Why composers get silenced when they die

mainFrom the Lebrecht Album of the Week:

It is a grim fact of musical life that, when a composer dies, his music goes into limbo for at least ten years. In that time, music directors and programmers shove the complete oeuvre into a drawer and wait, they say, for the reputation to settle. For a few lucky composers, a decade passes and there is a revival. For the others, just silence.

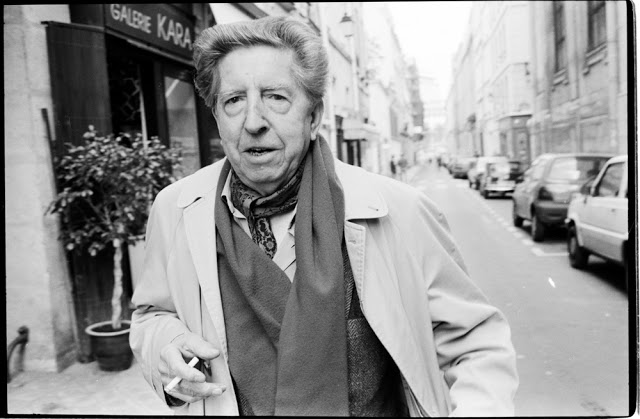

The French composer Henri Dutilleux died in May 2013 at the age of 97. All his life Dutilleux struggled to make himself heard …

Read on here.

And here.

And here (in Czech)

And in Spanish

Comments