibelius-in-helsinki-100.html

Yes Gallen-Kallela (my favorit painter i have to say) met Mahler for a portait fantastic like the “En saga” one for Sibelius. But he didn’t met him a long time. it was a short enconter between two genius

I generally agree, but your history is a little mixed up. The Holy Roman Empire, long an irrelevance, was dissolved in 1806. After the congress of Vienna in 1815, the lands ruled by the Habsburgs were named the Austrian Empire. After Austria’s defeat at the hands of Prussia in 1866, internal strife led to reevaluate the role of Hungary and to cut the Empire in two equal parts : the Empire of Austria and the Kingdom of Hungary, under one monarch, with a common foreign policy, but different parliaments, judicial systems, etc. Moravia fell into the Austrian part. From that moment on, everything in the Empire was “Imperial and Royal”, or Kaiserlich und Königlich, hence the omnipresent KuK.

So Mahler was born an Austrian subject, and remained so after 1867.

But the A-H Empire cannot be called a german nation, it was much more complex. It was a multinational state, with a strong germanic component, but which was only a small plurality : in 1910, german speakers were 23 % of the population, hungarian speakers 19,5%, czech 12,5, polish 9,7 %, serbo-croatian 8,5 %, etc.

Correct. But that does not diminish Mahler’s cultural identity…. he belongs to the German-European musical tradition, like Dvorak and Smetana.

Thanks for your great comment and your insight, I must have overlooked it before writing my own post.

Well said, and the right reply to those, who always want to divide, rather than humanely unite.

Mahler lived in German from August 1886 – May 1888 (Leipzig) and From March 1891 – April 1897, about 7.5 years of his 51. Despite the fact that there is a common language between Germany and Austria, don’t ever call an Austrian a German, or vice, versa, or you will elicit a response you don’t want. Mahler’s music was generally inspired from sounds he heard in his youth in Moravia and as an adult in the woods around his home in the Salzkammergut. I would not call him a German composer. With the exception of his years in America, 1908-1911, most of his life unless touring was spent in Bohemia, Austria and Hungary. Would you call Franz Schubert a German composer?

It’s the language which is the strongest cultural influence, and for composers the musical vocabulary and style. And identities are often mixed. Both Schubert and Beethoven shared a wider German cultural identity and the differences are of less importance. Beethoven and Brahms and Mahler lived in Vienna, which was a multiculti metropolis. Beethoven’s ‘heroic style’ derives from the French revolutionary brass band music, Brahms had his many Beethovenian and Schubertian moments, like Mahler who also flirted with Berlioz and Tchaikovsky. It is all part of the European picture, where differences are far less important than the similarities.

Beethoven was born in Bonn where he spent his first 12 years and lived in Vienna by choice. He has always been labelled a German composer. Brahms was born in Germany, Hamburg to be precise and did not move to Vienna, Austria also by choice until he was an adult. He is also labelled a German composer. Mozart, Haydn, Schubert , the Strauss family, Bruckner, Mahler etc. were all born in Austria, or Austria-Hungary, or for that matter, earlier than 1806, the Holy Roman Empire and have never been labelled German composers. The spoken language is not the musical language and none would consider themselves German composers, nor do the vast array of musicologists who study them consider the Austrian composers German composers. They are distinctly unto themselves. The French speaking Belgian composers conversely would be insulted if you called them French composers and vice versa, though there is some commonality between the two. The Americans and Brits, same thing. The one interesting thing is Franz Schreker and Schoenberg took their new musical theories to Germany for awhile and some of their disciples went there. The German critics and the public by and large rejected the Austrians even before 1933. After the War, however, many German composers did adopt the teachings of the Austrian composers. You wouldn’t however, call those composers Austrian.

All true but wouldn’t that be the accents of the small differences? Aren’t the similarities and the bigger cultural picture much more important?

And what to make of César Franck *(French? Belgian?), or Frederick Delius (British, German or American)? I find this labelling and hairsplitting about nationalities extremely smallminded and non-musical. It is the music that counts. All of these composers form the wider context of Western classical music.

And then, how would we consider the influx from outside Europe, like American/Chinese composer Bright Sheng? He certainly also belongs to the same Western context, simply because of the music, which often uses Chinese material but transformed into a Western language. Etc. etc…..

MET writes:

“Despite the fact that there is a common language between Germany and Austria…”

Sigh…this division is really a result of World War 2. Before then most German speaking Austrians would have thought of themselves as Germans, and being Austrian would have been a bit like being Bavarian or some other regional identity.

