Pastoral masters in the Beethoven barn

mainWelcome to the 58th work in the Slipped Disc/Idagio Beethoven Edition

Piano sonata no 15, ‘Pastoral’, opus 28 (1801)

The first work of Beethoven’s that bore the title Pastoral was his 15th piano sonata, published in 1801. The name was given by a London publisher who thought the music sounded like a day out in the country. Beethoven never said whether he liked or disliked that idea. His previous sonata, the Moonlight, had sold like crazy on the brilliance of a publisher’s title. Might this one repeat that feat?

No hopes. The Pastoral Sonata is a broken clothes peg: it was never going to catch on.

To begin, the left hand plays the low note D 24 times in as many bars. Beethoven seems to be simulating the groundbass that late-baroque and early-classical composers like Antonio Vivaldi used in what was called their ‘pastorale’ style, underpinning the music with a reassuring drone. In baroque terms, the ‘pastorale’ designation was more a mood than a location, conveying a gentle, calming composition, nothing to frighten the horses (or their owners). Beethoven’s Pastoral Sonata was intended to reassure amateur piano players that it was within their grasp. More respected than loved, the sonata is hardly ever included with the Moonlight in compilations of favourite piano works. In fact, it has fewer than half as many recordings as the Moonlight and, in the wrong hands (we might mention a few), it can get seriously on your nerves.

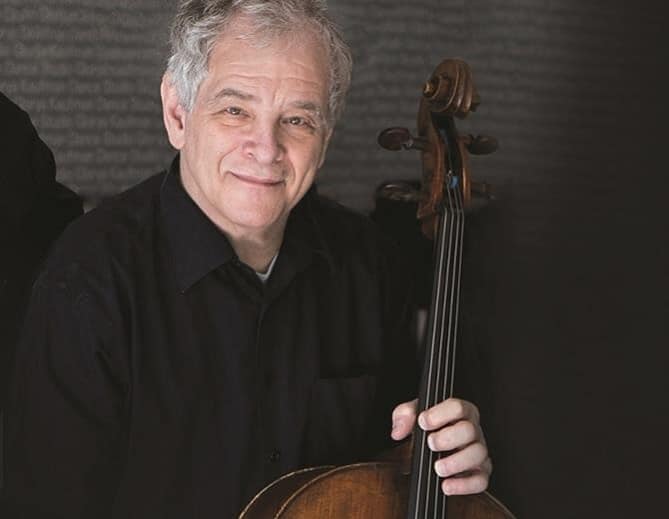

You have only to hear Murray Perahia’s opening bars to know that he was born to play this sonata. A Sephardi New Yorker, from a family that migrated from Salonika, Perahia (the name means ‘God’s flower’) made his breakthrough aged 25 by winning the Leeds International Piano Competition in 1972. He did not look or sound like a winner. There was a deliberate understatement to his playing. In contrast to the crowd-pleasing tactics recommedned for winning, say the Tchaikovsky Competition, Perahia played softly and turned inwards, becoming more and more introspective as the work went on.

In the Pastoral Sonata, he turns the metronomic underpinning of the left hand in the opening movement into an alternative plot, an avenue of exploration in its own right. He treats the andante movement as an anticipation of Chopin’s funeral march, his tempo investing Beethoven’s theme with an uncanny prescience. The scherzo is the least interesting movement, but the finale responds to Perahia’s rare ability to bend a piano line into a shape all his own. This performance was recorded for Sony in 2008, a 60th-birthday year that Perahia dedicated to performing the less-obvious sonatas of Beethonen. Unfortunately, his performing plans were thrown askew by the recurrence of a thumb injury that went on to disrupt the rest of his career. This recording is arguably the best of Perahia and certainly one of the two or three most convincing accounts of the Pastoral Sonata.

Just how great Perahia’s achievement is in this sonata will be grasped by playing Maurizio Pollini’s performance from 1992. An artist of comparable thoughtfulness and self-absorption, Pollini takes a ruminative stroll through the Pastoral without ever suggesting an ulterior purpose to his pleasant perambulation. It’s a perfectly fine interpretation by any standards, except the heights of Perahia.

Glenn Gould plays the second movement more like a tea-dance than a wake; what he’s thinking is anyone’s guess. Alfred Brendel is at his most dogmatic and schoolmasterly. Even Claudio Arrau fails to impart more than the occasional insight. Wilhelm Kempff sanitises the sonata of anything that might be mistaken for powerful emotion. Wilhelm Backhaus will get on your nerves in ten seconds with dogmatic, unyielding phrasing. Paul Badura-Skoda (1987) plays the most clangorous foretepiano; bring on the Nurofen. Mari Kodama (2012) is blandness incarnate. Andras Schiff (2007) uses a modern pian to convey a sense of the baroque ‘pastorale’, refreshingly full of light and brightness. The shortlived Dino Ciani‘s noble attempt to rethink the work is sabotaged by tinny piano sound and one or two audience members who cannot stop coughing their lungs out at the most delicate points.

We must turn to the Russians to find anything on a par with Perahia’s innovation and introspection. Maria Grinberg and Emil Gilels – both discussed earlier in the series – have many questions that elude other interpreters, along with a few answers. Grinberg does the Perahia trick of using the groundbass to evoke a parallel, half-hidden narrative. Unlike Perahia, she turns the slow movement into a prelude to seduction, the pianist testing, teasing, tormenting herself to see if romance might ensue. It’s Chekhovian stuff, and she gets angry towards the end.

Emil Gilels is, for me, the benchmark in Beethoven piano playing and this is one of the summits of the near-complete cycle he made for Deutsche Grammophon in the late 1970s and early 1980s; indeed it appears to be one of his last sessions for the label. Gilels has an imperceptible way about changing your mind as to how a work should sound. There are no overt nudges or tempo shifts. Rather, he allows the listener to discover ulterior meanings in the prefatory groundbass and the apparently morose andante. What those meanings might be are also for the listener to decide. Gilels would never be so presumptuous as to determine an outcome. He just goes about his business of playing the piano with the deftest of touches and a beauty none can surpass. In the andante, he so takes the breath away with beauty that you hardly care what it means. He repeats that feat with such transcendence in the finale that all you want is for this pastoral atmosphere, whatever it might be, to stretch on forever, beyond this world and, please God, the next one, too.

Next there’s the mystery of the Pastoral Symphony.

Coming up tomorrow, and the day after.

Comments