Fabio Luisi arrived as music director, facing a depleted and distanced ensemble.

Another Covid occasion.

Read here.

Fabio Luisi arrived as music director, facing a depleted and distanced ensemble.

Another Covid occasion.

Read here.

Welcome to the 115th work in the Slipped Disc/Idagio Beethoven Edition

Franz Liszt/Ludwig van Beethoven: Fantasia for Piano and Orchestra on motifs from Beethoven’s ‘The Ruins of Athens’

We have seen what Liszt did for Beethoven. We know, too, of Liszt’s role as a catalyst between the age of Beethoven and that of Richard Wagner. Liszt, who became Wagner’s most loyal supporter and eventually his father-in-law, often played Beethoven sonatas for Wagner, on one occasion, reducing him to tears in the slow movement of the Hammerklavier sonata.

Liszt carried much of Beethoven’s in his head, borrowing a theme here or there in his own scores. The most famous of his borrowings is the incidental music that Beethoven wrote for an 1811 play, The Ruins of Athens. Liszt decided that what Beethoven’s orchestral score needed was a prominent part. The result is a cataclysmic horror show, the sort of thing a stand-up comic like Dudley Moore would write as a parody of Beethoven or Liszt, or both of them together.

Liszt published his tribute in three versions – for solo piano, two pianos and piano and orchestra – all of them dedicated to the Russian pianist and composer Nikolai Rubinstein, who was his arch-rival at the time. In the version with orchestra, Liszt keeps the piano under wraps for a long stretch, before blowing in the soloist with a storm, soon followed by Beethoven’s Dervish Chorus and his overworked Turkish March. It’s fun and frisky and possibly self-mocking.

There are several recorded versions of varying degrees of seriousness, the earliest of which dates from September 1938 with the pianist Egon Petri and the London Philharmonic Orchestra, conducted by Leslie Heward, who was music director of the City of Birmingham Orchestra. It’s a buttoned-up strait-laced performance and all the better for that. Petri was an emigre Dutchman with Liszt-like hands who was much in demand for the most difficult and prestidigitatious works. His playing of this piece is practically unsurpassed.

A Russian recording by the USSR State Radio and TV Symphony Orchestra conducted by Alexander Gauk is interesting for the opportunity it afford to hear the pianist Grigory Ginzburg (1904-61), a Liszt specialist who was hardly ever allowed let out to perform abroad. It may be my fantasy, but I find an authenticity in his approach which stretches back to Rubinstein and Liszt himself. The sound is Soviet bog-standard, barely listenable in parts.

Of the remaining recordings, Kurt Masur has outstanding orchestral sound with the Gewandhausorchester Leipzig in 1991 and Michel Béroff as soloist, but takes the whole thing too seriously.

One other Liszt tribute to Beethoven we need to consider is his

Inauguration cantata for the Beethoven Monument in Bonn

The words warn you to expect a sententious, sancimonous exhortation at an occasion attended by the crowned heads of Europe, and the music lives down in every section to our lowest expectation:

Holy! Holy! Holy

is the genius’s sway on earth.

He lent us a foretaste of heaven,

immortality’s surest pledge.

This celebration has united us!

Set foot within the circle;

let us devote these varied hours

to his memory...

There are moments – the start of the third movement, for instance – when Liszt displays his mastery of orchestral invention but barely has he drawn us into a theme that he sets a soloist loose on a tangent that has nothing to do with the musical context.The finale, marked ‘andante religioso’, smells of incense and baked beans.

There appears only ever to have been one recording: by Bruno Weil in 2020 with the Cappella Coloniensis, Kölner Kantorei and soloists Diana Damrau, Jörg Dürmüller and Georg Zeppenfeld. Listen to it here. Don’t say you haven’t been warned.

On a more reasonable note, Liszt’s transcription for piano solo of Beethoven’s love song ‘Adelaide’ is pure pleasure. Egon Petri gives a reminder that muscular pianists can also be microsurgeons, while Garrick Ohlsson in far superior sound suggests at hidden affinities between Beethoven, Liszt and Schubert. It’s ten minutes well wasted.

Robert Schumann: Studies in the Form of Free Variations on a Theme of Beethoven

In 1830, the profoundly insecure 20 year-old Schumann was writing piano studies on Beethoven themes that would never be played or published in his lifetime. This singular set is built around the second movement of the 7th symphony and is riveting for the way we hear Schumann learning point by point from the master which angles to use in developing a theme. At around eleven minutes you will hear an echo of the opening of the 9th symphony and wonder what it’s doing there.

The Etudes are rarely progarammed in recital halls. The most compelling available performance on record is by the London-based Hungarian pianist Peter Frankl, a scintillating retracing of Schumann’s rising excitement as he discovers the means that Beethoven puts at the disposal of future composers. I have never heard this set performed live and it’s now near the top of my wish-list. Frankl, who is 85 next month, still gives an occasional recital.

