An American pianist unlike any other

mainUpwards and Onwards

A Personal Remembrance of Daniell Revenaugh: May 30, 1934 – March 12, 2021

By Lawrence Perelman

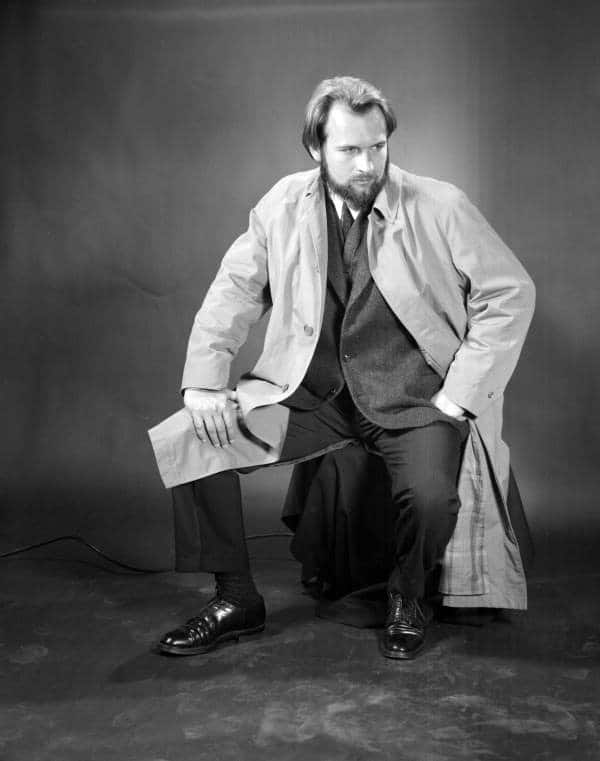

If you happened to drive or walk down the small two block Etna Street not far from the Berkeley campus in California over the past few decades you could often hear a piano being played. Not just any piano or pianist. Cutting a rugged figure more akin to a cigar chomping truck driver in his later years than the classical music enfant terrible of his youth, Daniell Revenaugh was a concert pianist, conductor, entrepreneur, inventor, impresario and arguably the greatest promoter of Ferruccio Busoni during the second half of the 20th century.

Although a Steinway artist, Revenaugh often preferred his Knabe concert grand over which he towered sitting on a tree stump he retrofitted into a piano stool. This was one of nearly half a dozen pianos he owned including the piano on which Liszt gave the first known piano recital in London in 1840. The figure he cut belied the nuanced and beautiful musical line he could produce on the Knabe. His Angel Records recording of Waves of the Danube by Ion Ivanovici has been streamed over 365,000 times on Spotify and is a window to a style of piano playing long forgotten and forged by Busoni’s greatest pupil Egon Petri.

Daniell Revenaugh passed away on Friday, March 12, 2021 at the age of 86.

He was my friend and mentor. His family asked me to write a personal remembrance and asked that I share it publicly.

I often think that what has left us as a society with the advent of social media is the mentor protégé relationship, more so with the pandemic driving a wedge through the ability to meet in person at all for over a year. The virtual connection will never outweigh that of the in-person. This is the story of personal connection.

Our First Meeting: Cuban Cigars and Steinway Hall

In 1995, I was fortunate to receive a box of twenty-year old Cuban cigars from a family friend who brought them over when fleeing the Soviet Union in the early 1970s. Then 19 and studying to be a pianist in New York, I had never smoked a cigar but thought there might be value to them. Looking for someone to perhaps purchase them I mentioned these cigars to the receptionist at the now sadly closed Steinway Hall showroom on 57th Street where I often practiced. She in turn said that Daniell Revenaugh would be in New York soon and had an interest in cigars and could provide some answers. The name did not mean much to me except for a vague recollection that he had conducted a recording of Busoni’s Piano Concerto with John Ogdon.

A few weeks later Revenaugh phoned me and in what would become a familiar to the point style of communication he began, “I hear you have some Cuban cigars.” We naturally arranged to meet at Steinway Hall. He took one look at the box of Romeo y Julietas and proclaimed, “these are crap.” He told me that the Cubans would ship the Soviets their worst machine-made cigars in exchange for goods. He wasn’t interested in the cigars, but a quarter century friendship had commenced.

