The inconquerable Appassionata

mainWelcome to the 73rd work in the Slipped Disc/Idagio Beethoven Edition

Piano sonata No. 23 in F minor op. 57, ‘Appassionata’ (1804)

Three times as many pianists have recorded the 23rd sonata as those who performed the 22nd. The so-called Appassionata took off in public esteem when a publisher gave it the present title, a decade after Beethoven died. Among its ardent fans was the Bolshevik leader Vladimir Ilyich Lenin, who told Maxim Gorky: ‘I know nothing that is greater than the Appassionata; I would like to listen to it every day. It is marvellous, superhuman music. I always think with pride – perhaps it is naïve of me – what marvellous things humans can do.’

What we know of its composition is that Beethoven dreamed it up while taking daylong walks in the Vienna Woods, near Döbling, in July 1804. His pupil Ferdinand Ries recalled: “We went so far astray that we did not get back to Döbling until nearly 8 o’clock. He had been humming, and more often howling, always up and down, without singing any definite notes. When questioned as to what it was he answered, ‘A theme for the last movement of the sonata has occurred to me.’ When we entered the room he ran to the pianoforte without taking off his hat… He stormed for at least an hour with the beautiful finale of the sonata. Finally he got up, was surprised that I was still there and said, ‘I cannot give you a lesson today, I must do some work’.’

The opening movement contains the arresting motif of the fifth symphony. The central passage throbs with mischief and yearning. The finale is a race through the woods, perhaps a race to the death. In all, it lasts 25 minutes and is full of ever-changing drama. Beethoven keeps hitting the bottom notes on his new Erard, testing the pianoforte almost to destruction. He crams more action into this sonata than, perhaps, any other and pianists seize licence to make of it what they will. Of Beethoven himself, playing this sonata, it was observed that ‘the moment he is seated at the piano he is evidently unconscious that there is anything else in existence.’

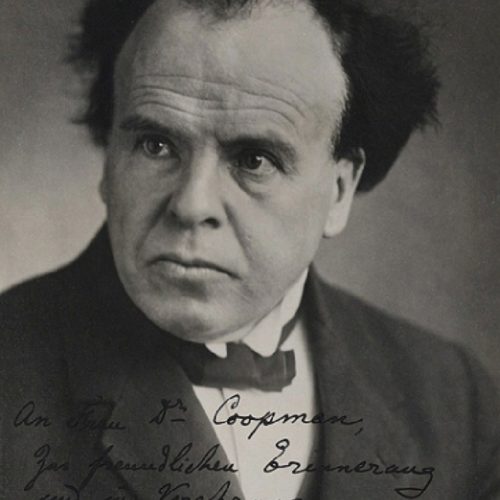

Of all the pianists who addressed this sonata on record, the first looked most like Beethoven, and maybe sound like him, too. Frederic Lamond was a Scotsman who studied with Liszt and may even have played Beethoven’s Broadwood piano, which Liszt kept at his home in Weimar. Lamond was turning 60 when he made this premiere recording of the Appassionata in March 1927 and his handling of the fast parts is not always immaculate. The poetry of his playing in the middle movement is also a trifle mundane. But the physical resemblance and the linear connection through Liszt make this compulsory listening as a benchmark for all that succeed him.

Arthur Schnabel, a full generation younger, knows the meaning of passion and pursues it with a vengeance. The finale is reckless, headlong, madcap, irresistible. Hard to imagine that some disparaged Schnabel as over-analytical. He could improvise his way out of a Houdini knot and this performance stands among his greatest monuments. I still find myself shaking my head in disbelief at the tenth hearing.

No less arresting is Emil Gilels, whom DG commissioned to record the complete sonatas in the 1970s. Temperamentally cautious but possessed of a technique that encompassed unlimited notes at once. Gilels lets the sonata unfold as if by its own volition. What we hear is the unravelling of Beethoven’s pursuit of love – at this time, one of two sisters call von Brunswick, he wasn’t sure which – in the manner in which the composer scribbled it down at his cottage desk. Gilels is another with a head like Beethoven’s and a life of inner turmoil. The recording, made in Berlin’s Jesus-Christus-Kirche is among the clearest and most perfectly balanced of the pre-digital age.

