Beethoven and his Jewish doctor

mainWelcome to the 65th work in the Slipped Disc/Idagio Beethoven Edition

An die ferne Geliebte, opus 98

Although I discussed this set in one of my first essays in this series, I am returning to it four months later in light of new research and some further isolationist thoughts occasioned by our peculiar present constraints.

In 1816, with Napoleon defeated and the leaders of unfree world gathering in Vienna to consolidate their unholy rule, Beethoven invented the song-cycle. He asked a friend, Alois Isidor Jeitteles, for some love poems he could set to music and found both the content and the form conducive to a linked narrative about a man, sitting on a hill, contemplating the girl he would never get. Since this was a valid reflection of his own unfulfilled love life, the cycle can be read in some way as autobiography, but it also needs to be seen in light of the relationship between Beethoven and the poet, a man 24 years younger than himself and from a different culture.

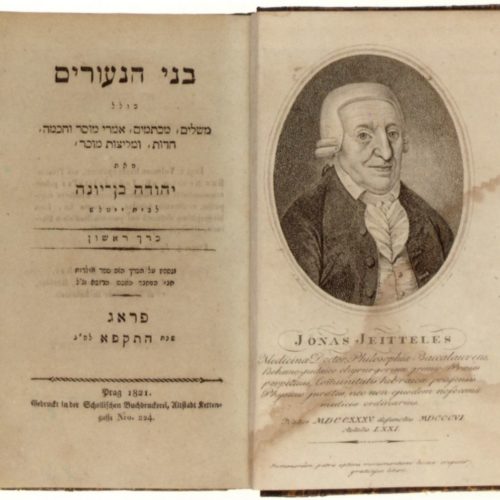

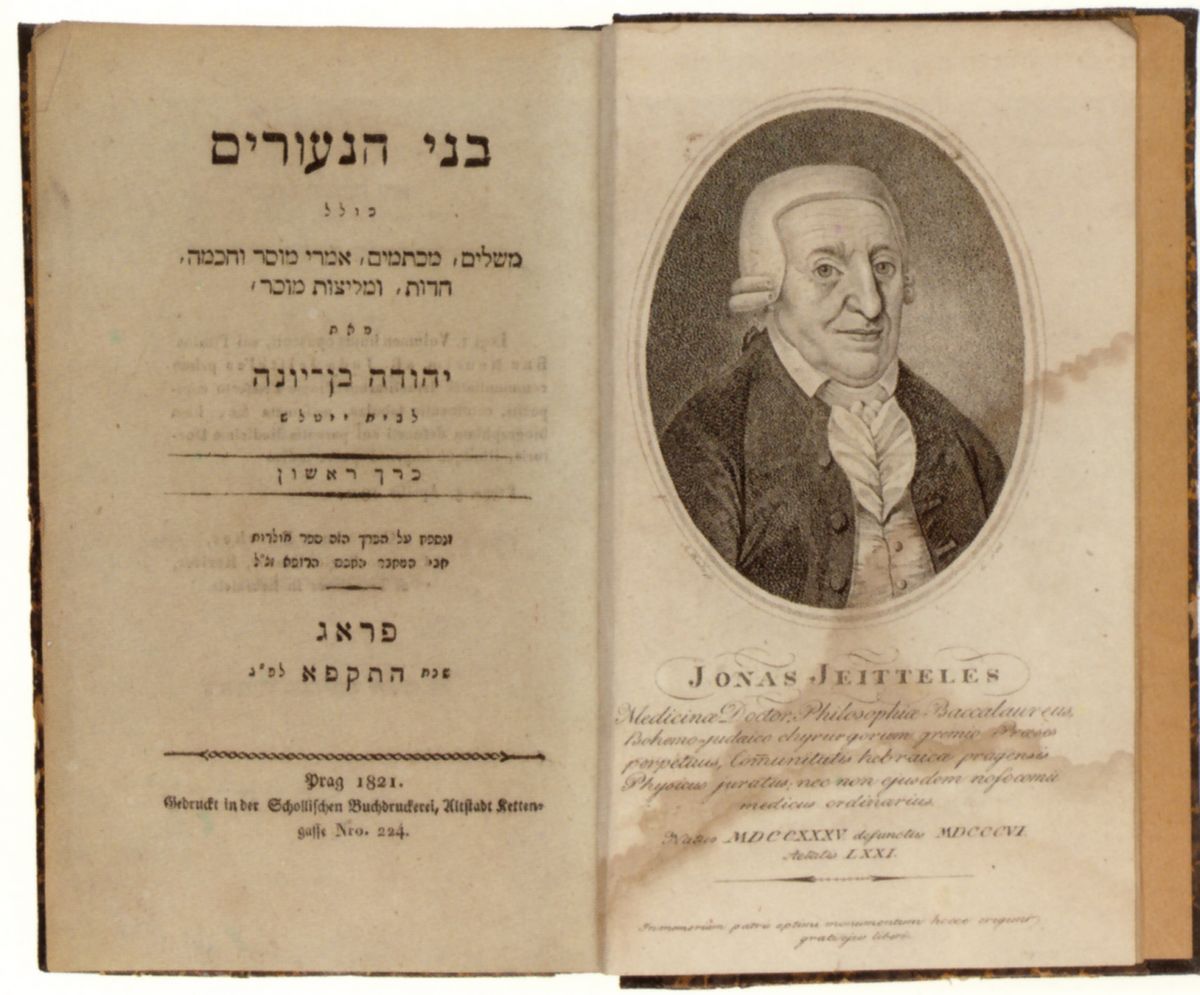

Alois Isidor Jeitteles came from the Czech town of Brünn (Brno), where as a student he founded and edited a Jewish weekly newspaper, Siona. His family were middleclass and erudite, with rabbinic scholars (pictured), doctors and writers among his Prague ancestors. Jeitteles translated plays from Spanish and Italian and wrote some successful ones of his own. After studying at universities in Brünn and Prague, he came to Vienna to complete his medical qualification, all the while maintaining membership of an artistic circle that included the influential playwright Franz Grillparzer as well as the no less manipulative composer Antonio Salieri. It was through this group that he obtained access to Beethoven and asked if he could submit his poems.

