The Emperor’s old clothes

mainWelcome to the 85th work in the Slipped Disc/Idagio Beethoven Edition

Piano concerto no 5, ‘the Emperor’, opus 73 (1809)

The fifth of Beethoven’s piano concertos was given its title by a British publisher, not in homage to any imperial personage, rather as a statement of its obvious supremacy over any concerto ever written before. It was the last Beethoven would write, no longer trusting his hearing to allow him to balance the solo part against a full orchestra.

The Emperor Concerto quickly became his most popular orchestral work. It appealed on first hearing not just to concerthall regulars but to many first-timers who had experienced orchestral music, or western music at all. In Rukun Advani’s 1994 Indian novel Beethoven Among the Cows, the two protagonists find the Emperor Concerto helps them ‘transform soulful torment into aesthetic torrent…. There was an immense, impassioned, ordered turbulence about the music which set in perspective everything else in life and made it seem the highest cathartic interruption within the general desirability of silence.’

This is a strikingly fine description of the processes of Beethoven’s mind during Napoleon’s siege of Vienna, his determination to use music both to represent the terrifying danger and chaos and, gradually, to achieve understanding and calm. This effect found its way into many movies. The slow movement is heard at the close of the 2010 movie The King’s Speech, signifying George VI’s deep satisfaction at his triumph over a debilitating stutter. Other films that utilise this movement include Picnic at Hanging Rock (1975), Dead Poets Society (1989), Elysium (2013) and Crime of Padre Amaro (2002).

The original concerto received its first performance in January 1811 with Beethoven’s pupil, Archduke Rudolf, as the soloist at a private gathering in Prince Joseph Lobkowitz’s palace. The public premiere was given ten months later. Its consolatory aspects notwithstanding, the bombastic title has led the work to be scheduled at political and rhetorical occasions and t acquire unfortunate associations.

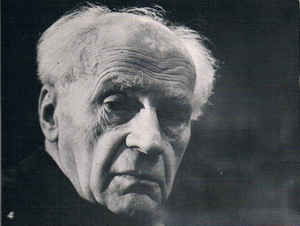

Its most prolific performer, the German pianist Wilhelm Backhaus, did his utmost to identify the concerto with the Nazi cause. The Emperor was Backhaus’s calling card. He played it, aged 27, at his US debut in New York in January 1912, and he was the first to play it in a record studio 15 years later, with Sir Landon Ronald and the Royal Albert Hall Orchestra. This was the first of a dozen recordings he made over the course of the next four decades. Backhaus, who styled his photographic poses to resemble, was the first-choice soloist in this concerto in the world’s most pretigious concoert halls and you can hear why in this enduringly effective 1927 recording.

His opening trademark is nonchalance, a series of glittering keyboard runs that assert his casual command of the work and its absence of any difficulty for a titan of his stature. The element of struggle, so integral to Beethoven, is missing from the Backhaus makeup. What he supplies instead is a certificate that this is one of the highest achievements of human civilisation, delivered by a dedicated and accomplished exponent. Some aspects of this first recording are almost unsurpassable.

Six years later, in April or May 1933, Backhaus met the new German Chancellor Adolf Hitler on a flight to Munich and became his musical acolyte. Hitler appointed him head of a Kameradschaft der deutschen Künstler (Fellowship of German Artists) and Backhaus reciprocated with a public statement that ‘Nobody loves German art and especially German music as glowingly as Adolf Hitler’. In April 1936, Hitler gave him the title ‘professor’ and in September that year he invited Backhaus as his personal guest to the Nuremberg Rally.

Backhaus, who had taken Swiss citizenship in 1930, would later attempt to conceal these facts and maintain a pretence of neutrality in a prolific post-War career. His 1959 recording of the Emperor with the Vienna Philharmonic, conducted by the non-Nazi Hans Schmidt-Isserstedt, displays the same clarity of expression, the same unflappability and perfect profile. The politics of Backhaus are immaterial to his surreal ability to detach himself from the moment of playing and deliver serenity wherever he performed.

Four other Emperor specialists were tainted by Nazi affiliations. Elly Ney, who played through a Berlin air raid, adored Hitler, hated Jews and took part in Nazi ‘cultural education’ camps. The other three are more important. Walter Gieseking, who was French born, was quoted by Arthur Rubinstein with the statement ‘I am a committed Nazi. Hitler is saving our country.’ But Gieseking was also a modernist who played Hindemith and Schoenberg and brought a refreshing lack of agenda to his playing. His Emperor concerto, played in Berlin in January 1945 is almost extra-terrestial in its serene disregard for the hell that must have been raging outside.

Wilhelm Kempff, who performed for Nazi leaders a few short miles from Auschwitz, was the pre-eminent German pianist on record in the 20th century. As with Backhaus, there is no perceptible difference whether he plays with a fanatical Nazi conductor like Peter Raabe (1935) or the progressive Ferdinand Leitner (1961), the latter recording being one of the most appealing of all accounts of the concerto.

The last of our compromised pianists was the Swiss Edwin Fischer who blotted his copybook by grabbing Artur Schnabel’s professorship in Berlin in 1933. He continued to play a role in Nazi Germany until 1942, at which point he went home to Switzerland and stayed very quiet until after the War. Fischer made no adulatory statements about Hitler and did not join the Nazi party. His 1951 recording of the Emperor, with the Philharmonia Orchestra and Wilhelm Furtwängler, is instructive in many ways, astonishingly fluid in its speeds and unexpectedly smiling in its mood. Fischer went onto be the cherished teacher of Alfred Brendel, Daniel Barenboim, Paul Badura-Skoda and Jörg Demus – a gateway to the future of Beethoven pianism – and i regarded as one of the high intellectuals of the keyboard. His collaboration is something we have to consider and contextualise.

Artists are as fallible as the rest of us in respect of political judgement. They make mistakes that they later obfuscate or deny. They maintain that whatever ideology they might have espoused it did not affect the music they performed – a valid argument, as we can hear from these recordings. It is, though, important that the listener should be in possession of the facts in order to form an independent. And when the rack of Emperor recordings is topped by five such compromised characters it may say something significant about the concerto itself and its easy, unthinking popularity.

Havign set these contenders to one side, we can now survey the rest of the field tomorrow with greater equanimity.

Comments