However, Bohemia, up until the First World War was largely bilingual; most people would have spoken both Czech and German, with German mostly used for higher education and in government and Czech a bit more common in the home (educated people would have largely spoken German). The nationalist movement tried to insist on people choosing which they were, but choosing was largely an urban phenomenom. The urban centres became increasing more Czech during the 19th century.

After WW1, only the Sedetan Germans retained a German speaking identity with the rest of Bohemia rapidly becoming mono-lingual and there was a process of Czechification.

Mahler was, of course, Jewish. There was a lot of debate before WW1 about whether the Jews should be included amongst “the Germans” in Austria-Hungary. Loosely, it isn’t wrong to call him “German”. He certainly should not be thought of as Czech or as “Austrian”.

Sorry, this is historically wrong. The Austro-Hungarian Empire did not belong to the Holy Roman Empire, simply because the Holy Roman Empire had ended in 1806. The Austro-Hungarian Empire was founded in 1867, before that there was the Austrian Empire founded in 1804. The Austro-Hungarian Empire was by no means German, it was multicultural and multiethnic. The head of state was the Austrian Emperor and the Hungarian King (in fact the same person who btw was also King of Bohemia). The Holy Roman Empire was never a state nor a nation, it was a political block of several European nations/states (some of them even fought wars against each other), of course it was never German but actually European.

It was a European ‘block’ with a certain cultural identity defined by language and traditions.

The Austro-Hungarian empire certainly was not defined by language. That is clearly wrong.

The only things culturally unifying the state were the Catholic church and the ruling royal family.

The question may be more important to YOU. Gustav Mahler was an Austrian composer and came from a Jewish family. Without a doubt, Mahler was of Jewish and German culture also linguistically. He was friends with the composers Arnold Schönberg, Alexander von Zemlinsky and Alban Berg, who admired his music. But he was NOT a Sudeten German, as Federal Culture Minister Monika Grütters stated in the opening address of the new Sudeten German Museum in Munich last October.

In precise linguistic usage, “Sudeten Germans” are only used to refer to those former Czechoslovak citizens who have committed themselves to the Sudeten German national movement and who profess it today, be it through their active participation in the social, political and cultural life of this movement, or through their active support for it political representation (1933-1935 Sudeten German Home Front, 1935-1938 Sudeten German Party, 1938-1945 NSDAP and after the Second World War the Sudeten German Landsmannschaft). I don’t want to see Gustav Mahler or my grandfather, the composer Hans Winterberg, there. They don’t belong there! My excitement comes from my Jewish grandfather Hans Winterberg’s denial in 2000/02. As a signatory to a contract, the Sudeten German Music Institute in Regensburg (Upper Palatinate District of the Free State of Bavaria) contributed to the fact that Winterberg was only allowed to be called a Sudeten German composer until 2015 and was never allowed to be called a Jew or of Jewish origin. To this day the original notes are “locked away” in the Sudeten German Music Institute!

To crown it all, Mahler converted to Catholicism in February 1897 and was possibly a lifelong agnostic.

He was probably influenced more profoundly by Schopenhauer, Nietzsche and Richard Wagner than by any spiritual-religious dogma.

How wrong is that?

Quite wrong. He was never agnostic. See inscriptions on symphs 9 and 10

Almschi?

You usually stop being agnostic when you are about to die.

As El-P so eloquently put it:

“There are no atheists in the fox-holes”

Except there are atheists in foxholes (that is an old saw which has long passed it’s time.) The fact is that there are many atheists in foxholes who are asking, even as the bombs fall around them where is “God”? Nowhere to be found, that’s where!

Mahler projects the words of Jesus Christ upon his own self-pitiful state which was caused by Alma running off with love-letter engineer Gropius.

„Mein Gott, mein Gott, warum hast du mich verlassen?“ (Mk 15,34 EU; Mt 27,46 EU; Psalm 22,2 EU)

Using these words in the context of a secular symphony is more a testimony of Mahler’s excessive self-pity than of unselfish devotion towards whatever god.

The godforsaken Mahler would only live and die for that one-and-only goddess, for Almschi.

It was Bruckner who managed to build the bridge between true religious faith and the symphonic format.

“Dem lieben Gott”…

“You usually stop being agnostic when you are about to die.”

You become diagnostic.

. . . just as long as you don’t become Dianetic.

Indeed. There is a difference between religion and spirituality.

I think we need to be more exact on this topic. What agnostic or atheist hasn’t, from time to time, used “my god!” as an exclamation? I think such usage is hardly proof of a personal conversion. The man who has come up with the most thorough, single volume biography on Mahler, Jens Malte Fischer, dedicates an entire chapter to this issue. I strongly recommend it.