This was my introduction to someone who I soon realized was underappreciated by the classical music industry both due to its conservative tendencies during his youth as well as his often times brusque demeanor. Over the years I understood that the latter was more a function of his quickness and ability to see the solution to a problem but reluctance to deal with the operational realities that surrounded getting to that solution. In many ways this was an admirable trait, one that of a dreamer, visionary, impresario and entrepreneur. On the other it might have inhibited some of his visions from coming to fruition.

As I got to know this iconoclastic personality it became clear that he was in fact an inspirational figure in classical music, even his generation’s classical music futurist. It did not matter much to me that the industry did not recognize this during the course of our friendship. However, as he has now passed on, it is important for me to put an exclamation point on just how relevant a figure I think he was even though there are many more reading this who will not know his name than know it.

Revenaugh’s Biography and Milestones

Daniell Revenaugh was born in Louisville, Kentucky on May 30, 1934. His father was a major in the US military and in charge of some military hospitals while stationed in Europe during World War II. His mother was a member of Diaghilev’s legendary Ballets Russes having danced with Fokine himself. Showing musical promise at an early age he made his debut at the age of 14 playing Beethoven’s Piano Concerto No. 1 with the Louisville Orchestra.

In 1951, Revenaugh began over a decade of study with the legendary pianist Egon Petri, Busoni’s most prominent pupil, continuing a pianistic line that could be traced back to Ludwig van Beethoven. He recognized that Busoni was not only underappreciated but a truly transformative musical figure. By his early 30s he became the foremost promoter of Busoni’s musical legacy founding The Busoni Society in 1965 with Busoni pupils Rudolph Ganz and Gunnar Johansen.

On January 26, 1966, Revenaugh produced and conducted a Busoni 100th Anniversary concert at Carnegie Hall featuring the New York premiere of the composer’s epic 70-plus minute Piano Concerto No. 1 performed by Johansen, a seventy-member chorus and the American Symphony Orchestra. Getting to that day was no small feat and he outsmarted none other than George Szell and the Cleveland Orchestra who thought they were going to have the premiere two weeks later. In a twist of fate, the publisher of the concerto let the rights lapse and this cleared the road for Revenaugh to proceed with the premiere with parts acquired from various far flung sources.

In June 1967, Revenaugh oversaw and conducted the first commercial recording of the work with pianist John Ogdon, the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra and the John Alldis Choir for EMI at Abbey Road Studios. A bevvy of recordings of this concerto have been made in recent years but this one was the seminal event in the Busoni renaissance he spearheaded.

One of the great anecdotes Revenaugh shared with me was a risky journey in his VW van from Vienna to Petri’s old residence in Zakopane, Poland. He and a friend outfitted the van with trunks loaded with goodies for the border guards. He and his friend then filled those trunks with vast parts of Petri’s library along with hundreds of letters between Petri and Busoni, and other classical music relics. This would form the core of a collection that Revenaugh cataloged into what is still the single largest collection of Busoni archival materials in private hands.

In addition to Petri, Revenaugh was also a pupil of Ernst von Dohnányi, Darius Milhaud and spent six months in Vienna at Herbert von Karajan’s invitation attending all of his performances at the Wiener Staatsoper. During this time, he befriended pianists Paul Badura-Skoda and Jörg Demus. He later became a protégé of Rudolf Kempe’s until that great conductor’s untimely death.

Revenaugh was the founding general director of the Institute for Advanced Music Study in Crans-Montana, Switzerland where in 1973 he invited some of the greatest artists of that era to serve as faculty to students on full scholarship. They included Zino Francescatti, Gregor Piatigorsky, Ib Lanzky-Otto and Kempe.

In the 1990s, Revenaugh invented and patented the Lower Lid for the concert grand piano with the goal of capturing and redirecting sound lost under the piano into the concert hall. The invention which made the concert grand piano look like a butterfly, sparked media attention along with the interest of many pianists including Martha Argerich, Radu Lupu, Peter Serkin, Alexander Toradze, and André Watts. They all performed with the Lower Lid in many of the world’s leading concert halls. In 1997, Carnegie Hall would not allow Argerich to use the Lower Lid and the story made Page One of The New York Times.

In between all of this Revenaugh traveled widely as a pianist and conductor, created a first of its kind Electric Symphony Orchestra in the 1970s with amplified instruments garnering national attention; produced Classical Cabarets in the 1990s; performed the complete piano sonatas by Schubert in 1997 marking the bicentennial of the composer’s birth; and was a hibernator of ideas that he thought could perpetuate interest in classical music by the broadest possible audience.

