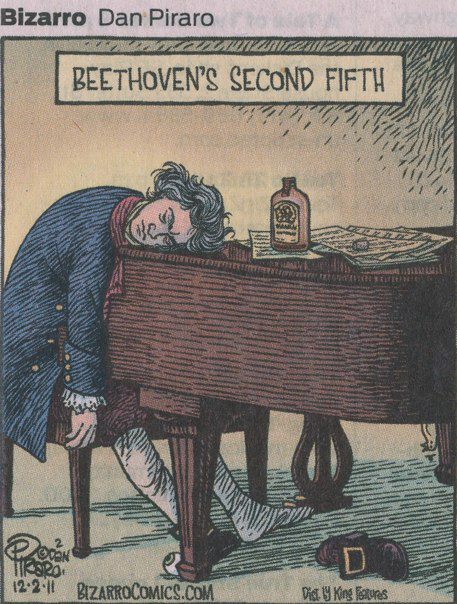

Was Beethoven drunk?

mainWelcome to the 69th work in the Slipped Disc/Idagio Beethoven Edition

Piano sonata no 21, Waldstein, opus 53 (1805)

If you want to think like Beethoven, eat like him.

Given his general lack of order and personal hygiene, it comes as a surprise to find that his diet was quite healthy. The woods around Vienna were rich in mushrooms and berries, the fields in root vegetables. There was asparagus in season and fish was fresh from the Danube. Beethoven was said to be partial to pollock and pike-perch. On the whole, he preferred fish to meat, though he usually had a stew on the go and he kept a salami in the larder. He was not a tidy eater.

For carbohydrates, he liked pasta, preferably macaroni. A legend flourished that he liked macaroni cheese.

If so, it would have been Italian parmesan.

On Thursdays, he ordered bread soup with ten eggs beside it on a plate.

The single most important item in his daily intake was coffee at breakfast, ‘which he usually prepared in a glass machine’. His devoted friend Anton Schindler continues: ‘Coffee seems to have been his most indispensable food, and he prepared it as scrupulously as a Turk. Sixty beans were calculated per cup and he would often count them out, especially when guests were present.’

He liked a glass of wine in the evening at Vienna’s White Swan bar in the Neue Markt. In one letter he writes: ‘Let us meet at seven this evening at the Schwan and drink more of their disgusting red wine.’ There is a theory that lead in cheap wine contributed to his kidney problems. He seemed to have no nostalgia for the astringent whites of his native Rhineland. His father had been an alcoholic, often in trouble with the police, but there is only one report of Beethoven being mistaken for a tramp as he staggered home from the pub, and that account may be apocryphal. Intemperate in so many others ways, he either handled his drink well, or he simply did not drink that much.

Does it matter to our understanding of his works to know what he ate and drank? I think it does. Although he lived in the most appalling squalor and dressed in torn clothes when he could have afforded better, there is an impressive order to his menu. Beethoven ate at fixed times and took regular walks. For all the chaos around him, he understood the creative imperative of good food and exercise.

The Waldstein Sonata – one of his three most popular after the Moonlight – would have been written in this general spirit of wellbeing and dedicated to his friend and patron, Count von Waldstein, who had long declared Beethoven to be the holy spirit in a trinity with Haydn and Mozart. The sonata has also been titled ‘L’aurore’, for ways that it evokes daybreak.

The three movements are, essentially, quick-slow-dance, but all three begin softly. The first known review concludse: ‘The first and last movements are among this master’s most brilliant and original pieces, but they are also full of strange whims and very difficult to perform.’ It lasts 25 minutes and there are almost 200 known recordings of this ever-popular work.

Wilhelm Kempff, a composer in his own right and a veteran of recording studios from the early 1920s, cannot be faulted in this sonata. The absence of any agenda, ideology or affinity in a piece that expresses no more than the joy of being alive allows Kempff to play with limitless freedom and fantasy. I find his 1964 recording to be his most satisfying, a master in command of his craft. All that is lacking is eros.

Vladimir Horowitz, recorded in his New York apartment in 1956, gives the middle movement an unmistakable languour of sex in the afternoon. Impossible to put one’s finger exactly on his G-spot but the eroticism of his interpretation can be almost overwhelming. There is even guilt to be heard between the notes. Who on earth was he seeing? Whoever it was, poor celibate Beethoven would have been envious. Friedrich Gulda (1958) has something similar in mind.

Arthur Schnabel was having a clandestine affair in the 1930s with an American admirer. Something of his seduction technique comes over in the middle movement, which begins as if he is requesting consent, knowing full well that his lover can’t refuse him.

The Scots pianist Frederic Lamond, who recorded in Mach 1930, was one of the last living students of Franz Liszt and therefore a useful clue to the generation immediately after Beethoven. I find his playing pedantic, schoolmasterly, colourless. This cannot have been Liszt’s way.

Benno Moiseiwitsch, a late-romantic specialist from Odessa much admired by the British aristocracy, recorded at Abbey Road in the middle of the Blitz. Emotion is suppressed behind a stiff upper lip, but the range of light and shade is reminiscent of another time and place. Moiseiewitsch studied in Vienna with Theodor Leschetizky. Perhaps he was thinking of a walk in the woods.

The English phenomenon known as Solomon, recording in 1952, treats the finale as an apotheosis, a hymn of redemption from external stresses of war, deprivation and slow reconstruction, one suspects. In all of these pianists, there is more imagination let loose than in the industrial-production recording machines of the 1970s and 1980s.

Emil Gilels (1972) is the great exception. His slow movement is an invitation to something other than intimacy. Gilels seems to be asking us to join him in a quest for nothing less than the meaning of life. He puts the question, then pauses. Puts another, then takes us by the hand. The way he involves a listener in his thought process is, to my ears, unique. Vesa Siren, the Finnish critic on our panel, says: ‘Every time other great pianists start to play Waldstein, for at least a brief moment I wish they were Gilels.’

It’s asking an awful lot of a 21st century pianist to join this exalted company of explorers, but Boris Giltburg (2015), Russian-Israeli winner of the Queen Elisabeth Competition in Brussels, has his own brand of daring and a wonderfully varied set of colours in which to expound it. He is still feeling his way into the literature at this time, but his foundations are secure and his promise high. This is a Beethoven artist who will grow and grow. I am surprised that his contemporary Daniil Trifonov, who often plays the Waldstein in recital, has not recorded it yet.

Clearly there is much more to be said.

Comments