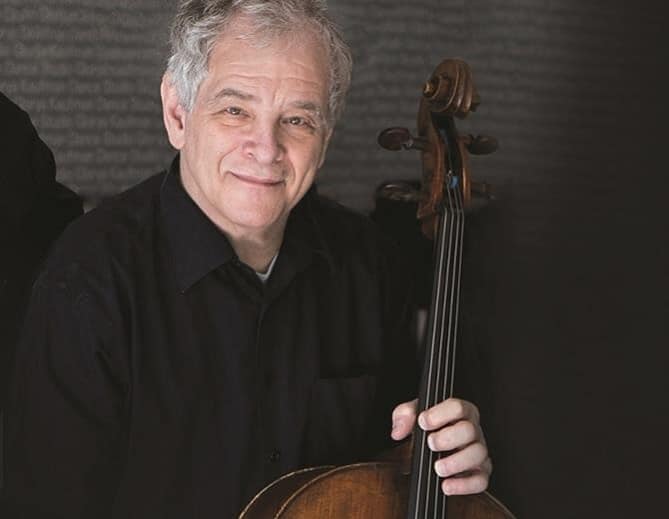

Alfred Brendel, 90: ‘I long for the physicality of a concert’

mainThe pianist, who turns 90 tomorrow, has given a few reflections to the German press agency.

On Covid: We all long for the physicality of the concert, to be there, to be inside, to breathe the same air, to share the risk and success.

On Brexit: I put great hopes in the UK, which was not so great within the European Community. However, the political development of recent years has rid me of illusions.

On his career: I gave concerts from the age of 17 to 77.

Comments