Revenaugh’s friendships were vast and stretched from all of those named above to many more. For example, fellow Berkeley resident Kent Nagano sought out Revenaugh for guidance when he was studying Busoni’s operas.

When you caught him at the right moment Revenaugh was a one-man cigar filled salon of anecdotes. One of my favorites was about how George Martin commandeered some of the musicians from the RPO during the Busoni Piano Concerto recording sessions in 1967 for the Our World Global Satellite Broadcast of “All You Need Is Love.” Revenaugh was invited to attend this historic live broadcast and showed me photos from that remarkable day.

Some Favorite Personal Memories: The Lower Lid and Martha Argerich

In 1997, two years after we had met Revenaugh asked me to transport one of his Lower Lids from Minnesota, where I had grown up and was finishing college, to Montreal. Radu Lupu had just used the Lower Lid with the Minnesota Orchestra and now Revenaugh’s friend Martha Argerich had agreed to use it in Montreal in performances of Prokofiev’s and Bartok’s 3rd Piano Concerti with the Montreal Symphony and Charles Dutoit. (Revenaugh met Argerich at the Deutscher Schallplattenpreis ceremony in Berlin in 1968 when the Busoni Concerto recording received the prize.) I was a starry-eyed 21-year-old and agreed to bring the Lower Lid to Montreal. The Lower Lid would attach to the piano with several hinges that clamped onto the back of the piano. These clamps ended up in my luggage, which I would regret checking, while the Lid itself traveled in a bicycle box in cargo. The box arrived, my luggage didn’t.

Needless to say, Revenaugh was furious with me but after venting about it he came up with a solution. He always did. We were backstage before the rehearsal started and he said, “you’re going to hold the Lid up while Martha plays.” I was shell shocked at the idea but there was no looking back. I soon found myself under the concert grand piano holding the Lower Lid up as Martha Argerich sat down at the piano and looked at me amusingly. As for Dutoit, at whose feet I sat with my elbow on the podium, he gave me a smirk. The rehearsal was triumphant, my shoulders were sore, and the clamps arrived in time for the concerts which were a success. That was the week I met Martha Argerich and for a young pianist it was the honor of a lifetime to hear her perform live in-person for the first time.

Revenaugh understood the power of the moment and the indelible impression it would leave on everyone.

Argerich would become a friend and I produced her comeback recital at Carnegie Hall on March 25, 2000. Bringing that concert to fruition had its own series of challenges which somewhat mirrored what Revenaugh had gone through in 1967. His advice and guidance were invaluable and gave me a solid foundation on which I have built ever since.

Revenaugh’s Legacy

In many ways Revenaugh was a Panglossian figure who might not have achieved the full potential of his musical and artistic gifts. However, what he left us, especially those who knew him well, was an understanding that bringing an idea to fruition could take a lifetime especially if it did not fit the narrative of the establishment. Why did a piano need a second lid? Why did an orchestra need to be amplified? Why match a cabaret with classical music? Why spend a lifetime preserving and promoting the legacy of Busoni?

Revenaugh could have dedicated himself entirely to the piano or conducting but instead lived by the words of Ralph Waldo Emerson, “Do not go where the path may lead, go instead where there is no path and leave a trail.”

Thank you for leaving that trail, my friend. I will continue, as you always said – “upwards and onwards” – and work to inspire others to leave a trail with me in your memory. RIP.

Lawrence Perelman is the Founder & CEO of Semantix Creative Group, a strategic advisory firm whose clients include the Salzburg Festival and Gianandrea Noseda.

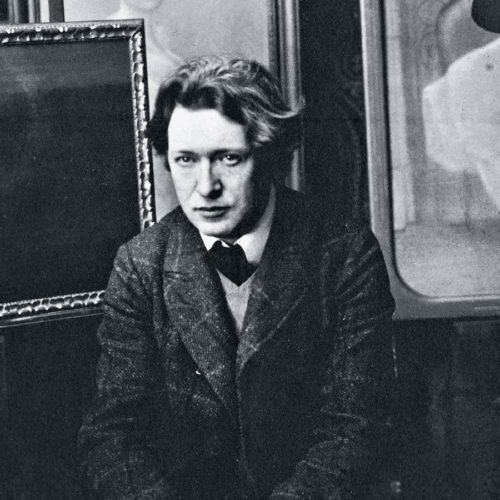

Ferruccio Busoni

Comments