Which Maestro wins the Pastoral wars?

mainWelcome to the 59th work in the Slipped Disc/Idagio Beethoven Edition

Symphony No 6, ‘Pastoral’, opus 68 (1808) (part 1)

When I was around ten years old, the Pastoral was the only symphony I heard around the house. It was played by my stepmother on her one-piece gramophone and the recording was the one made by the aged Bruno Walter in 1958 with a pick-up group of Hollywood musicians known as the Columbia Symphony Orchestra, after the label which produced it.

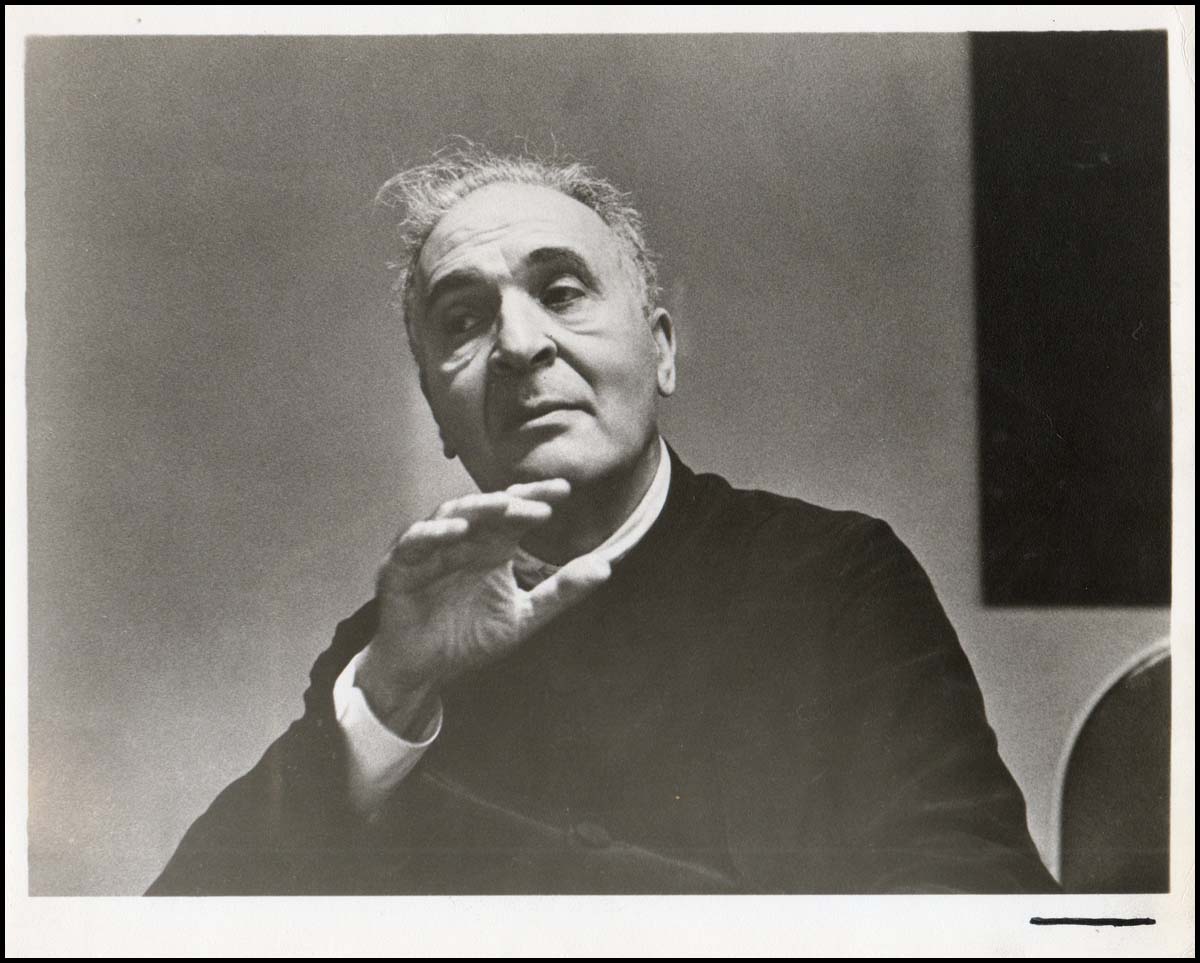

I grew to hate this recording with a passion that fused many elements. My stepmother was a Hitler refugee with emotional disturbances. She had grown up in Munich, taught to revere Bruno Walter as the greatest living conductor, member of a cultural superclass that included his neighbour the novelist Thomas Mann, the composer Hans Pfitzner and the Archbishop of Bavaria, the future Pope Pius XII. Needless to say, I loathed the lot of them with a venom that increased as she played the record time and again until the scratches that crackled through the feeble speakers were louder than the music. Come to think of it, I may even have bought her this odious record for her birthday.