Neither Arthur Rubinstein nor Vladimir Horowitz was a Beethoven specialist and both address the passions of this sonata in ways that defy convention, Rubinstein by thundering away in the lower Steinway regions like a faulty heating system and Horowitz by picking out single notes, holding them to the light and asking us to admire them while he decides what to do next. Both are exemplars of a romantic school of pianism that will always have its admirers. Rudolf Serkin, of a more clinical disposition, dictates a prescriptive remedy for the sonata and brooks no contradiction – least of all among American critics, who consider him definitive. His son, Peter Serkin, is in some ways more appealing for his quizzical, questing approach to the finale and for his daring in taking on his father’s legacy – and besting it.

Among other historical oddities is a 1947 Abbey Road performance by the exiled Russian composer Nikolai Medtner, wayward and bleak but reflective of the way his friend Rachmaninov might have approached this work. I am always fascinated by the Frenchman Yves Nat (1954), an almost forgotten teacher of many fine pianist who played with an elegance that transcended mere accuracy. Elly Ney (1957), a favourite with the Nazi leadership, is undreamingly odious. Wilhelm Kempff (1964), no less of a Nazi lackey, is faultless and full of fantasy.

On my reject pile are the unimgnative Van Cliburn and the madly over-imaginative Glenn Gould, the miscast Lazar Berman and the unsmiling though intermittently exciting Yevgeny Kissin. Yundi Li, the first Chinese winner of the Chopin Competition, is out to set new speed records against his arch-rival Lang Lang.

Among current contenders I listen with unfailing delight to the Argentine Ingrid Fliter, who occupies her own time zone without ever taxing the listener’s patience and delivers glistening tone clusters that melt like snow on the tongue. I find the Appassionata to be one of the summits of Igor Levit’s ever-intriguing cycle and I’m very much taken with an Idagio exclusive – Mikhail Pletnev’s 2018 Verbier recital, notwithstanding ragged sound.

When all’s said and done, however, it’s still Gilels first and last.

Where is Richter?

Novodevichy Cemetery, Moscow, Moscow Federal City, Russia.

As you enter the cemetery, go straight up the central alley, at the first major intersection make a right and then turn left before going through an arch to the “old territory”. Richter’s grave is about 10 meters to the left from the arch, near the wall separating the “new” and “old” territories of the cemetery.

Source: findagrave.com

I have to add four outstanding performances I have heard live: Michelangeli, Leonskaïa, Pires and Pletnev.

Rubinstein’s earliest on vinyl 78s is my touchstone. I saw Richter play it and four others. Nikolai Medtner is striking and does not miss the resemblance to Don Cossack sword-dancing squat-jumps at the very nd of the finale’s coda, but even those Rubinstein plays better. Not a work to hear too often.

en

Rubinstein gets the first Donnerblitzen of the primo just right, is eloquent in the variations that relax the tension, and strikes the note of holy rapture in the finale’s cross-hand minor thirds over the bass’s machinery.

Vinyl 78s??

https://web.library.yale.edu/cataloging/music/historyof78rpms

Does anyone know if there is any contemporary description of how Liszt or Chopin approached interpreting this work? That would be fascinating.

It was fortuitous indeed that Gilels recorded both the ‘Appassionata’ and the ‘Waldstein’ quite early into his tragically incomplete Beethoven cycle, before some individual sonata movements in his hands became a tad sober, less subject to WB Yeats’ ‘the fury and mire of human veins’. The ‘Appassionata’ seems to embody both the end of the classical period and the opening of the Romantic era, where the pianist has to suggest in the headlong rush of the finale, how the notes burst the boundaries of vessel. As for the opening of the sonata, so many pianists seem intent on ‘over-interpreting’ the opening dozen or so bars with tempo changes. It’s bracing to consult a score and see only one ‘poco ritardando’ stipulated in these bars.