While Mahler was highly self disciplined throughout his working years, he was very much a day dreamer in his youth. As such, god’s strict laws that are the basis of orthodox Judaism hardly appealed to him. And while Mahler was attracted to the trappings of the Catholic Church – cathedrals, stained glass windows, incense, chants, etc. – he could not and would not abide by the accompanying dogma. Yes, Mahler did convert to Catholicism. But as many of us already know, Mahler did so in order to get around Cosima Wagner’s objections and be better positioned to land his much desired Vienna Royal Opera gig. What then, was Mahler’s actual religion, if any?

Mahler and other artists and intellectuals within his circle, more or less invented a pseudo religion that worked for them. The god of this man-made religion (as they all are!), was nothing other than man’s own driven creative spirit. Hence, “Veni, Creator Spiritus”. From there, this quasi-religion got more complicated (as they all eventually do!).

In Mahler’s view of the universal order, man acquired cosmic brownie points – or good karma – by driving his/her own creative spirit as far as possible, while here on Earth as a mortal (and I presume this applied more to males than females). To waste one’s creative urge was, more or less, a type of sin. This is where their ‘religion’ makes an elliptical pass at Buddhism, as they believed that acquiring good karma points for one’s creative output in the here and now, made their ‘going’ easier in the next cosmic phase, or ‘reincarnated’ life cycle. Whether this whole process was overseen by an all knowing, ever wise, floating father figure was never clearly defined. I believe that that was the dead end that they were trying to avoid. It’s a type of thinking that’s sort of an early cousin to more modern ideas, where some believe the living universe is monitored by some impartial computer at its edge, or as a hologram that constantly keeps churning on itself.

Be that as it may (or may not), we can only speculate whether Mahler got caught up in the projected, “no atheists in a foxhole” syndrome. There’s no evidence that Mahler asked that a Bible or Talmud – or anything else – be kept by his bedside. If anything, he kept referring back to Dostoevsky, Jean Paul (Richter) and de Cervantes (“Don Quixote”). Perhaps Mahler’s religion could best be summed up by an old standing joke among musicians – one that has probably been around for centuries. When the usual “what is your religious belief?” question goes around the room, the musician will answer quite simply, “I am a musician!”.

I also wonder what is meant by “what the Sudeten Germans symbolize”. Can a certain group symbolize something – and if yes, what did or do the Sudeten symbolize?

The Sudeten Germans symbolise people who are victim to some mad tyrants elsewhere.

They symbolized the Sudeten symbol.

There is no rewriting of German history at all. Moravia always was part of Sudentenland:

The Sudetenland (/suːˈdeɪtənlænd/ (About this soundlisten); German: [zuˈdeːtn̩ˌlant]; Czech and Slovak: Sudety; Polish: Kraj Sudetów) is the historical German name for the northern, southern, and western areas of former Czechoslovakia which were inhabited primarily by Sudeten Germans. These German speakers had predominated in the border districts of Bohemia, Moravia, and Czech Silesia from the time of the Austrian Empire.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sudetenland

Quite absurd that a Culture Minister should have such vague historical insights. If Monika Grütters is so keen to mention an artist of Jewish heritage why not the obvious choice; Franz Kafka, now as she mentions Rainer Maria Rilke who like Kafka was also born in Prague, and as such not the arch typical “Sudetendeutscher” of the border region towards Germany ?

Perhaps the German state administration ought to set up a test for examining the historical knowlegde of their future Culture Ministers to avoid further embarrasment.

There is a silent rule in the Bundestag that the less politicians know about history the better, to prevent the development of sympathy for the darker corners of the past. Meanwhile, the humanist and philosophical and scientific and musical and classicist past is underestimated.

Interesting discussion amongst some very learned folks. I’ve always thought of Mahler as a “German” composer, in the broad sense of that word. When I listen to Mahler I hear Brahms, Bruckner, some Schumann. But what do I know? My PhD dissertation was on Vincent Persichetti (NOT an Italian composer 🙂

So let’s put this in an American context. Let’s say I’m a composer (instead of a music teacher). I was born in Tennessee but I’ve lived in North Carolina for as long as I’ve lived in TN (specifically EAST TN, which is WAY different than Memphis). So am I a Tennessee composer or a NC composer? And since I was born in the TN mountains, am I an APPALACHIAN composer (I’ve seen my share of “Appalachian springs” 🙂 ???? Maybe I would be “Hillbilly composer” and I could write a “Hillbilly Elegy.”

