Beethoven: This string quartet could save your life

mainWelcome to the 52nd work in the Slipped Disc/Idagio Beethoven Edition

Beethoven: Razumovsky Quartets, opus 59 (1806)

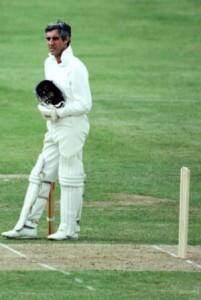

Outside of the boxing ring, there are few ordeals more terrifying in sport than facing a fast bowler in cricket, a man hurling a rock-hard object at you from less than 20 metres and at a speed of ninety-plus miles an hour. At the receiving end, the batsman has time while the bowler is running in to say his prayers while steeling himself for being hit, getting out, or being made to look ridiculous. From the moment the ball leaves the bowler’s hand, the batsman has a fraction of a second to decide what to do. In Test cricket, there is nowhere to hide.

The 1981 series between England and Australia was a brutal encounter between cricket’s oldest rivals. England lost one Test and looked to be heading for a thrashing when, before the third Test, Mike Brearley was appointed captain and everything changed. A philosopher who would retrain as a psychoanalyst, Brearley devised a strategy for dealing with murderous fast bowling. While the bowler was running in, Brearley would hum the opening cello motif of Beethoven’s first Razumovsky Quartet, opus 59/1. Why this particular phrase he never explained, but it worked for the England captain and it works just as well for me, as an aid to concentration and courage in times of great stress.

The triptych of quartets, ordered by the Russian ambassador in Vienna, Count Andreas Razumovsky opens the second phase of Beethoven’s engagement with the string quartet. They are his 6th, 7th and 8th quartets and each of them has a buried Russian tune, the most obvious being the sub-theme of opus 59/2 which pops up in the coronation scene of Musorgsky’s Boris Godunov and in the works of other Russian composers. The Russian flavour, however, is incidental. Beethoven is driving these quartets into new territory, no longer as playthings for high society but as inward-looking reflections on the state of the human race at a time of war, hunger and inhumanity. Opus 59/2 begins with a huge question mark and Beethoven lets the second note hang in the air, as if leaving space for the audience to provide an answer. He seems to have resolved something in his own life at this time: he no longer hides his deafness. Let the world know, he says, what a musician must suffer for his art. Asked by an uncomprehending listener what he was trying to convey in these searching works Beethoven is supposed to have said, ‘Oh, they are not for you, but for a future age.’

Among our panel of expert listeners, two – the violinist Gidon Kremer and the former BBC music chief Roger Wright – make the strongest possible recommendation for the Philips recording by the Quartetto Italiano. You will not have to listen long to be seduced. The quartet, founded by post-grads in Reggio Emilia in 1945, cultivated a warmer, deeper tone than the edgier style of German and American rivals. The players – Paolo Borciani, Elisa Pegreffi (violins, married couple), Piero Farulli (viola) and Franco Rossi (cello) – made their first European tour in 1948. Three years later they had an immersive encounter in Salzburg with Wilhelm Furtwängler, who advised them to loosen up and embrace Romantic freedoms. Two decades later, when they recorded the Beethoven cycle, the quartet had a distinctive sound and an introspective manner that was ideally suited to these middle-period quartets. I am particularly drawn to the way they express Beethoven’s open colloquy with his imagined future audience. There is also an elegance of expression that few others can rival.

The Amadeus Quartet are faultlessly civilised, fearlessly slow, daringly boring at times. One is forever conscious that they are aiming for the ultimate performance and settling for the reliable. I don’t mean to be perjorative – they were a tremendous ensemble and they have much to say in the next group of quartets – but I can’t escape the conclusion that their approach did not quite work in this set.

The Barylli Quartet in 1955 and the Alban Berg Quartet quarter of a century later convey a Viennese sense of ownership in two very different modes. The Baryllis are sweet as apple strudel, the Bergs as reserved as a ticket to the New Year’s Ball. Beyond the ultra-Viennaness of their manner, both are probing, thoughtful groups who never let us forget that deep questions are being asked, whatever they might be.

The American style of the Guarneri Quartet (1967) is decidedly less inquisitve, albeit pinpoint in its perfection. I am more inclined to the swagger of the Emerson Quartet (1997), no holds barred. For the full Russian flavour you need to hear the Moscow-based Beethoven Quartet, close friends of Dmitri Shostakovich, who play for themselves without regard for consumer confidence. It’s rough in patches but refreshing to hear musicians who really don’t give a damn who’s listening, if anyone.

Of all musical genres not has undergone such collective improvement over the past half-century as the string quartet. There are groups today who run rings around the practices of the last century, playing standing up if they please and choosing speeds that would have shattered a metronome of Beethoven’s time. The Berlin-based Artemis Quartet are a byword for high performance and the rising Cuarteto Casals from Spain have a richer range of colours than most and a really slinky way about them in the Adagio. My current favourite is the Parisian Quatuor Ebène (2019) – Pierre Colombet (Violin), Gabriel Le Magadure (Violin), Marie Chilemme (Viola), Raphaël Merlin (Violoncello) – athletic in the most graceful way, like a hundred-metre Olympic runner breasting the tape. It may not be cricket, but it’s great sport.

Comments