In Gilels’ two studio recordings of the Brahms B flat concerto, the first with Reiner from the late 1950s is far more volatile and mercurial than the searching and ruminative version set down with Jochum and the Berlin Phil in the early 1970s, a year or so before his recording of Op.57. Note how the opening bars of this second B flat concerto are way below tempo in Gilels’ hands, making this a de facto introduction. Perhaps Gilels felt romantic works such as the Brahms concerti could take such tempo manipulations, but Gilels’ artistic integrity meant that such liberties were scarce in his Beethoven sonatas. ( He does indulge in some charming rubato for the finale of Op. 90.) Impressively, the opening bars of Op.57 for Gilels’ sound as though he is freely using rubato, when in reality many of these effects come from his superb skill in dynamic shading and shifting chordal weights, without excessive changes in tempo. Such thought seems to pervade every section of Gilels’ ‘Appassionata’.

As I wrote under the article on the ‘Waldstein’, if any admirers of Gilels possess SACD players, they should consider the 2 SACD set that Universal Japan released last month of all 9 Beethoven sonatas that DGG recorded of the incomplete Gilels cycle on analogue tape. On my Esoteric SACD player, these DSD transfers sound much better than all previous CD incarnations. They also capture far more harmonic detail than any of the digitally-recorded companion sonatas.

Incidentally, no article on Appassionata interpretations could be complete without some mention of Richter. Norman Lebrecht in his entry on Op. 2/3 refers to a Richter Carnegie Hall all-Beethoven recital of 23 December 1960. The rendition is stupendous, if anything more overwhelming than Gilels in the coda of the finale. Some years ago Sony released a bunch of Richter Carnegie Hall recordings from his 1960 USA tour. The trouble is that the source of most of these recordings was Carnegie’s own subfusc microphone system. These presumably employed omnidirectional mikes that faithfully captured every bronchial affliction of the front stalls. For the 23 December recital, RCA used their own directional mike setup, in stereo, giving remarkable sound for the period. Readers if possible ought to investigate the 24bit 96kHz transfer of these RCA tapes for the whole concert.

The Op.57/26 sonata coupling on an RCA LP were surely from studio recordings, and not Carnegie Hall live? Discogs website says:

Studio recordings made at Webster Hall in New York, November 29-30, 1960.

Ramesh Nair, found your Yeats lines in “Byzantium”. Should have remembered. Now I will.

“I always think with pride – perhaps it is naïve of me – what marvellous things humans can do.’ Oh, the irony.

In his first recording (1945), Rubinstein played the hell out of it – or perhaps more accurately, played the hell *into* it. It may well be the only performance he ever gave, studio or in concert, that can actually be called scary.

Sol Siegel,– Shake. You hear what I hear in Rubinstein’s 1945 first recording of the “Appassionata”.

Even Bette Davis couldn’t improve on it in that marvelous bad movie..

Ramesh Nair, ten points for W. B. Yeats”s fury and mire, whiich I need to search out as I don’t at once recall it.

A nice essay. But I think you forgot one of the greats: Claudio Arrau. Also, you missed lots of great Italian keyboard giants. Gilels is wonderful but what of Richter?

Didn’t Lenin also say about the Appassionata-‘If I keep listening to it, I won’t finish the revolution. ‘

Too bad he didn’t keep listening to it

The event Lenin listen to Issay Dobrowein playing “Appassionata” made into movie with Rudolf Kerrer playing wonderful this sonata and role of pianist

Apparently my web browser is malfunctioning today: the part of this article discussing notable recordings of Beethoven’s Appassionata Sonata that mentions Sviatoslav Richter’s performance(s) – not least the legendary live account at Carnegie Hall in 1960 – was somehow cut out. 🙂

One of the greatest masters of this work is missing: Sviatoslav Richter. Please hear the frenzy of the Presto-coda in the last movement Allegro ma non troppo, for example as recorded during a public concert at the Moscow Conservatory in June 1960. Out of this world.

How is it possible that Sviatoslav Richter was left off this list? Richter’s Appassionata is one of the all time great recordings of the work, right up there with Gilels and Serkin. In fact, it very well might be the best of all the recordings – it is certainly the most exciting performance on the list.This really must be put right!