They arrived at a timely moment, just as Beethoven told one of his friends that he had ‘found only one, whom I shall doubtless never possess.’ What Beethovene expresses in his music is not the distant love of the text but the unattainability of love. He clearly had a liking for Jeitteles, both as a poet and as a medical man whom he could approach with his many incurable complaints, starting with deafness. We have very little further detail about their connection. Jeitteles graduated in medicine in 1821 and returned to Brünn, where he set up as a general practitioner, achieving near-heroic status during two cholera epidemics in 1831 and 1836. He offered his services for free to two local chairites, one of which was the Institute for the Deaf and Dumb. Might this have been a reflection of his Beethoven connection?

In the revolutionary year 1848 he became editor of the Brünner Zeitung. He died 10 years later, aged 63, and was buried in the Jewish cemetery. Aside from the six poems he wrote for Beethoven, nothing else that he did endures in posterity. Like many of his time and place, Beethoven was sometimes disparaging of Jews, although he had contact with very few. With Jeitteles there is no hint of prejudice, only praise. The fruit of their collaboration is a miniature artform , the song cycle, that Schubert would develop to perfection. There is one other by-product: the idea, that Beethoven held dear, that true art could enable even an outcast like himself to find love.

The six songs in the cycle are almost invariably sung by men; a gender-bending set by Lotte Lehmann, glorious though she sounds, requires a massive suspension of disbelief. They are composed in such a way that one leads seamlessly into the next.

The first question in selecting an interpretation is how the listener feels about Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau. A Lieder singer who covered a large range from low baritone to mid-tenor, he has exquisite diction and limitless gradations of emotion, along with an insatiable ambition to be the very best at anything he attempted. ‘I did too much,’ he said to me sadly in a BBC Lebrecht Interview. This was not full disclosure.