It’s Spring Break, so I’ve got too much time on my hands.

So is it about place of birth, cultural imprinting or genetic ancestry?

Or simply a diverse mixture – like in the case of Mahler or Still?

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Grant_Still

Good question. But does place of birth, cultural imprinting or genetic ancestry have anything to do with what goes down on a piece of manuscript paper?

Aaron Copland, in my opinion, did a great job of capturing the essence of Shaker life in Appalachian Spring. How did a New York Jew whose father was from Lithuania manage that?

My answer: talent, musical skill, imagination, listening carefully to things. But the three things in the first paragraph seem to have no effect.

As for Still, or Florence Price or Harry Burleigh, et al, while they wrote much music from their ancestral background they also wrote music that, if heard without knowing the composer, one might think was just a “generic” American (aka “white, European”) composer. They learned their music lessons well.

I really do enjoy this website.

Yes, just like Elgar who often sounds more Bavarian or Venetian than English.

Or like the brilliant John Williams who captures the spirit of Abraham “Lincoln”, reflects the Jewish idiom in “Schindler’s List”, and rides through England’s green and pleasant land on a broomstick.

To use the word ‘Sudeten’ in reference to Mahler, Rilke or, for that matter, Adalbert Stifter, is an anachronism. The Culture Minister may have been using it as a kind of shorthand, but it doesn’t seem right. Perhaps she said it with an eye to the Expellee organisations in Germany. The German language-island around and including Iglau had its own dialect and Mahler may have spoken German, at least when he was young, with an Iglauer twang. Perhaps de la Grange mentions it.

Alma mentions in her memoirs that Mahler had difficulty pronouncing certain letters.

What she says is foolish (to be polite). She is of course wrong about Mahler, German speaking Jews never considered themselves “Sudetendeutsch”. Neither did the German speaking inhabitants of Prague (Rilke).

What the unfortunate Ms. Grutters obviously does is what quite a few Germans mistakenly do: They erroneously think that everything which seems to be German and/or speaks German must somehow be German. Quite interesting for a country where especially politicians, academics and artists pride themselves with avidly studying history and learning from the past.

NL is totally right: a particularly ugly distortion.

Well said!

I suddenly realize that my own Deutsch may be a secret and unintentional cultural appropriation.

What are Germans?

Who am I?

https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Deutsch_(Etymologie)

There are so many different Germans and German manifestations that it seems better to compare ‘Germany’ with India.

Gustav Mahler war KEIN Sudetendeutscher! Noch heute wird dieser “politische Kampfbegriff” – der zu Beginn des 20. Jahrhunderts erfunden wurde – fälschlicherweise gerne für ALLE (bis 1938) deutsch sprechenden Bewohner der Tschechoslowakei verwendet. Besonders wenn sie prominent sind wie Gustav Mahler, Franz Kafka, Sigmund Freud und auch mein Großvater Hans Winterberg. Sein kompositorisches Werk liegt “weggesperrt” im Sudetendeutschen Musikinstitut in Regensburg.

Im volkstümlichen Sprachgebrauch wird die Bezeichnung “Sudetendeutsch” für alle am Ende des Zweiten Weltkrieges aus Tschechien AUSGEWIESENEN deutschsprachigen Einwohner benutzt. In präzisen Sprachgebrauch werden als „Sudetendeutsche“ nur diejenigen ehemaligen tschechoslowakischen Staatsbürger bezeichnet, die sich zur sudetendeutschen völkischen Bewegung bekannt haben und heute bekennen, sei es durch ihre aktive Partizipation am sozialen, politischen und kulturellen Leben dieser Bewegung, oder durch ihre aktive Unterstützung ihrer politischen Repräsentation (1933-1935 Sudetendeutsche Heimatfront, 1935-1938 Sudetendeutsche Partei, 1938-1945 NSDAP und nach dem Zweiten Weltkrieg die Sudetendeutsche Landsmannschaft).

Keiner der oben genannten wurde jemals “ausgewiesen”. Weder im volkstümlichen, noch im präzisen Sprachgebrauch gibt es Hinweise darauf, deutsch sprechende Juden als “Sudetendeutsche” zu bezeichnen. Es sei denn man bezweckt dass alles, was deutsch zu sein scheint und / oder deutsch spricht, irgendwie deutsch sein muss, auch um diese Prominenten zu Deutschen machen zu können.