Norman, where is Sviataslov? Unbelievable finish to his Orchestra Hall Chicago recital debut with five Beethoven sonatas, subsequently recorded by RCA in 1960. I remember being mesmerized in the audience, realizing I had just witnessed something transformative .

The ‘Appassionata’? There are lots of beautiful, excellent recordings, some listed above, some not, but nobody plays it as Maurizio Pollini, and probably nobody has taken so many risks ‘in concert’ with this sonata as he has.

I was surprised at how far I had to scroll through the comments before finding mention of Pollini. I am listening to his live Appassionata, 3rd mvt, from the 2000’s right now. Pianofortissimo is right, “nobody plays it as Pollini.”

I agree- Gilels made what is probably the greatest recording of this sonata.

However- Richter must be mentioned as well, especially his live 1960 Moscow recording and Arrau’s recording from the 70s is also among the greatest.

What made Emil Gilels’ life one of inner turmoil?

Being suppress by his teacher Genrich Neihaus in order to make S.Richter superiour pianist and constantly belittle EG.

Solomon, yes this is the best !!!!!!!!

Emil Gilels was great Beethoven pianist, sure, but not to mention his compatriot S. Richter as his recording of Appassionata for RCA? That is shame.

This is the piece that said, ‘your only purpose on this earth is to be a pianist and you will play this piece’. I was 7. It was Horowitz’s RCA Victor Red Seal LP. Studying it ten years later with Adele Marcus, who studied it with Artur Schnabel, was the greatest gift of life. It remains the staple of our repertoire and will be so for generations to come. Adele would say, ‘the rests are powerful’ and, ‘last movement, MA NON TROPPO, dear!’ In other words, the speed wasn’t exciting, it was the holding back that kept the heart pumping for the listener. That is when I learned it is about the pulse of the listener that dictates our tempi. Oh, this glorious piece, and the second movement being a rare moment in D-flat Major for Beethoven.

Sviatoslav anyone?…

Not even a mention of Richter?

Backhaus, Arrau ???

Richter, Richter,Richter.

You have missed the greatest of them all – Richter’s towering performance.

I’m sorry I was late again in commenting on your Beethoven posts. I wanted to ask what you think of plain-spoken Appassionata performances that make the music more primal and less like a giant. I was wondering how Brendel’s version and the Andras Schiff version fit in?

Daniel Barenboim is also very good with this. As is “der Bachaus”.

Lazar Berman is also fantastic in this as is Kissin.

Kissin? His live-recording Amsterdam 2016 (DG) ist a disaster!

Heard Kissin live playing Appasionata-worst rendition

I have just listened to all the players and would choose as my top 5:

1) S. Richter (clear winner);

2) E. Gilels (very, very good);

3) C. Arrau (exceptional);

4) L. Berman (has all the skills for this piece);

5) E. Kissen 5) D. Barenboim (a tie)

This piece requires passion and intensity in addition to virtuoso technique. Perhaps that is why out of my top picks (6 with a tie for 5th) 4 are Russians: Richter, Gilels, Berman, and Kissin. 2 others are South American but with German backgrounds: C. Arrau, D. Barenboim.

Can there be a successful version that presents a thinking man’s perspective on the music? Can such an approach engage hearts and minds and connect to listeners? I’m thinking of Brendel, Kovacevich, Schoff, Paul Lewis and Richard Goode.

Alessandro Deljavan playing finale of #23-the most expressive. Revelation!

I am happy to note that I’m not the only SDer to feel that leaving Richter off this list- in fact not putting him at the absolute top- is absurd. His Carnegie Hall debut performance of this sonata was a life-changing experience.

Tatiana Nikolayeva’s version should be added to the list as her use of the pedal opens a new world of possibilities to new generations. Richter’s third movement must be some of the greatest playing of history. And in its whole, I consider Bruno Gelber’s recording as the greatest ever

When I told to my teacher Karl U. Schnabel I want to learn #23 sonata, he told: “Eggrigeous sonata”, also about Haydn sonatas. But Karl S. gave wonderful interpretation teaching it in his masterclass. He compare with images of W.Shakespear “Tempest”. Did Karl S. got negative impression from his father Arthur?