Other interpretations can be heard from the Frenchmen Simon Ghraichy (2019) and Eric Le Sage (2010), both distinctly different.

Naive Classics, which went a bit dormant, has bounced back with three signings.

They are pianist David Greilsammer, cellist Christian-Pierre La Marca and chamber group Trio Sōra.

A decade ago Slipped Disc produced a list of publisher’s hits which put Karl Jenkins in the #1 spot and Joan Tower in second.

Wonder what’s changed?

Publishers are invited to send us a list of their most performed scores by composers who are still standing.

2010 list here.

The Guardian has published rankings. You’ll never guess who’s come top.

Second is Southampton (!), third Oxford.

Royal Academy of Music ranks 13th.

Full list here.

The BSO has just put out this statement:

In response to COVID-19-related revenue loss of $35 million, a compensation reduction averaging 37% in the first year of the contract; increases in compensation over the course of the agreement will occur as the BSO redevelops sustainable revenue, as clearly defined in the terms of the new contract….

The Boston Symphony Orchestra’s new labor agreement reflects our collective understanding of the major challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic and the devastating financial losses due to the cancellation of the BSO’s performance and event schedule, March-November. By addressing these challenges on the compensation level, as well as in several other areas, the BSO’s new labor agreement acknowledges the part the musicians are playing in the overall cost-saving measures to ensure the Boston Symphony Orchestra emerges from the pandemic as a vibrant and essential institution for its loyal music community. It was especially gratifying to come to an agreement on the importance of redefining official services beyond rehearsals and concerts during this time of hiatus from live performances and beyond. In a departure from the standard labor agreement subjects, management and musicians worked enthusiastically together on the creation of the BSO Resident Fellowship Program for young musicians of color—a program that we hope will inspire much needed optimism as we continue to look toward better times and toward expanding the BSO’s vision of its future offerings.

Just released: my debut performance at the Wigmore Hall, discussing themes from my book, Genius and Anxiety.

The brilliant pianist illustrating my talk is Daniel Lebhardt.

The five composers discussed are Mendelssohn, Alkan, Mahler, Schoenberg and George Gershwin.

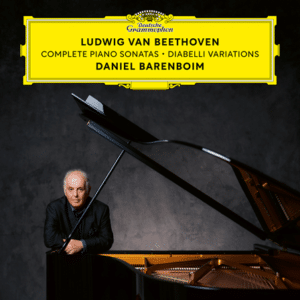

He recorded the 32 Beethoven sonatas.

Again?

It’s the third or fourth time.

He says: I was delighted that, thanks to Deutsche Grammophon and its partners, hundreds of thousands of listeners around the world were able to share in the live-streamed concerts we gave in April from the Pierre Boulez Saal. To have the chance to record Beethoven’s sonatas so soon after for the Yellow Label felt like the ideal response to the pandemic. At no point during the last fifty years has there been a period when I’ve had time to spend three whole months just playing the piano.’

Out next month.

From the Lebrecht Album of the Week:

I often wonder when listening to X’s music why he is not one of the most performed living composers. His music is at once mentally challenging and aurally agreeable, beautifully constructed and unexpectedly affecting. He ought to be in every concert season.

Born in Kiev in 1937 and a major catalyst in the 1960s Moscow avant-garde, he was named ‘one of the greatest composers of our time’ by such distinguished colleagues as Alfred Schnittke and Arvo Pärt. Yet as far as western conductors are concerned he might as well be an Mongolian herdsman for all the attention they pay to his output. He’s 83 and still writing. Listen up now….

Read on here.

In The Critic here.

And here.

In Spanish here.

In Czech here.

In French here.

Trouble ahead in Minnesota.

Minnesota Public Radio’s only Black classical music host Garrett McQueen has announced on social media that he’s been fired.

Garrett was presenter of Music Through the Night. He has played in a number of orchestras including South Arkansas Symphony, Jackson Symphony and American Youth Symphony.

McQueen said he was taken off the air after his shift on Aug. 25. He was then given two warnings — one of which was about his need to improve communication and the other warning was for switching out scheduled music to play pieces he felt were more appropriate to the moment and more diverse….

More here.

We wonder what he played instead of the usual sleepy stuff.

For the past six months of lockdown, London’s largest classical agency has vanished into a bunker, issuing barely a peep.

We understand that a quarter of the staff have been shed – 24% to be precise – not all of them consensually. Others are working a 4-day week while the lavish offices stand empty.

However, today there are signs of life.

We hear that AH have signed a co-production deal with the Met for its filmed recitals, starting tomorrow with Joyce DiDonato. The costs are high but the credit’s worth something.

There are also new signings on the cards, the first of whom is the fast-rising French soprano Elsa Dreisig, who stole the show as Fiordiligi this summer in Salzburg’s Cosi fan tutte.