At the peak of his success, F-D used his influence at Deutsche Grammophon to ensure that no-one recorded certain repertoire before he did. The result is that some of his recordings feel a tad formulaic, as if the music was just another box to be ticked in his personal catalogue. Much as I liked and admired him, my conclusion is that Beethoven was not his forte – not in this cycle , at least. Feel free to disagree. Of his three recordings of this set, the first, with Gerald Moore at the piano, is the least mannered.

The purest of German tenors Fritz Wunderlich, with Heinrich Schmidt at the piano, is higher up the scale than Fischer-Dieskau and sunnier in outlook. His singing goes straight to the heart, even if he gives the impression that if he can’t get this beloved there is always be another not far behind. Wunderlich is not the perfect Beethoven man, but by heavens he is beautiful.

Olaf Bär was an East German baritone of brief 1990s ascendancy. He achieves a dark introspection in these songs, coloured even darker by Geoffrey Parsons’ directive pianism. It’s unusual for a pianist to dominate a song cycle quite so explicitly, but the singer seems content to follow. If only for its exploration of the singer-pianist relationship, you should give this set a spin.

Among current interpreters, Christian Gerhaher most resembles Fischer-Dieskau in pitch and precision. He recorded the set in 2012 and I suspect he would have a broader perspective if he did it again. Matthias Goerne in his 2019 DG recording with Jan Lisiecki at the piano is richer in voice, subtler in colour and altogether lovelier to listen to. This is a baritone at the peak of his power lamenting the love that got away. It’s an eternal trope and there is not a dull syllable in it.

‘I did too much,’ said D F-D.

For too long, I would add.

“Like many of his time and place, Beethoven was sometimes disparaging of Jews”

Thanks for stating this.

Quite different from the militant manner in which some people try and modify history, to conform to some political/ideological agenda.

Or as they do in Germany… where they have dedicated hunters who like to discredit people posthumously, swinging that Nazi-guilt-sword at any and everybody.

Fascinating story, yet again truth is more remarkable than fiction.

So Beethoven anti-Semite?

Bode Leary’s comment above was spot on.

Out of which ideological hole did you crawl out?

Using that modern guilt-throw-word, such as you do here, states more about you, than you think.

(Stop poisoning your thinking.)

Swing that sword, again…?

Was Beethoven an anti-Semite?

Not really. He never really thought about it. Anti-Semitism only really became a “thing” much later in the 19th century.

You don’t understand, do you?

Anti-Semitism is a modern guilt-throw-word.

Norman is spot on in stating things the way he does:

“Like many of his time and place, Beethoven was sometimes disparaging of Jews”

(Stop poisoning your thinking.)

I red all his letters. The only statement I have red is that Jews can not cook.

Beethoven was not the kind of guy to be interested in dicrimination etc.

Wunderlich may not be the perfect Beethoven man, but he certainly had the ideal tone for this lovely Liederkreis when he recorded it in 1963.

With his secure legato, his nuanced phrasing, his keen feeling for the text and, above all, his natural buoyancy, Wunderlich constantly reminds us this is the longing, ardent admirer of the distant beloved, and this is Beethoven expressing acceptance of sorrow and loss, rather than suffering and self-pity. It is truly art concealing art, and I for one do not miss the baritone voice one bit while listening to his glorious tenor in this music.

It is as mentioned the first song-cycle. It also differs from most that followed in that each song flows into the next without pause, nd the first is re-capped at the end.

The stand-and-deliver baritone Gerhard Huesch made the first recording I know, with exemplary diction and a fine “Andenken” as the last of four 78-rpm sides, wirh his regular accompanist Hans Udo Mueller. Huesch was Beecham’s Papageno and sang Christus to Karl Erb’s Evangelist in Guenther Ramin’s St. Matthew Passion, along with Dichterliebe and a notable Winterreise and Schoene Muellerin.

I’m grateful for Wunderlich, Baer, and like Gerhaher within reason, Hermann Prey less do, but Goerne not at all. I value Fischer-Dieskau’s perfect diction taste, control, and the beauty of his young voice with Herta Klust. I don’t care for anything Schreier sings.

Lovely to see Olaf Bär included on the list – one of the very finest and too often forgotten these days.