Dass die Juden in der Tschechoslowakei überwiegend Deutsch sprachen, ist den Toleranzedikten Kaiser Josephs II. (1782) geschuldet, die im Rahmen seiner Reformen, die den in den österreichischen Erblanden zuvor diskriminierten Minderheiten eine freiere Ausübung ihrer Religion ermöglichten. Deutsch wurde zur Staatssprache…

Also war Mahler per historischer Definition ein “Sudetendeutscher”, was als Sammelbegriff sich zunächst auf die deutschsprachige Bevölkerung in den Ländern der böhmischen Krone bezog und “Deutschmährer” (Mahler) explizit einschloss.

Der bittere Beigeschmack kommt mit dem Verbot der Bezeichung “Deutschmährer” (und “Deutschböhmer”) in der Tschechoslowakei und dann mit der Vetreibung der “sudetendeutschen” Minderheit nach 1945.

Nach heutiger Definition wäre Mahler ein Tschechischer Komponist.

Oder ein Komponist der Europäischen Union?

Aber das alles ist doch eigentlich Wurscht, da Mahlers Werk zeitlos und nicht ortsgebunden ist.

So what’s the fuss?

Mahler was a EU composer, like Ravel but not like Stravinsky.

Not like Grieg and Raff.

Erst lesen, dann denken und dann schreiben.

Erst schlafen, dann denken, dann lesen und wieder ins Bett.

Erst trinken wir – prost!

It is 61 years old news now, but at least it is funny and tells a bit. 1960 after Nazi-world-war Germany had still – well, not ignored, but surely not celebrated – Mahler’s 100th birthday.

The wonderful conductor I pick my nickname from, Otto Klemperer, wrote to “Der Spiegel” in disgust, and, telling them how Germany had neglected Mendelssohn-Bartholdy’s 150th birthday and Mahler’s 100th, ended his letter with “Heil Hitler”. (Funny as Klemp was, he added he hoped the paper would spot the sarcasm^^. I guess they did.)

Unlike many of you I don’t belong to the people who are so happy as to be able to go to dozens of wonderful concerts. Think we could go back in time! Still I know that beginning around 1966, 67, slowly Mahler became very famous in Germany, too. The years where Bruno Walter, Klemperer, Mengelberg (later a Nazi? I have to check, but surely you know), Mitropoulos had fought for Mahler, 1910-60, somehow went unnoticed. And antisemitism, plus additionally maybe ignorance (there are so many possibilities, people are difficult) did a lot.

Today, and I guess since at least 1980, views like the musical statement by Celibidache that Mahler (from memory) “was a mistake” – are a real rarity here. Still of course people are not whistling the beginning of the 6th in the street (somehow would be funny, let us do it, where ever you are).

Then – officials… someone writes a speech and they look onto a teleprompter or read their phones.

To end this somewhat lengthy comment, I just received a new box with Mahler 2 and Kindertotenlieder with Kathleen Ferrier, Jo Vincent and Klemperer, Holland festival July 12, 1951. I simply love this concert, it started with Mozart, KV 477. (There is also Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen, Amsterdam 1947).

Music is – after all and after really a lot is discussed, like the ignorance of some philistines (they just call themselves “cool” now, to hide their disinterest) also a matter of taste. I hope you all have memories of outstanding concerts, and surely Mahler is widely played since 5 decades and that won’t ever change, I hope. To me it is just as beautiful to listen to those old and newer recordings. In fact it is heaven. And to sit down with the score and to listen to what 2 or 3 who knew Mahler well and saw him conducting make of a Mahler symphony – it is amazing.

The question is – why do people who seem not to be much interested in music but want to tell how great they “inscene themselves” and how great they themselves were, talk about Mahler at all. (Well, Klemperer would maybe think “better than to neglect the master”).

Just checked: at least the lady who talked is responsible for giving 5,4 millions Euro to free orchestras like the Freiburg Barock orchestra and the Mahler chamber orchestra. Each ensemble, suffering from the lockdowns, gets 200 000 Euro. So maybe someone tried to get the word Mahler in her text. The orchestras could put more Mahler on their programmes – I am sure this is what Klemp would have done, or Bernstein.

This is a “we are the good ones” society, I am afraid.

Long live Mahler!

Do you happen to know where the article is? I’ve looked in the Spiegel archives and wrote to them about it and, alas, I haven’t heard anything back.

For me it amounts to an abuse to refer to Gustav Mahler as a “Sudeten German” – a political battle term for a certain group of ethnic Germans – and that has nothing to do with the fact that Mahler was German as mother tongue and culturally German. This also applies to Franz Kafka and Hans Winterberg.