Serried ranks of the Richter Brigae are out in force. I saw him play it, as I mentioned, the last of five Beethoven sonatas in Masonic Auditorium on Nob Hill around 1960. The others included the third and twelfth, which he played particularly well. His Appassionata lived up to its name. I missed Rubinstein’s fine judgement and controlled drama, what I can only think of as his musical rhetoric, which was his strong suit. . Clearly exhausted, Richter played one encore, Chopin’s first etude in C, Op. 10. It was fast, but a mess.

Remembered when Gilels came, before him, to the USA and told his enthusiasts, “Wait until you hear Richter”?

I’ll join the list of Richter advocates–I don’t know if any of his recordings captured it but his performance in Symphony Hall, Boston, in December 1960 was earth-shaking.

You must have an elefant’s memory!

Congratulations! 🙂

NY Mike, yes, vinyl 78s. RCA made some in the mid to late 40s, including Rubinstein’s 1945 Appassionata that Sol Siegel and I like, and Til Eulenspiegel with Koussevitzky and the Boston SO. There were also unbreakable Victor V-discs intnded for armed forces during WWII. Maybe others, but these I had and remmber. Very quiet, amazingly so after acetates, and more vivid than anything until Decca ffrr came along after the war. ffrr is for once not a typo but full frequency range recording.

Is it really necessary to have the gratuitous “Nazi lackey” moniker for Kempff? Why don’t you keep stuff like that for a separate column? Or at least give equal weight to the “child molester” Pletnev? Of course, that’s NOT any more welcome, but I do think pot shots such as this are rather obnoxious. We all know where we stand on these issues without needing a wink and a nod to show that you can put a major artist and flawed human being into the quarantine pile with a two word put down.

Kempff played concerts in Krakow, a short train ride from Auschwitz. That’s not a stain which is easily erased.

Probably the smoke not seen from Kraków rail line. Yes he was perhaps a silly man – finally drafted into the forces, I believe to service army trucks.

In Germany everything short train from WWII concentration camps. Should we accuse every performers?When W.Kempff performed in Krakow?

Thanks to Gaston Frydman for mentioning Tatiana Nikolayeva’s pedaling, which I’ll listen for. Bruno Leonardo Gelber’s Beethoven has many admirers.

I saw Nikolayeva play Shostakovich’s 24 preludes and fugues, Op. 87, in 1990 and talked to her. Her encores were four Bach pieces including one from Art of Fugue, at the request of my Polish friend who brought her flowers. She had just made her U.S. orchestral debut with Jarvi in Detroit, Rachmaninoff fourth concerto dedicated to Medtner.

She died aged 69 a few months later from a stroke on stage in San francisco while playing the long 16th fugue in a cycle I’d considered attending. She recorded all Beethoven sonatas, and DDS Op. 87 four times including once on film.

Rcently I heard Glazunov’s eight preludes and fugues from Stephen Coombs. They may have influenced his old pupil Shostakovich. His classmate Vladimir Sofronitzki recorded one of Glazunov’s and several of Shostakovich’s. Maria Yudina was another of their classmates.

Ashkenazy!

Ramesh Nair’s May 23 post: I know of no mention of Chopin’s playing the Appassionata, which might have been repellant to him. He played Sonata 12 with the variations and funeral march, funeral march, but not much other Beethoven. Liszt undoubtedly played it, but no ontemporry decription comes to mind. Anton Rubinstein ismore likely.

I can’t comment on Gilels, whom I never saw live, and whose records I know only a little … the “Elector” sonatas of Bethoven’s adolescence, for example, which interest me like the three piano quartets composed early in Bonn.

Op. 2/3 i a four-movement sonata whose finale is like a concerto without orchestra, even a full 64 halt and cadenza. I aw Richter play it, with Nos. 12, 23, and two others. I like Michelangeli in Nos. 3 and 12, also Wanda Landoska’s piano-roll of No. 12, anothersurprise. For a complete modern set, I like Paul Lewis, and Francois-Frederic Guy in selections such as his superb first “Hammerklavier”.