Wierd that he was so quickly forgotten. So happy to hear him again.

There were a number of reasons behind his early – and sudden – disappearance from the concert/opera stage. According to an interview published in July 1998:

‘Bär’s career has had its ups and downs. He had serious vocal trouble in 1990-1991. “Before the age of 30 or 35, one sings with a natural voice. In my thirties I noticed that my voice wasn’t doing what I wanted.” Bär attributes his trouble to an improper technique that placed too much pressure on one part of his vocal cords. “When the problem first surfaced, I developed bad habits trying to compensate, which just made it worse.” He went through a period of re-training that lasted almost two years. “I had to un-learn the bad habits I picked up along the way, and to re-learn how to sing properly,” he explained. Once the physical problems had been corrected, the psychological scars remained. “I would get very nervous singing stuff that had given me trouble before. But with self-knowledge and proper advice, I regained confidence.”

Bär was one of EMI’s most prolific recording artists, participating in 19 recital albums since 1983, but the label recently let Bär’s exclusive contract lapse, blaming the poor sales of his two recent albums of German Christmas songs and lieder by German opera composers. Bär attributes the poor sales to a complete absence of promotion by EMI, and the general downturn in classical music sales. He regrets the cancellation of a planned recording of lieder by Schreker and Marx. “I am not complaining. I had many good years with EMI. But companies should not expect lieder to sell like Bocelli or L’Elisir d’Amore with Alagna and Gheorghiu. Maybe some independent company will be interested in the new projects I have prepared.” Bär laughs at the notion that he makes money from his many recordings. “EMI paid an initial fee for the studio session, but royalties so far have been minuscule. Maybe there will be some for my grandchildren!”‘

Here is the full article:

http://www.scena.org/lsm/sm3-9/sm3-9OlafBar.html

Bär still lives in his home town of Dresden and since 2004 has been a professor at the University of Music in Dresden and leads the Lied class. Most recently he gave a masterclass for singers at the Richard Strauss Festival in Garmisch-Partenkirchen in 2018.

Do not forget two recordings by British greats, viz.:

John Shirley-Quirk, baritone with Martin Isepp, piano and

Martyn Hill, tenor with Christopher Hogwood, fortepiano.

Both very rewarding listening to!

Olaf Baer is only 63. I don’ know if , or why, he has stopped performing. I must look upt Lotte Lehmann’s recording of “An die ferne Geliebte”. I always gain or learn something from her, even if, like Licia Albanesi, she turned breathlessness into an expressive device.

Playwright Franz Grillparzer famously delivered the eulogy at Beethoven’s funeral. He is supposed to have said “Fortunate the man who through his love can make another’s greatness his own, for it is given few men to be great in themselves.”

Song-cycles … Vaughan Williams/ R. L. Stevenson “Songs of Travel”, Georgy Sviridov’s “Petersburg ” cycle and Pushkin songs unforgettable from Dmitri Hvorostovsky, Schubert of course, and Schumann’s “Frauenliebe”, “Dichterliebe” and two Liederkreise, especially the second Op. 39 with a heart-breaking first song so memorable from Suzanne Danco. There just be many others in the later history of the form, but these stand out for me.

The triple-decker “Fetes galante” originating with Watteau’s paintings and French poems (Verlaine?) set by Debussy; Faure’s “Le bonne chanson”, Jaques Ibert’s “Don Quichotte”. Do Ravel’s Greek songs count?

.

Lieberson, Jake Hegge, who else? Carl Loewe wrote magnificent Lieder but no cycle I know of. Mahler splendidly, and best of all Richard Strauss’s “Four Last Songs” that fittingly closed an era or two.

Another poster on the Hoertnagel thread has reminded me that Austrian baritone Wolfgang Holzmair would be ideal in this cycle, and Beethoven’s other songs, and indeed in anything he’s recorded such as Schumann, Schubert, and Austrian folk music.

He first studied and played bassoon, as Wunderlich the horn and Hans Hotter the organ. It did none of them any harm.

Thanks, erudite Music Lover, for all your informations about Olaf Baer’s life and career..