My stepmother’s other obsession was going on country rambles, taking me along in unsuitable shoes. The Pastoral Symphony is all about a country walk in which the heavens open and everyone gets soaked. It was imprinted in my psyche with the worst torments of my late childhood and it resides within that cabinet of personal horrors that I rarely choose to revisit.

Rediscovering symphonic music in my 20s, I attended the Pastoral in performances by other conductors, many as different as could be from the egregious Bruno Walter. I heard Otto Klemperer declare on television ‘Dr Walter is a moralist, I am an immoralist’. Solti, Haitink, Kempe, Boult, each brought redeeming aspects to the performance of a work that I came first grudgingly to admire, then to love.

Later still, as I immersed myself in Gustav Mahler researches, I uncovered some of the less appealing aspects of Walter: that, far from being a moral paragon, he was a furtive Lothario with several mistresses and a fetid home life; that he tried to reach an accommodation with the Nazis before being forced into exile; that, after the War, he exonerated unregenerate Nazis for whom he retained a personal affection. Walter, in other words, was far from being a perfect human being, let alone a shining light.

At the same time he was, with Klemperer, one of the two musicians who were closest to Mahler and I needed to analyse what it was about him that appealed to his mentor. I began listening to Walter’s performances for clues to how Mahler might have conducted. Rather than being conflicted, I found myself becoming gradually reconciled to the all-too-human Walter and respectful of his musical gifts. It was not his fault that my boyhood was blighted by his bloody rain-soaked Pastoral Symphony.

There are three extant recordings of the work by Walter, each set apart from the others. The first, dated Vienna 1936, took me by surprise with wiry pacing, almost breathless in the first movement where the country walk starts. Although the orchestra is the Vienna Philharmonic, with Mahler’s brother-in-law Arnold Rosé in the concertmaster’s seat, there is none of the smarmy soupiness that so often infects its strings, rather an athletic spring to its step. Even the lazy scene by the brook movement has a nervous energy, an intimation of the looming storm. And the nightingale that pops up in the finale anticipates the one who sings in Mahler’s first symphony. In this same year Walter made the first recording of Das Lied von der Erde with the Vienna Philharmonic, in which no Austrian singer would take part for fear of incurring Nazi sanctions.

Walter recorded the symphony a second time in 1946 in the Academy of Music in Philadephia with an orchestra capable of great beauty but unresponsive on the whole to his shimmying shifts of tempo and dynamics. The storm breaks like a Disney cartoon and the finale motors along like a Cadillac on a multi-lane highway. The absence of struggle is a disturbing feature in this reading; perhaps it reflected Walter’s post-War urge to come to terms with his former German identity.

Which brings us to the third recording, the Hollywood one that shadowed my preadolescence and which many critics still mark as their first choice. On my panel, Richard Bratby acknowledges the ‘deep warmth and compassionate, lived-in style from a conductor I find it impossible not to love. Finale has the grandeur and beauty of Parsifal, but with a sweet, lopsided smile.’ I am not sure that I could ever love it the way Richard does but I appreciate the Parsifal analogy for the finale in which Walter exemplifies that panoptic ability of Mahler’s to draw upon the entirety of musical history in the interpretation of a single symphony. This is an outstanding quality of the 1958 performance, although in comparison to Walter’s previous efforts I find it too relaxed, with hints of self-satisfaction. For me, the Vienna 1936 recording is the best of Bruno Walter, its flexibility mirroring his incurable ambiguities.

The antidote to Walter is to be found in Otto Klemperer – particularly in his epic 1957 account with the Philharmonia Orchestra, three minutes longer than Walter in the opening movement yet taut as barbed-wire. Klemperer seizes the Pastoral by the horns, herding it into his field, stripping the brook scenes of sentiment and the peasants’ dance of sentiment. The storm has the suddenness of Shakespearian (or Wagnerian) drama and the nightingale a consoling remoteness. The tension is electrifying and the return of the original theme just before the end feels positively liberating. If this is how Mahler conducted Beethoven, I will take it any day over Bruno Walter’s trademark bonhomie.

More on Pastoral recordings in part 2 here.

Comments